One of the problems with living to the landmark age of 100 is that not many others from your past are still around to join in the revelry. Except for the really famous, the media doesn't note such events. So today we younger old people make up for that neglect with a couple of references to people who have certainly made their contributions during much of the last century.

Last night we purged our telephone list for the first time in several years. There were a few names on the list we could not even remember, and many others we have not contacted in years. Of course, the only way to do that is to dial the number and see what happens. Although the name is alphabetically well down on our list, we decided to call Woody Woodbury, who since we arrived in Florida, has been a popular local comedian who made forays into the national entertainment scene. We used to have lunch with Woody and publicist Jack Drury until Drury's death in 2021. We were happy to hear Woody's mischievous voice, and one of the first things he said was that he was 101 years old.

Woody Woodbury

Many people don't know Woody is still with us, and fewer recall what distinguished him beyond his world of laughter. During World War II, Woody became a Marine Corps pilot and one of his flying mates was baseball great Ted Williams. The pair did not get overseas, but both enjoyed the Marines so much that they stayed in the Reserves when their unit was called up during the Korean War. Years ago, when Williams was in the prime of his legendary career, they flew the Grumman Panther jet in combat, and Woody described their most memorable mission. Ted Williams’ plane was hit. He refused to bail out and instead chose to nurse his smoking craft back to base. Woody landed first and pulled his plane to the side of the runway as Williams, with no hydraulics to lower his wheels pancaked his jet, took a fiery side almost forever and as it stopped and tilted on one wing "that big son of a bitch was out of this plane in seconds.” Williams resumed his baseball, and when he retired, lived in the Florida Keys where he and Woodbury remained friends until Williams' death in 2002

Ted Williams

Another old friend who exceeded 100 is broadcast giant Joe Amaturo, now 102. Joe, a leading philanthropist often to Catholic causes, was one of the first people we wrote about in 1971. He was new in town, and we heard he gave us credit for quick acceptance. Joe is retired, oddly enough, but his son Lawrence runs a chain of radio stations in California.

Joe Amaturo c. 1971

The crash of two planes in the Potomac River near Reagan International Airport revived memories of a similar crash which had a profound effect on South Florida. In January 1982, an Air Florida plane attempting to take off in bad weather from the same airport crashed into the 14th Street Bridge and wound up in the freezing Potomac. The loss of life was 74 passengers and aircrew and several people on the bridge. The accident was the beginning of the end for Air Florida, based in Miami. Aside from the aircrew, the flight was headed to Fort Lauderdale and many of the dead had local connections. Air Florida began as a local airline but had expanded into international service. After a slow start, the airline had several highly profitable years and its future seemed promising. But the investigations blamed the crash on pilot error - trying to take off with icy wings and poor pilot response to the emergency. 78 people, including a few on the bridge, died. Only five people survived. It was devastating publicly and Air Florida bookings took a dive and several years later it went bankrupt and was sold in distress.

Photos such as this ran around the country, dooming Air Florida.

Almost everybody in South Florida knew some of the hundreds of employees based here. Our own connection was a charming young woman fresh out of college who went from working almost free for an obscure local publication to the attractive job of PR Director for Air Florida. It was she who arranged for us to take a very pleasant press trip to Ireland as part of the celebration when Air Florida introduced European flights. Oddly enough, our friend got favorable publicity for the professional way she handled the crisis and went on to build her own PR firm in New York, specializing in crisis management.

A slightly happy ending to a tragic story.

Robert F. Kennedy the younger is a mixed bag. His co-existence with the corrupt Trump organization is an embarrassment to his distinguished family name. On the other hand, he is admired for a career of environmental work, but the jury is decidedly locked when it comes to some of his current very outspoken positions on public health. Many, including some medical people, think he may have a point about vaccines, especially the batteries given to the very young, but think he has taken the cause to dangerous extremes. But there is another topic on which we think he deserves unanimous applause. Two weeks ago, marking the 61st anniversary of the murder of his uncle, President John F. Kennedy, he said he could convince any jury in the country that the CIA was responsible for the crime. He said all the key players traced to South Florida and the Cuban community's intimate involvement with the CIA. He was right on.

If longtime readers of Gold Coast Magazine, and later this blog, think they have heard this story before, they sure have. Since the 1970s, we have been compelled to react every time we hear prominent figures say that there are so many conspiratorial theories that we will never know for sure what happened. And occasionally, but less often than in the past, we read that Lee Harvey Oswald is the accepted killer. The more thoughtful accounts of this profound tragedy usually trace events from the day of the assassination through the Warren Commission, which pinned the blame solely on Oswald, and up through the government committees in the 1970s which concluded that there was a conspiracy but left the public to pick its own favorite killer organization.

That's where we came in and why today we feel a moral duty to engage whenever important commentators such as Robert Kennedy reawaken the public interest. Gaeton Fonzi was a partner in Gold Coast Magazine, so we are among the very few people still standing who had an inside view of Fonzi's 1970s investigations and know the story behind the story the government never fully told. Actually, it was told first in the pages of Gold Coast in 1980, and we will get to that.

Gaeton Fonzi in the 1970s.

Gaeton Fonzi, and almost all the principal figures in his story, have passed. But his work likely influenced Robert Kennedy. Fonzi was one of the first to seriously challenge the Warren Report in the mid-60s. He interviewed Arlen Specter, later a U.S. senator, the man who came up with the "magic bullet" theory needed to explain how Oswald could have acted alone. Fonzi was shocked that Specter could not explain his own theory. Fonzi's piece in Philadelphia magazine, where we both worked at the time, was read by Pennsylvania Senator Richard Schweiker, who a decade later reopened the investigation in the Church Committee, which evolved into the House Select Committee on Assassinations. Schweiker was convinced Oswald was an intelligence operative set up to take the blame. Fonzi was by then in South Florida with Gold Coast, exactly where Schweiker wanted him to probe the CIA connections to the anti-Castro Cubans in Miami.

Fonzi did just that, finding a leader of the anti-Castro movement who inadvertently told Fonzi he had seen Oswald with his CIA handler in Dallas not long before the assassination. After considerable work, Fonzi learned the CIA man was a high-ranking figure who coordinated the anti-Castro effort in Miami. At that point, Fonzi sensed the CIA attempting to sabotage his work, just as it had the Warren Commission years before. The man who headed the probe, a brilliant Philadelphia prosecutor named Richard Sprague, was forced out when he refused to sign a secrecy agreement with the CIA. His successor was a well-meaning organized crime specialist who could not believe the CIA was involved. He directed the investigation toward the Mafia. Fonzi met some interesting mobsters, but it was largely a waste of his time, just as were various bogus tips Fonzi got from people who turned out to be CIA contacts.

David Atlee Phillips was the CIA man Fonzi linked to Lee Harvey Oswald. He unsuccessfully sued Fonzi and the Washingtonian magazine.

The bottom line was that the final report of the House Select Committee on Assassinations, largely written by Fonzi under pressure, did not give his CIA work adequate weight, and hinted that the mob was involved. In short, inconclusive. Disgusted, Fonzi wrote his own version - long articles that first ran in our magazine and the influential Washingtonian magazine. Fonzi spent the next decade expanding his research and finding other sources linking Oswald to the CIA. In 1991, he published "The Last Investigation." It was praised by JFK researchers but generally ignored by major media. Over the years, however, it has grown in stature. Today, it's cited as a landmark work. When Gaeton Fonzi died in 2012, the New York Times ran a featured obit and said the book was among the best of the hundreds written on the assassination. And anybody who read it knows the CIA was involved in both the murder and the years of elaborate cover-ups.

"The Last Investigation" has seen several printings.

On both Fonzi investigations, the Warren Commission in the 1960s and the reopened investigation in the 70s, we watched over the man's shoulder. In fact, much of his work on the Florida project took place in our magazine office. We met most of the people working with him and they all suspected the CIA. We couldn't help but become something of an authority on the authority. Fonzi is not around to endorse Robert Kennedy's very strong indictment of the CIA, so we will do it in his memory.

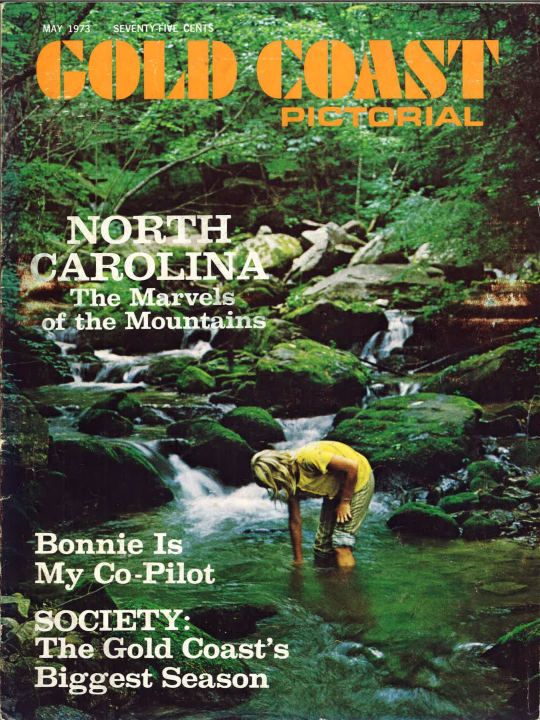

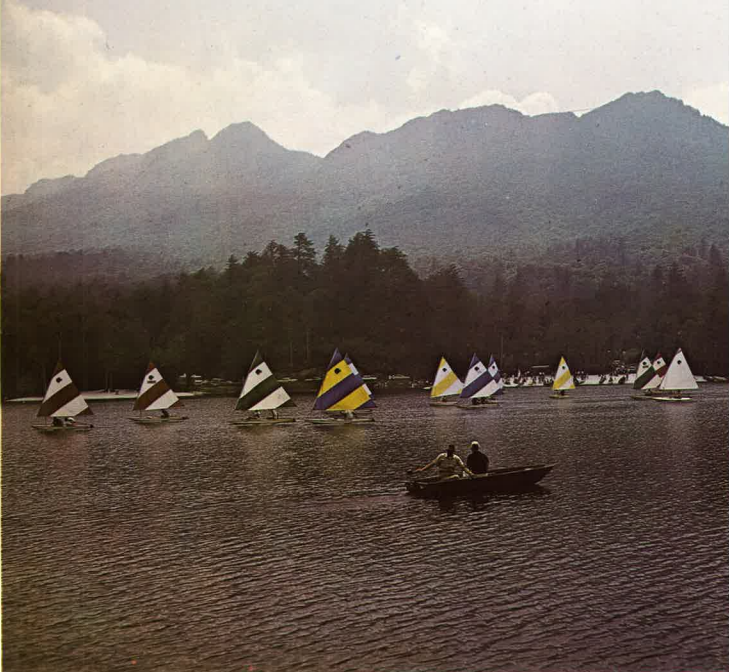

The recent disastrous flooding in the western North Carolina mountains brought back a flood of a happier kind - 40 years of memories of covering the towns and the Floridians who vacationed in them. It began shortly after we arrived in Florida in 1971 to take over what we turned into Gold Coast magazine. We quickly learned that Fort Lauderdale and the nearby towns emptied out in the summer. At least our affluent readers did. And the destination for most was the hills of the Carolinas and north Georgia. It was a logical place for us to follow our audience, and we did not have to go far to get started.

Beginning in the early 1970s, Gold Coast published annual stories about the Carolina mountains and often promoted them on covers.

Just up the street in our Colee Hammock neighborhood in a big walled home lived the Fleming family. Foy Fleming was a community leader, a prominent lawyer and banker. We learned that he took his family, not just in summer but also over the Christmas holidays, to their second home in Cashiers, North Carolina. It has been one of the more popular destinations for Floridians, including the family of former Fort Lauderdale mayor and longtime congressman E. Clay Shaw. We had not yet met Foy Fleming, but we made arrangements to see him in the hills. We got some nice pictures of his family amid their holiday decor. It was the start of regular visits to the area. Hardly a town was mentioned in the recent flood stories that we had not covered over the years.

As we recall, that first story attracted the attention of Betty Mann, who worked in PR for Saks Fifth Avenue. She introduced us to a friend, Helen Tellekamp, from an old Miami family that had frequented Blowing Rock since her childhood. Helen ran a real estate company that operated out of a little office that was noted for its quaintness. We met the next summer and remained friends, and almost annual visitors, over the next four decades. Helen hosted our family on several occasions and introduced us to many friends. They often turned into stories about nearby towns such as Boone, to the north, and even places in the foothills such as Hickory, famous for its furniture stores.

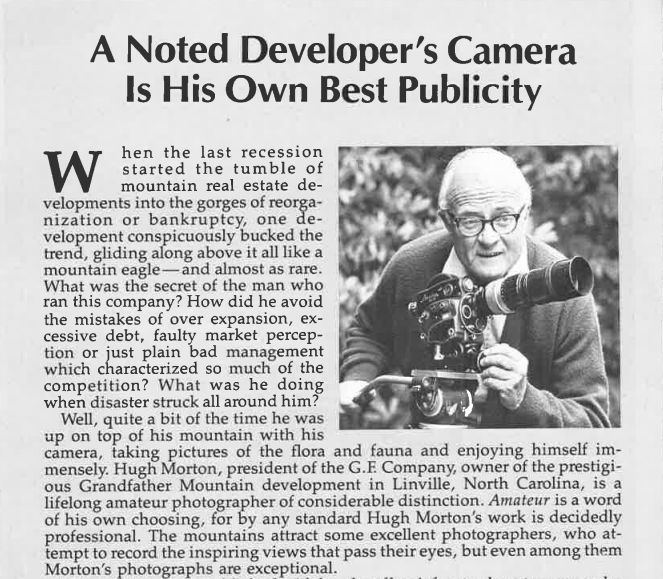

Another place we soon got to know was Highlands, on the western end of the Blue Ridge range. We paid a memorable visit there with Peter Jefferson, a colorful architect out of Stuart. He had a cottage which was charmingly rustic, even by mountain standards. Many of those we covered over the years were full-time mountain people, some of whom had come up from Florida to start businesses. They tended to be in the busier towns, notably Asheville and nearby Hendersonville. One of the more interesting visits was with Hugh Morton, who owned Grandfather Mountain. Morton was wounded as a combat photographer in World War II, and remained in photography for his whole life. He supplied beautiful shots of his mountain and other communities. He was a noted conservationist who made Grandfather a wildlife preserve and protected it from too much development.

The magazine covered Hugh Morton and his Grandfather Mountain in 1980. Morton, a wildlife preservationist, photographed McCormick with one of his pet friends.

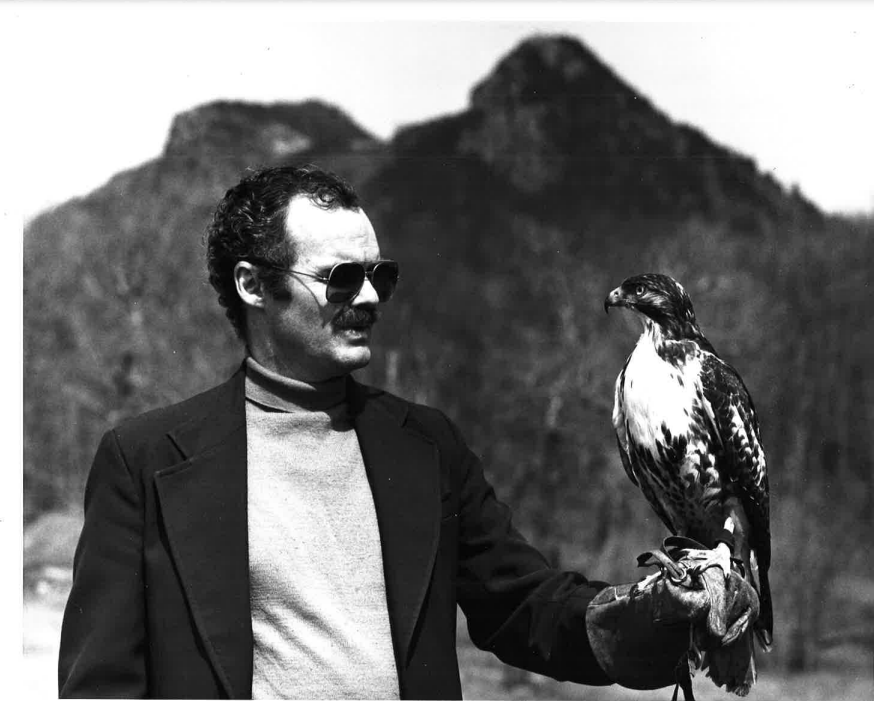

The magazine often featured Hugh Morton's photographs - this one is of his Grandfather Mountain.

As our family grew we joined the crowd who made the hills a cool summer retreat. Our daughter and son-in-law eventually bought a place in Bald Rock, high above it all in Sapphire Valley, near the Cashiers area. After several years, they gave it up for lack of time to use it often.

In the 1990s, a reorganization of our company added a group of new stockholder-directors that would do a major corporation proud. Thanks to our chairman, Bob McCabe, in Vero Beach, we were joined by a member of the leading mountain family. He was a Vanderbilt who was not burdened with that famous name, but his family controlled the Biltmore Estate and much of the surrounding town. That connection led to an advertising relationship with Beverly-Hanks, the biggest real estate firm in the area.

Although our editorial was always legitimate and deserved the special sections we ran in the spring and fall, we valued advertising around the stories. It was tough to determine how effective those ads were, mainly because the advertisers rarely tracked response carefully, but we had a few stories that illustrated our influence.

An amusing one was a wealthy Stuart retiree whose wife wanted to visit Blowing Rock after reading our piece. Her husband wound up buying a classic old hotel in Blowing Rock, complete with the problems of maintaining an old wooden structure. He looked us up through Helen Tellekamp and jokingly blamed us for ruining his carefree Florida retirement.

Another time we dropped in on a young man from Miami who had bought a cozy inn in Blowing Rock. He started to complain that he did not think his advertising in Florida would pay off, when in walked a man carrying a copy of Gold Coast.

“This is a setup!” the owner exclaimed. It wasn’t, but we like to think there were more stories like that which never reached our ears. A lot of memories did however, and we wish for the day the flood disaster recedes and the hills return to the mountain escape we knew so well.

We recently took our first trip north since the COVID pandemic, and we returned to the same form of travel we have taken many times over the last 50 years – the Amtrak Auto Train. And we wonder why this concept, one of the few long-distance rides to make money, has not been duplicated all over the country.

The train takes your car aboard at Sanford, Florida, and terminates at Lorton, Virginia, a short hop south of Washington, D.C. Prices vary according to season but ours cost $1400 each way. There are three classes to choose from – coach seating, a roomette, or a private bedroom. We had the most costly - a bedroom. Sounds expensive, until you consider saving on several tanks of gas and general wear on the car, meals, a night or two in a motel, and the cost of renting a car for 10 days up north.

The Amtrak Auto Train

This concept has had plenty of time to prove its worth. We go back with Auto Train when it was launched in the early 1970s. It was a private venture which was immediately successful. We liked the idea so much that we bought stock in the company. Alas, that did not work out. Buoyed by its quick success, management tried to expand to the midwest. The railroads on that complex route were not up to the standard of the east coast line and management was warned that its equipment was too heavy for the tracks. The result was a derailment, and Auto Train wound up in litigation with its landlord railroads. The losses forced it into bankruptcy.

The idea had proved its potential, however, and newly formed Amtrak decided to revive it in the late 70s. It has been running ever since, making money most years. Currently, it is one of only three Amtrak lines in the black.

We have wondered over the years why this idea has not been adopted all over the country. Considering the millions of cars crowding every interstate, you have to believe that 340 cars a day (about the max for Auto Train) would not choose this relaxed mode of travel.

Most obvious is the midwest route. Certainly, there is plenty of traffic from the Chicago and Michigan areas to Florida. To guarantee success, the auto train could combine with a new conventional service from South Florida, making stops at the Amtrak stations as far as Sanford. From there, connected to an auto train, it would make only major stops - Atlanta, Chatanooga, Nashville, Louisville, and Indianapolis - before reaching a new station south of Chicago. There the conventional train could be detached and complete the route to Chicago and possibly even Milwaukee. Those stops would slow the whole train a bit, but Auto Train users are obviously not in a big hurry.

That may require upgrading some of the rails on that route to handle passenger traffic. Amtrak is already considering a new service from Atlanta to Nashville, through Chattanooga, and along the scenic Tennessee River. That would cover a large part of an Auto Train route.

When that train proved successful, as we believe it would, the new terminal near Chicago could be expanded to provide an auto train on existing Amtrak routes south to New Orleans and west to Los Angeles, the San Francisco area, and Seattle. Again it could combine with regular Amtrak trains serving the busier stations along the way. It would also seem practical on these very long (2,000 miles plus) routes to provide midway terminals to detach and load some of the Auto Train. Denver would be an obvious place on the California Zephyr to Oakland, California.

Those long-distance trains are probably too ambitious at the moment, but the midwest train is not. Indeed it is a concept that should have been continued after the flawed start 50 years ago.

Those who follow public affairs are familiar with public figures being demanded to answer complicated questions in a simple way. Example:

Senator Magpie: "Senator Target, are you directly responsible for all the problems of the world? Just answer yes or no.

Senator Target: Yes or no.

Sen. Magpie: What kind of answer is that?

Sen. Target: You asked me to answer just yes or no. I answered yes or no.

Sen. Magpie: I see, you're being a wise guy. Let me rephrase. Without answering yes or no, just answer yes or no to the question - are you responsible for everything bad in the world.

Sen. Target: Well, you have asked an existential question that requires an existential answer. If you speak existentially, when it comes to the end of the day, and push comes to shove, and it's crunch time for an existential answer, when the rubber hits the road, and it's the last of the ninth, and you come to an existential inflection point, and it's the 11th hour and time is of the essence it's time to get off the dime, and timing is everything, and put up or shut up, and you need a Hail Mary or kick the can down the road, then existentially speaking, the existential bottom line is that it is what it is. Does that answer your question?

Magpie: I don't know. I forget the question. But I have another. What does existential mean?

Target: That's a good question. It’s a word politicians use when they don’t know what to say. It means what it is. Sort of a long way to say the verb to be.

Magpie: What's a werb to be?

Target: It's verb to be. I forgot you're a MAAG. It's kind of existential. like "to be or not to be. That is the question.”

Magpie: Like the Beatles song. They wrote that, right?

Target: If you think existentially, yes or no. And maybe that’s your two-word answer. Until something dumber comes along.

The business section of last Sunday's New York Times had a long article about a Swedish company that is solving its affordable housing need by building modular homes - factory units that are cheap to build and easy to erect. The article said U.S. companies are starting to pick up on the idea as a way of providing the low cost housing that is in such short supply. The problem is serious in South Florida where so many rich people need poor people, often immigrants, legal or non, to maintain them. Alas the poor people can't afford to live anywhere near that work. Thus a shortage of affordable housing.

The Times piece mentioned some U.S. companies entering the modular field, along with some past efforts that for various reasons did not work. We only read the article because it relates to our family's history in a sad way. To our surprise, for a paper that is usually thorough about such history, there was no mention of the largest pre-fab failure of them all; one involving what was once the most powerful retailer in the nation. From early in the 20th century Sears, known as Sears, Roebuck at the time, had a pre-fab housing business that produced 75,000 houses, many of which are still standing and have become something of tourist attractions.

Sears ads showed a variety of homes.

That's where it hits home. Philadelphia was a major Sears employer. Most families in our old neighborhood had someone working for Sears. That's where many couples met, including our parents. Dad went to work in the early 1920s and spent most of the next 21 years in the pre-fab division. He specialized in plumbing and heating, which was one of the big attractions of the program. Depending on how much they wanted to spend, buyers could have a house shipped to a location ready to occupy. Buyers had to put the parts together. Some handy people did it alone, although most had neighbors' help. In a few days, a house would appear.

Sears offered a variety of designs, under a banner of "Modern Homes," from very basic structures to elaborate houses that still look good today. But what had been a thriving business took a downtown in the Great Depression. In order to make it easier to sell houses, Sears had entered the mortgage business, and the depression resulted in many defaulted loans. Sears, with classic bad timing, in the early 1930s moved its Modern Homes unit from Philadelphia to a bigger facility in Port Newark, New Jersey. Dad commuted for several years then moved our young family to North Jersey. He was just in time to see the weakened economy catch up with Sears. Facing big losses, Sears closed the Port Newark operation in 1940. Dad managed a transfer to Elmira, New York, where he managed plumbing and heating in the local store. My mom was never happy away from Philadelphia, and in early 1942, we moved back to Philadelphia. Again just in time for Sears, anticipating a loss of business as we entered World War Two, decided to lay off a bunch of middle management personnel. After 21 years of faithful service, my dad was out of work.

It is difficult to overstate the trauma for a 46-year-old man with three young sons. Dad struggled for a time, then found work in the insurance business. He wasn't cut out for that field. He did not like to gladhand or sell to relatives and friends, but he managed to survive, thanks to the protection of a union. He was always struggling with debt until we got out on our own. But getting canned by Sears permanently scarred him. Before that event, photos showed a confident, almost cocky man. Afterward, he appeared dignified but resigned to having wasted the best years of his life.

A final irony to this story. In hindsight, it appears Sears left the housing business at a very time when it could have been saved. The war produced an urgent demand for new military facilities, hundreds of barracks, and other structures needed for training. Given its experience, those buildings would have been child's play for Sears to produce, and they could be installed by army engineers. By the end of the war. it should have recovered from its pre-war mortgage disaster and be poised to fill the demand for housing from thousands of returning vets starting families.

We wish those companies today entering the modular home field well. Mostly we wish them the one quality that all businesses need. Timing.

If you ignore the God-awful Manhattanizing of downtown Fort Lauderdale, in which he and all other elected officials share discredit, Fort Lauderdale Mayor Dean Trantalis is looking pretty good in there lately.

He has stepped up in the debate over whether a bridge or a tunnel should be built to end the bottleneck where the FEC Railway tracks now cross the New River on an ancient lift bridge. It disrupts busy river traffic which will only get worse as the Brightline expands and other passenger trains are introduced - something that is already happening. Trantalis favors a tunnel and has proposed a shorter, much less expensive design.

Broward County has favored the bridge, which would be enormously disruptive, and as Trantalis has pointed out, be far more expensive than published estimates, which don't include land costs and other construction such as rebuilding the elaborate new Brightline station. Nor does it consider the impact of a high bridge soaring through downtown, impacting new high rises being built near the tracks. The tunnel in contrast will cause little disruption.

More recently Trantalis has taken a position on the very controversial proposal to rebuild La Olas Blvd. in the heart of the business district, which includes removing the median which endows the section with its uniquely welcoming atmosphere.

This painting of Las Olas looking west was done by recent Florida State grad Colin Breslin, no connection to the writer except his grandson.

A little history here for the business community which is pushing for such a dramatic rebuild. Las Olas, of course, is the oldest street in the area. On it sits the first structure, the Stranahan House, now a historic site. The street was also home to the original St. Anthony Church, which likely drew more traffic than any other early structure.

The boulevard evolved slowly. Its modern character began when the elegant Riverside Hotel opened in 1936. A few years later Maus & Hoffman led a movement of fine shops from Northern Michigan to South Florida, most following the men's store to Las Olas, or near it. These events gave Las Olas its commercial character, but the street closed down after dark.

There was no good restaurant until William Maus backed Louis Flematti in opening Le Cafe de Paris in 1962.

Other restaurants came and went over the years, but it wasn't until the late 60s that the median was installed. At the same time, Wells Squier redesigned the heart of the street, with charming facades which make ground floor structures appear bigger, but there was little nightlife or entertainment. The Riverside Hotel had a dark room where the new Maus & Hoffman store now sits which featured good talent on weekends, but the nightlife we know today was still years down the road. Until fairly recent years, Commercial Boulevard, far to the north, was the place to frolic after hours.

That gradually changed during the 1980s. A big step toward the Las Olas we know today came in the late 1980s. Kitty Ryan opened O'Hara's Jazz Club next to the Riverside. It became very popular on weekends and was a hangout for press people, back when there were enough of them to justify a hangout. Its popularity led Ryan to convince the city to allow sidewalk tables. O'Hara's closed to make room for the Riverside Hotel expansion, but by then, other establishments, including the Riverside, were busy with outdoor dining. The whole movement would likely not have been possible without the shaded median that added greatly to the outdoor ambiance, by slowing traffic on the ever-busier boulevard, and made crossing from one side to the other an easy and safe process on new crosswalks.

In 2024, the nightlife has spread west with some good restaurants snuggled under the new office buildings, and traffic in the primary shopping blocks has steadily increased so that sidewalks, with tables, are often overcrowded and creating a safety problem.

From published comments and word of mouth, most residents think removing the median is a bad idea. They think it has much to do with the popularity of the boulevard. Fortunately, so does Mayor Trantalis.

The proposal to eliminate the median points out that the landscaping trees will not last much longer, and instead of replacing them, calls for widening the sidewalks and landscaping them with oak trees. Sounds nice, but will it retain the charm of the median, and will traffic speed increase without the divider, thereby negating the goal of improving pedestrian safety?

Mayor Trantalis has posed a creative solution. Noting that sidewalks on the north side of Las Olas are smaller than the south, he suggests widening only that side to relieve the more serious pedestrian congestion.

There are legitimate opinions on both sides of this issue. The opinion here is that it is risky to change what obviously works, for something that may not.

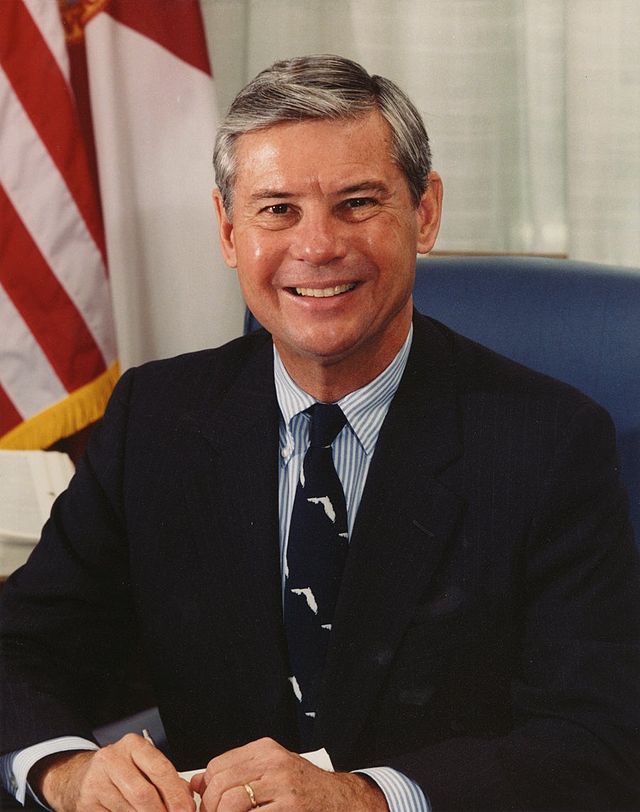

The death of Bob Graham has brought an avalanche of accolades for the kind of political leader they don't make anymore - at least in Florida. We could not help but relate Graham’s passing with circumstances surrounding our first exposure to the man.

Bob Graham, 2001

That was in 1974. We were new to Gold Coast Magazine and slowly adding the types of coverage that the magazine lacked. We did sports when Le Club International sponsored a car in the Grand Prix of Monaco, and then we covered the Miami Dolphins when under new coach Don Shula they gave promise of future success. We did not know much about Florida government except that Claude Kirk had attracted national attention as a flamboyant, often outrageous governor. He had been followed by Reuben Askew, whose notions of good government departed from most of Florida's past. He had a reform coalition composed of men from both political parties.

That first visit to the capital was aided by Broward Countians Ed Trombetta, a Democrat, and Van Poole, a Republican. We did not know it, but we crashed a historic event - the modernization of Florida government with the Government in Sunshine movement. It was led by a relatively young group of legislators including Republicans Joel Gustafson and George Caldwell from Broward and Don Reed from Palm Beach. They joined outstanding representatives from Miami, including Bob Graham.

The standout in that group, however, was not Graham. That distinction belonged to Marshall Harris from Miami. He was called "the Jewish William Buckley." He was Harvard undergrad and law, and he had a patrician bearing and eloquent style like Buckley. And like Buckley, he could be arrogant, but his intellect and hard work made him an admired figure by both parties. He had been named "legislator of the year" three times in the years before we met..

The late Joel Gustafson described Harris at the time.

"He's one of the brightest people I’ve ever worked with. Fiscally, he's very conservative, really tough on the budget. He could almost run as a Republican. Nobody was quicker to take the various departments to task over how they spend their money."

He added thoughts when Harris died in 2009. He had seen him only a few times since both departed Tallahassee. In fact, our phone call was the first time he learned of Harris’ death.

"When I had some issue I wish I could have talked to him. He always worked on it. There was a bond in the people who showed up in those days. We were like a big fraternity."

Can you imagine a prominent GOP legislator describing a Democrat in such terms today?

Unlike Harris, who retired from public life, and whose death was little noted, Bob Graham went on to serve as governor and U.S. senator. Upon his death, we regret that the good work he and men like him and Marshall Harris did in Tallahassee is now being taken apart piece by piece by Governor Ron DeSantis and his lackeys. The last thing they want is the open government in the sunshine so hard won by men like Bob Graham years ago.

"Masters of the Air," the docudrama recalling the remarkable story of the first heavy bomber units to attack the Germans in World War Two, has saluted the pilots and their planes which took terrible losses before ultimately prevailing over the Luftwaffe's formidable defenses. The series, which ends this week, has been extensively promoted on the internet and has generated interest in the airplanes involved. Most prominent are the Boeing B-17 bomber, nicknamed the Flying Fortress, which pioneered dangerous daylight bombing in 1943, and the North American P-51 Mustang, the fighter which was vital in neutralizing the German fighter planes in 1944 and 1945.

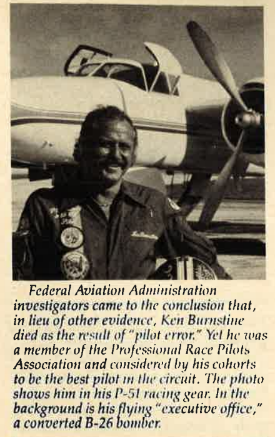

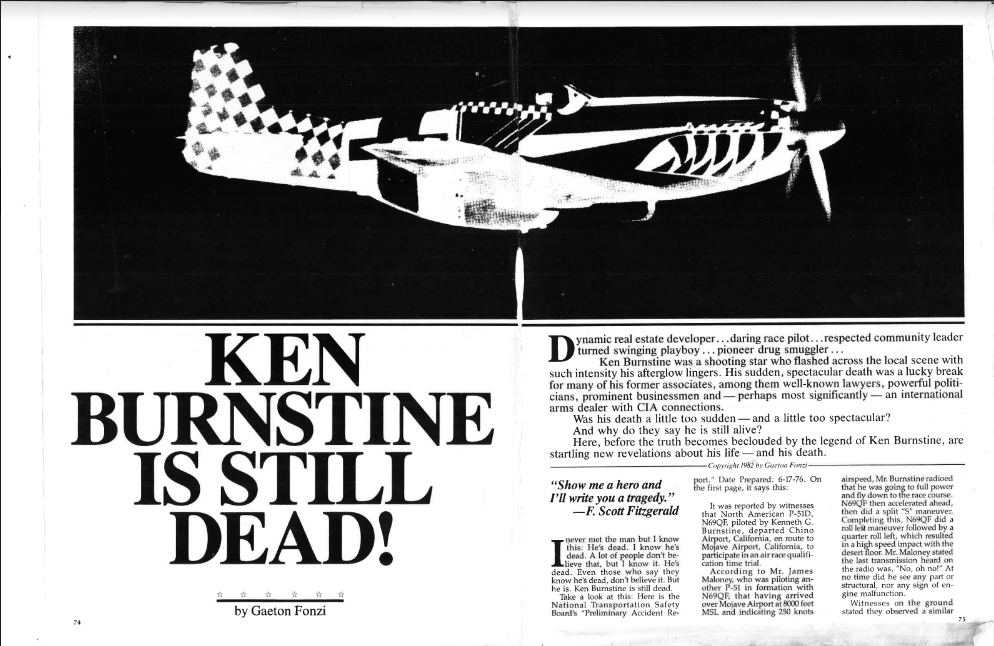

Those two aircrafts, oddly enough, both touched our former magazine, Gold Coast, in curious ways. Covering these tales chronologically, we go back to the 1970s. The P-51 had been preserved in larger numbers than most warbirds, serving for years with several foreign air forces. It also enjoyed a second career as an air racer. A prime example of the Mustang was based in Broward County, owned and raced by a notorious character named Ken Burnstine. Burnstine was an Ivy League-educated developer and accomplished pilot who owned and raced a colorfully painted P-51. He was the essence of flamboyance in his personal life. He gloried in publicity of any kind. Among other attention-getting activities he kept a pet lion in his Coral Ridge home. He also had developed a second career as a drug runner. Planes he owned crashed loaded with dope flown in from the islands and Central America. He always claimed the aircrafts were leased and he had nothing to do with drug running. Nobody believed him, including the police, and people wondered why he was not arrested.

Our magazine helped spread his legend when we featured his P-51 on our cover in 1975 during a general fuel shortage. Margaret Walker, our veteran associate editor, was appalled that we would feature such an unsavory character in a magazine which still was identified with social coverage of people dancing for disease. But the story got a lot of interest, for many of our readers knew Burnstine. But they did not know him long. In 1976, he died when his air racer crashed while practicing for a race in California. The plane burned out and a common reaction was "Oh, that beautiful airplane." Such was Burnstine's reputation that over the next few years, rumors spread that he had faked his death to avoid prosecution for drug running. It was reported that only a thumb was found in the crash and that he had been spotted living the good life in Europe.

At the time, Burnstine had been arrested but was avoiding prosecution by working as an informant for the feds. It was suspected he was running guns south for our government to support covert activities in various countries. In return, he was allowed to keep his drug-running operation on the trip home. That cozy arrangement was about to end, however, for Burnstine had implicated a number of local people, some prominent, in funding his drug operation. The government was about to move when their star witness died in the crash.

All this intrigued Gaeton Fonzi, our partner who had an instinct for stories behind the story. In 1981, he contacted California authorities and learned they were puzzled by all the rumors of Burnstine surviving the crash. His whole body was found in the wreckage, not just a thumb. Fonzi also learned that people at the airfield where he died found the circumstances of the crash suspicious. Burnstine was known to indulge his show-off tendencies upon takeoff by rolling his plane as soon as he gained enough altitude. When he did so that day, he cried out suddenly and his plane plunged out of control into the ground. Observers thought something happened in the cockpit to cause him to lose control. One theory was that a motion-activated bomb went off as soon as he started his maneuver. That bomb would burn out and leave no trace behind. His plane had been untended the night before and someone could have planted the bomb without being seen. In short, Fonzi concluded, he might have been murdered. There were certainly enough people who would want him dead before he could testify against them. At the least, Fonzi put to bed the nonsense about Burnstine living the good life in Europe.

Gaeton Fonzi's investigation led to a three-part series in 1981. It was one of the best-read stories in the magazine's history.

Our encounter with the B-17 came much later. In 2005, we got an invitation to take a press ride on a touring B-17. We accepted, of course, and took a brief (about 10 minutes) hop from Stuart to Vero Beach. We got to tour the plane. Our best memory is before takeoff we sat near the tail and watched Ernest "Mac" McCauley operate the tail wheel manually. A young woman was at the controls that day and McCauley seemed disturbed. "That girl will wreck this plane," he muttered. McCauley himself was the usual pilot, and with years on the job, was called the most experienced B-17 jockey in the world. It is beyond irony therefore that in 2019 the same plane crashed during a demonstration at Bradley International Airport in Connecticut. An engine failed on takeoff, and the plane did not make the runway when trying to return. Seven of 13 aboard died in a crash landing, including the pilot. An investigation blamed pilot error for the tragedy. The plane lost speed on its landing approach because the wheels were lowered too soon and created drag. The pilot was Mac McCauley, the most experienced B-17 pilot in the world.

The magazine did several stories on wealthy owners of vintage planes. Eight-year-old Mark McCormick and his father Bernard posed with this P-51 in Miami in 1974.

The remains of the B-17 the author flew in 13 years before this crash in Connecticut.