The Coach and his No-Name Doctor

We recently wrote about our first brief meeting with Don Shula. It was 1971 and in just two seasons he had turned the Miami Dolphins from a below-average team into one with a shot at the Super Bowl. We followed his team late in that season, basically the same players who a year later became a team of legend. Its 17-0 record is the only undefeated team in NFL history.

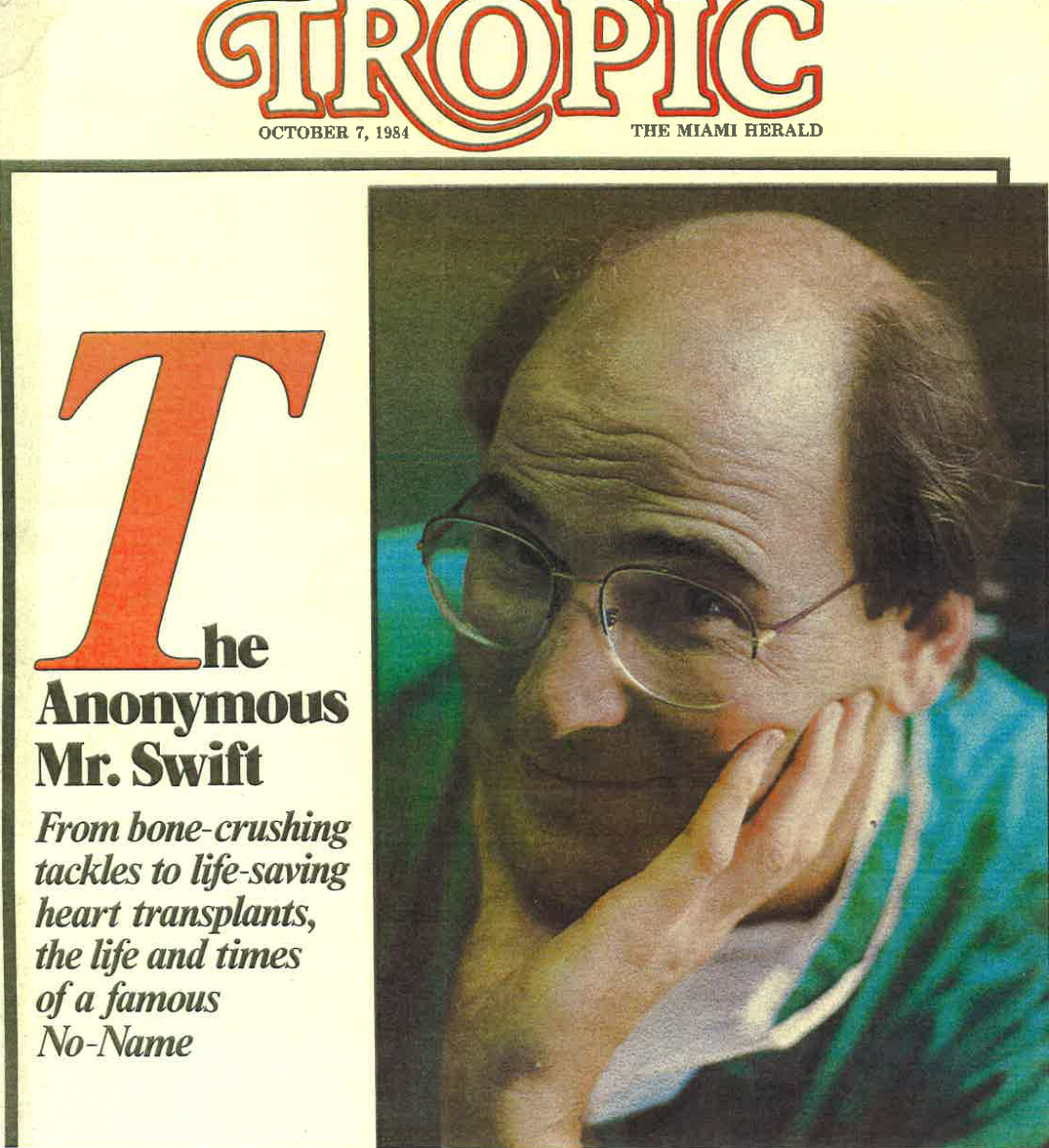

The article was not memorable, except for an iconic photograph taken on a cold December Sunday in New England. It showed a young Don Shula leading his team of destiny on the field. That story, however, led to a more interesting interview with the legendary coach years later. We had gotten to casually know one of the Dolphins' young players, perhaps the least known of the famous "No Name Defense." That was Doug Swift who had an interesting profile written about him by a young writer for our magazine.

Swift was a freak in pro football. He had attended Amherst, a western Massachusetts school known as one of the "Little Ivies." It was academically distinguished, and its sports programs rarely made national news. It was the kind of school where a top athlete might be an art major, which Doug Swift was. Swift did not think he was pro caliber and only thought about playing pro football after his coach suggested it, and the Dallas Cowboys sent a scout to check him out. He first tried out in Canada, was cut, but gained some confidence about his ability to play for money. He followed up when it was suggested he take a shot at the Miami Dolphins, who were rebuilding under a new coaching staff.

He caught an immediate break. There was a players strike and only rookies were in camp. Swift was quickly noticed. He had long hair and a mustache, not unusual today, but a contrast to the mostly close-cropped young players on that era. The late Nick Buoniconti, the recognized leader of the Dolphins' soon to be famous defense, recalled his first impression: ' I saw this big, gangling guy who looked like he should be teaching college somewhere. But as soon as he lined up on defense it was obvious he could play. I didn't know where they'd use him but I knew they'd find a spot for him."

Years later Swift reflected on that camp: "Things went well in Miami right from the beginning. I felt they liked me. I was easy to coach, and it wasn't a very good rookie group that year. Also, I could read. I think they liked me because I could read."

That type of line was common with Swift. He often spoke irreverently of the game he played so earnestly. Just three years into his pro career, he gave an interview to our magazine that was filled with amusing observations that you didn't hear from other players. Samples:

"Sometimes, even when you're not groggy, you wonder what the hell you are doing out there. You're at the bottom of a pile, and you're dressed in all that armor, the pads and the helmet, and you're sweating your ass off and you look down at that artificial grass, man, and you wonder what the hell it's all about. It sometimes seems like the pyramid thing, you know. You start thinking about that. Maybe you're just building a pyramid for somebody. It's kind of demeaning."

He resented politicians, notably President Richard Nixon, sticking their nose into the game. Also lengthy pre-game prayers.

"The bullshit that takes place on the field before the game is ridiculous. You are ready to go and then you have to go through that bullshit. It's like a bad joke. There's no need for those prayers, those invocations."

If that makes him sound bitter, Doug Swift was hardly that. He was a friendly guy, a good locker room presence, liked by his teammates. He laughed easily and his normal expression was a near smile.

But his irreverent quotes suggest that Doug Swift early on realized he had made it in football and now it was time to think about a lifetime vocation. He quit football after six years and entered the University of Pennsylvania medical school. Little was heard about him, at least from our perspective, until April 1984. We happened to be in Philadelphia and noticed a short item in a paper that a team of Temple University doctors had performed the first heart transplant in the history of Philadelphia. It noted that one of the doctors was a former pro football player, Dr. Doug Swift. To be part of such an elite surgical team was a remarkable achievement for a man just four years out of medical school. It was on a par with his football success - a rare case of an undrafted walk on becoming a starter on a good team in his first season.

We figured that story would have played big in South Florida; 12 years after their feat, the '72 Dolphins were ascending into legend. But nobody even seemed to know what happened to Doug Swift. We got an assignment from Tropic, the Miami Herald's Sunday magazine, to do the story. That story led to our second interview with Don Shula, but first the Dr. Doug Swift story. It proved to be infinitely more interesting than our first story on the Dolphins, when we followed that promising team for the last part of the 1971 season.

Dr. Swift remembered us from Florida and could not have been more gracious and helpful. We had lunch, with his beautiful wife Julie along. In response to our questions about his work, he invited us to watch open-heart surgery. We figured that would take 10 miles of paperwork and releases to set up. But he did not bother with the PR stuff. He just said to meet him at the corner where the surgical team entered the hospital. We dressed in scrubs and Swift introduced us to the men and women on his team with simply, "Fellas, this is my friend Bernie up from Florida to watch us work."

The next five hours were the easiest story we ever wrote. Dr Swift wrote it, with vivid explanations of everything he did as an anesthesiologist and quotes during various stages of the procedure. The surgery was a double by-pass of a middle-aged man, and it went perfectly We even got to take a quick look at a beating heart when the man's chest was still open. Not many writers have gotten such a front-row view of a delicate operation, especially not 35 years ago.

We learned that his job was in some ways more complicated than that of the knife-wielding surgeons. He met with the patient first and stayed with him after the operation, assuring he recovered from the very heavy drugs he had been under. Dr. Swift had to be part psychologist, keeping a patient relaxed as he put him to sleep. We watched him make small talk with the patient.

"The banter is important," he explained "It helps determine the anxiety level of the patient and relax it, as well as your own. If they recognize your name and want to talk football, that's fine. Anything to get their mind off what's going on."

The entertaining part of his personality that made him fun for his football teammates was apparent with his fellow physicians. Several times during the operation he made asides which caused their surgical masks to vibrate with obscured laughter. He also made an occasional reference to football. He spoke of the importance of double-checking equipment lined up for the surgery.

"I'm compulsive about this stuff," he said. "Arnsparger made me compulsive." The reference was to Bill Arnsparger, who coached the Dolphins' acclaimed defense of that era.

After that operation, the story was basically ready to go. There remained only to bring it back to South Florida, and that proved easy. Both Nick Buoniconti and Coach Shula not only were willing to talk about Swift, they appeared pleased to do so.

"Doug and his wife Julie really did listen to a different drummer," said Buoniconti, recalling how Swift and travel roommate Garo Yepremian always had healthy foods and fruits in their room. "Actually I love Doug Swift," he added, "He was just unique. Actually there were a bunch of unique people on that team which is what I think made us successful."

Shula recalled how much he enjoyed dealing with Julie Swift, who had gone to law school at the University of Miami and served as her husband's agent. He was not surprised at Swift's medical success.

"I knew he had medical school in the back of his mind," said Shula. "It was just a question of how long he would stay before he got on with the rest of his life." Shula even gave Swift, in his last season, permission to travel a day ahead of the team to take a medical school exam in Boston.

So where is Dr. Doug today.? Good question. He did come to a 10th reunion of the undefeated team and attended the 2013 ceremony when President Obama honored the team at a White House reception. He was extensively quoted in a 2016 piece written by another doctor. Attempts to contact him through the Dolphins were futile. We checked to see if he was mentioned in Shula obits in the Philadelphia papers. Several local coaches were quoted, but no former players. There are several listings for his practice on the internet, but the only phone that worked referred us to Pennsylvania Hospital. The young man who responded said he had no Douglas Swift on his physicians list. It did not help when we mentioned we were looking for a man who had played on the only undefeated team in pro football history. The name did not ring a bell with the young fellow.

Sic transit gloria mundi.

Doug Swift

This Comment had been Posted by Eddy Bresnitz

Great story about a talented physician who I worked with in the early 80s when we were both in training at Pennsylvania Hospital in Philly. The nicest guy, smart with interesting football stories as we took care of hospitalized patients.

Doug Swift

This Comment had been Posted by Scott Johnston

Loved the article. My name is Scott Johnston and I am a longtime TV sports producer trying to track down Douglas Swift who graduated from Amherst I believe in 1970… maybe 1969… He went on to play for the Miami Dolphins for 6 seasons, winning two Super Bowls… If you have a way of putting me in touch with Dr. Swift I would greatly appreciate it. We are doing a podcast on players from 50 years ago and I came across his incredible story. Thank you very much and enjoy your evening…