The Truth Squad—From the Civil War to Iwo Jima

Recall the scene from “Gone with the Wind” when an older couple sees the names of their sons listed among the dead following a big Civil War battle? The posting of the dead and wounded in such public places as train stations was common in the Civil War because that’s where the telegraph offices were located. It was one of the more realistic touches in a film that had its share of romantic license. The newspapers picked up their information on casualties that way, or from dispatches from their own correspondents posted with most units.

We learned that some years back when visiting the national archives to try and get information on our Gallagher ancestors, John and James. They were our great grandmother’s younger brothers, and the family history says simply that they died in the Civil War. No dates or battle information has come down. We think they lived near Easton, Pennsylvania, for that is where their sister was married in 1854. Census records show two young Gallagher men with the right names living in an Irish shantytown along the Lehigh River in 1860. Are they our boys? We will likely never know. There were 120 men in the Civil War from Pennsylvania with the names John or James Gallagher.

At the archives we discovered that aside from unit records, such as payroll, pension and discharge papers, little information about the average soldier existed. There were no home addresses, next of kin, etc. We asked a worker at the archives how the government notified families when men were killed. He said the government did not. Newspapers, which were with the units in battle, sent that sad information home. Unless a family saved such materials or kept letters from soldiers or their friends, many of those lost in battle were gone with the wind.

But the face of battle has changed.

Witness the recent deaths of a Florida soldier and three comrades in Niger. It led to a controversy over President Trump’s condolence message to the wife of the Florida man. There have been demands for information on the circumstances of his death—looking for someone to blame. The government is right to be cautious in revealing that kind of stuff about what is obviously a sensitive and necessarily guarded anti-terror mission.

The young widow complained that she was not permitted to see her husband’s body. There is a good reason for that. We have previously written about covering a Vietnam funeral when we were able to sit in on the instruction class at Dover Air Force base for soldiers assigned to escort bodies home for funerals. The escorts were told that if a body were listed as “non-viewable” it meant exactly that. They were told that there were women in mental institutions because they insisted on seeing a body of a husband or son disfigured beyond recognition. If the family insisted on opening the casket, the escorts were told to leave the room.

Such has been the intensity of the focus on the recent deaths that some have wondered if the Florida soldier could have been killed by friendly fire. That stems from the case of former pro football player Pat Tillman who was killed in Afghanistan. It was not initially revealed that he was probably killed by our own troops—as if that is some kind of crime. Hardly. Men have killed comrades in the fog of battle since wars began. A notable case was Gen. Thomas (Stonewall) Jackson, fatally wounded in the dark by a Confederate sentry during the battle of Chancellorsville in 1863. Such friendly fire deaths are rarely documented, and sometimes it takes years. In a case in our family, it was about 70 years before we learned that our cousin, Lt. Thomas McCormick, a Navy pilot who died at Iwo Jima in 1945, was likely such a victim.

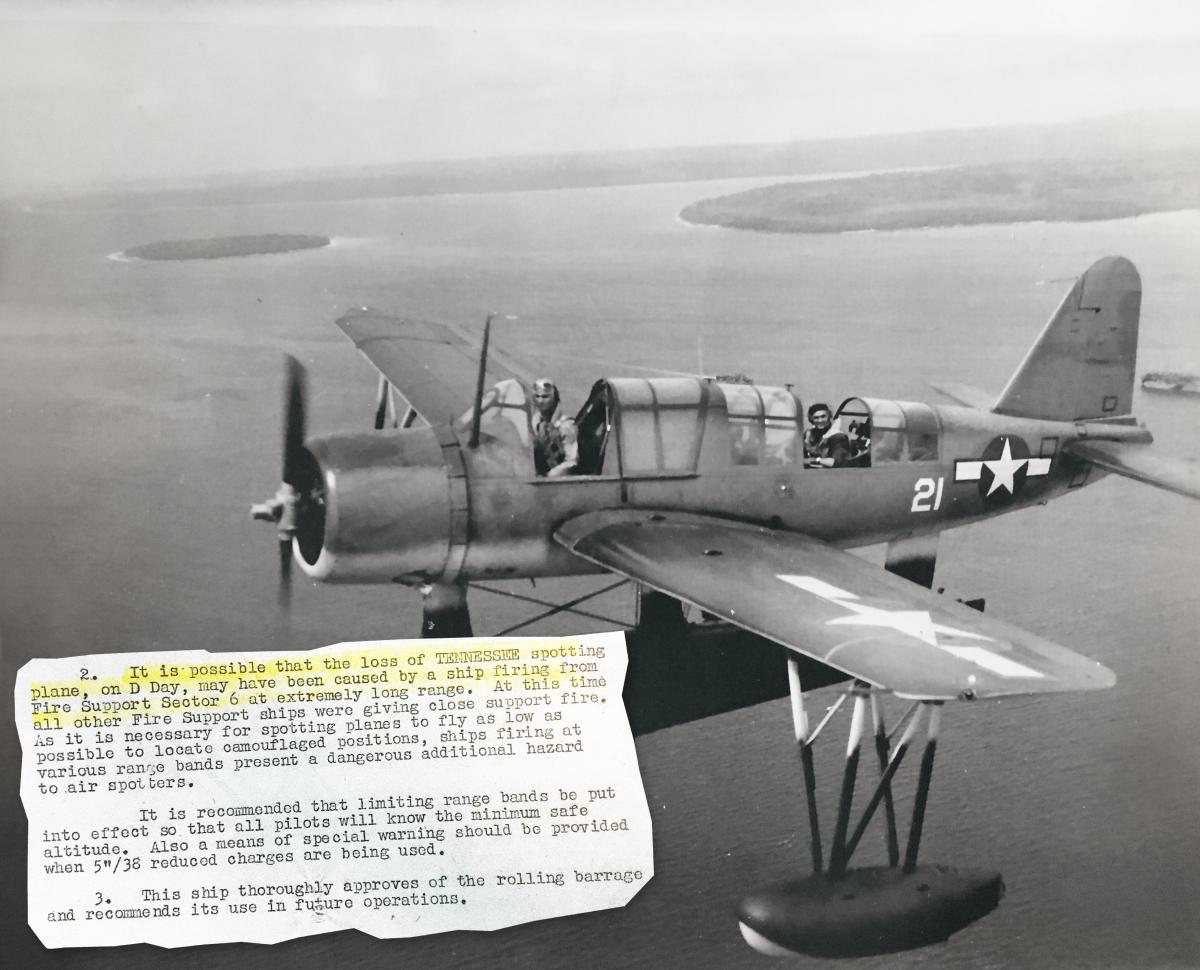

We learned that in the strangest way. As far as we know, Tommy’s mother in Atlantic City (his parents were separated) received only the usual “missing in action” telegram. We don’t think his commanding officer, or any friend, ever contacted her with more information, which usually happened in World War II. Tommy flew the OS2U Kingfisher, a floatplane launched by catapult from the battleship Tennessee. His job was to fly at low altitude to observe fire for the ship’s big guns, which were supporting the Marines’ landing. The ship’s log, which we did not check out until years later, noted that his plane was seen crashing with its tail section missing. There was no explosion in the air or enemy planes that could have shot it down.

A few years ago we contacted Paul Dawson, who runs the U.S.S. Tennessee Museum in Huntsville, Tennessee. To our amazement he knew who Tommy McCormick was and had photos of him in his aircraft (above). It turns out Dawson’s father had been the ship’s photographer, and he saved photos of the handful of pilots on the battleship. He knew them because he sometimes did aerial photos from their planes. Knowing of our interest, Paul Dawson subsequently discovered information that cast light on Tommy McCormick’s last flight.

He discovered an after-battle report marked “confidential,” which human eyes had probably not seen for seven decades. It was secret at the time for obvious reasons, for it told what had gone right and wrong aboard the ship at Iwo Jima.

The report said that a “projectile” had been seen striking Tommy’s aircraft, breaking it in two without exploding. Then, in the closing summary came this revelation: It was possible Tommy’s plane was hit by a large shell from one of our own ships firing at a higher angle than expected. It would have gone through the small plane flying at low altitude without exploding.

From what we know of the military, if the Navy suspected that friendly fire downed the plane, it probably was pretty sure that’s what happened.

Such is the fog of war, even on a clear day in February 1945.