Sears–Once All In The Family

The business pages recently have carried stories about what appears to be the slow expiration of Sears. Some reports describe the demise of the once iconic retailer as almost a death in the family. For our family, that is close to home. Both parents worked for what was then called Sears, Roebuck & Co. in Philadelphia. In fact, that’s where they met.

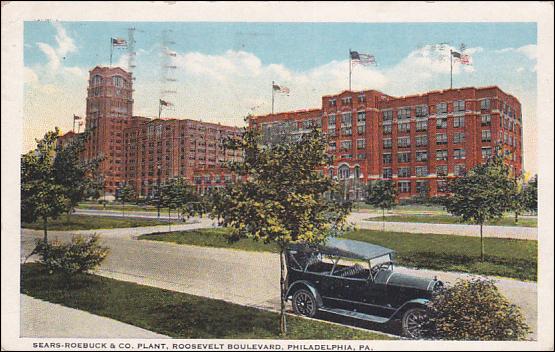

Richard Sears, who sold watches in his spare time working at a desk job in a railroad station, founded Sears in the late 1800s in the Midwest. He soon sold everything else, and much of it far from his Chicago base. In Philadelphia, Sears once had a huge presence. It had an enormous building off Roosevelt Boulevard, which is U.S. Highway 1 in that city. It looked more like an aircraft factory than an office building and had a 14-story clock tower. It was built as an outlet store and plant when Sears was in its heyday with a mail order business that foreshadowed today’s Amazon operation.

The building (above) opened in 1920, and dad and mother went to work there soon after. They were among the first of thousands employed at that site for 70 years. Dad apparently worked in plumbing and heating from his earliest days with the company. Today you would add air conditioning to that field. Mother, just out of high school, was with an advertising unit. One of her tasks was translating letters from French. And she could barely read French. Our parents’ closest friendships were made there, and numerous of our boyhood friends had relatives in the Sears family. It was a great place to work, very progressive for its time. It had a profit sharing program, which enabled many employees of that era to retire with small fortunes in Sears stock.

The Depression, so hard on many families, was barely felt by our family. Dad, who never finished high school, moved up the Sears management ladder and in the 1930s was transferred to Port Newark, New Jersey, where Sears had one of its production facilities for its Modern Homes division. It had started in the prefabricated housing business at the turn of the century and sold 70,000 houses in many designs, some of them pretty fancy. They were built in two plants (the one in Port Newark took up 40 acres) and shipped the raw material for houses by rail around the country, where local carpenters put them together. More than a few were constructed by their owners. Those houses today are prized. People actually search the country to see them. Dad’s background with Sears suggests he handled the plumbing aspect of the home building operation. Buyers could pick their kitchen and bathroom designs; it all came with the package.

Dad started when the Modern Homes unit was strong in the late 1920s. He commuted to North Jersey from Philadelphia for several years, then married and moved our family to North Caldwell, New Jersey. It was just in time to see the Depression catch up with the housing market. Home building slowed and Sears decided to shut down its modular home unit. Dad managed to stay with Sears, but in 1939 it entailed a move to Elmira, New York, where he managed that store’s plumbing and heating department. I gather he did well. I recall mother took us outside to see if we could catch a glimpse of his airplane flying overhead to Washington, D.C. where he received some kind of company award.

Elmira was a pleasant little town, famous as one of Mark Twain's haunts, but mother missed her big family in Philadelphia. We lived near the Chemung River, which had a habit of flooding. Two exciting things happened in the three years we lived there. At age 4 a horse nearly rolled over on me because I was so small the beast did not know anyone was on him. That ended my equestrian lessons in a hurry. The other event was war. The country was still in shock from Pearl Harbor at the beginning of 1942 when dad managed to engineer a transfer back to the big facility on Roosevelt Boulevard—and almost immediately got fired.

As he told the story, Sears calculated that the war would kill its retail business, and decided to cut back on middle management. As it turned out, so many men entered the service that workers were in short supply. Thousands of women filled their jobs.

Dad said the man tasked with firing people was a fellow he had known years before.

“I didn’t like him and never took pains to conceal it,” dad said later in life. “It cost me my job.” He was 46 years old with three young kids and a new mortgage, and after 21 years with Sears, he was on the street. Unfortunately, he had not taken advantage of Sears’ attractive profit sharing program, so he had little backup. A recent article quoted a manager at a Sears store in Georgia who lost his job when his store closed: “But after working there all of those years and then losing my job, it hurts. I’ve taken a big emotional hit from this.”

That statement could have come from dad. Photos of him from the 1930s show a jaunty, almost cocky looking guy in a derby hat. But after losing his job, pictures show a more subdued, resigned man. He managed to get work with a big insurance company and stayed with them until he retired. He knew the value of life insurance; he just didn’t enjoy selling it. When I was 19 he suggested I get a little policy, but then called in one of the young men in his office to write it up.

Our family never took it out on Sears. Over the years we bought appliances from our local store and what little hardware we needed. And their post-Christmas sales were a good way to pick up toy trains at a big discount. Sears did a major catalog business. Even the houses they built could be ordered by mail. But our only experience with it was memorable, and not in a good way.

Our first year in Florida we ordered Christmas presents for the kids through the catalog. My wife had thoughtfully chosen a bunch of stuff, and it was all supposed to arrive a few days before Christmas. For reasons still unknown, it did not. Christmas Eve found us in Smith’s Drugs, which used to be in Fort Lauderdale’s Gateway Shopping Center, trying to get something, anything, for three small kids. Smith’s was a surprisingly well-stocked store, and within an hour we had all sorts of items, from toys to stocking stuffers. The kids never knew the difference. But maybe we should have sensed it was the beginning of the end for Sears.

Over the next decades, Sears remained the obvious first choice for many things. We got tools on a regular basis and a variety of household items, but one by one things you used to find began to disappear, along with other customers. The last major purchase was a refrigerator, but that was at least 15 years ago. We still used their auto store for tires and repairs, but had no need for much else. There were no trains on sale after Christmas.

It is ironic that a company, which invented the mail order business, is among the many retailers being undercut by the modern application of the same idea. It is further ironic that a company that started selling watches still has at least one local customer that likes its inexpensive wristwatch bands. We buy one every couple of years. That probably won’t keep Sears afloat.

Image via