The Day of Fake News

Fake news has been much in the news. There have even been reports that some of the propaganda that people who voted for Trump swallowed ravenously were stories planted by Russia. Paul Horner, who makes a living doing fake news, also claims he got Trump elected.

“Honestly, people are definitely dumber,” he told The Washington Post. “Nobody fact-checks anything anymore—I mean, that’s how Trump got elected.” This is how so many people became convinced President Obama was not born in the U.S. and was a Muslim.

Although the term “fake news” may be new, the concept is not. It has long been used by countries in warfare. Winston Churchill said, “In wartime, truth is so precious that she should always be attended by a bodyguard of lies.” During the same World War II era, the Japanese people thought they were winning every battle until bombs began falling on their houses. They were not told when four of their aircraft carriers—the heart of their navy—were destroyed in a single battle at Midway, just six months after those same carriers devastated Pearl Harbor.

In normal times, however, major news organizations have generally agreed on basic facts, even if their editorial opinions varied. Alas, this is no longer true. Today, political parties, and media which favor them, cannot agree on facts. That was noted years ago when Sen. Daniel Patrick Moynihan warned that “everyone is entitled to his own opinion, but not to his own facts.”

That was just about the time that political operatives began doing exactly that. Convinced that the press was unfair, they began seeking new outlets for their own “facts” disguised as news. An early and glaring example was the 1968 presidential campaign, when Roger Ailes, then a young producer of “The Mike Douglas Show” in Philadelphia, convinced candidate Richard Nixon to let him manage the media aspect of his campaign.

He shielded Nixon from the mainstream press. Instead, Nixon appeared in a series of town hall meetings, which were packed with supporters asking questions arranged in advance, designed to make Nixon look as if he were candidly talking on tough issues, when really it was all clever propaganda. Joe McGinniss’ book The Selling of the President 1968 exposed all of this. That best-seller made Ailes and himself famous. It also set Ailes on a path to create his own media form that would report the news his way, but it took almost 30 years before cable expanded the media landscape and enabled him to launch Fox News.

It was fitting that both Ailes and McGinniss were in Philadelphia at the time, for in the1960s the Philadelphia Inquirer, then owned by Walter Annenberg, was a corrupt operation. Annenberg blacklisted people he did not like. One was Milton Shapp, who ran for Pennsylvania governor. An Inquirer headline at the time read that Shapp had denied being in a mental institution. But nobody had said he was.

Annenberg also hated Matt McCloskey, who had owned the rival Philadelphia Daily News. McCloskey became ambassador to Ireland, but Annenberg never let his photo appear in the Inquirer. Then, at a political function, McCloskey managed to get himself in a photo taken for the Inquirer. He was between President Kennedy and Philadelphia Mayor Richardson Dilworth. He gleefully told people they could not keep him out of the paper. But the next day a gray blob appeared when the photo ran. McCloskey had been airbrushed out of the shot.

And when the Philadelphia Warriors moved to San Francisco, Annenberg was upset. A few years later, he suspected the Warriors’ old owner was behind the city’s new NBA team. He wasn’t, but for a period of time the 76ers got two paragraphs when they won, only one when they lost. Hard to believe? It happened.

Annenberg’s reputation for vindictiveness was so widely known that one of his pet employees took advantage of it. Harry Karafin was Annenberg’s hatchet man. When Karafin called, powerful people shuddered. For several years Karafin ran a shakedown scheme, threatening investigative stories, while a public relations accomplice suggested the potential target could use some PR advice. Karafin did not run fake stories; he faked running them. Among those who paid thousands in his extortion scheme was Philadelphia’s largest bank. Karafin was eventually exposed by Philadelphia magazine. He died in jail.

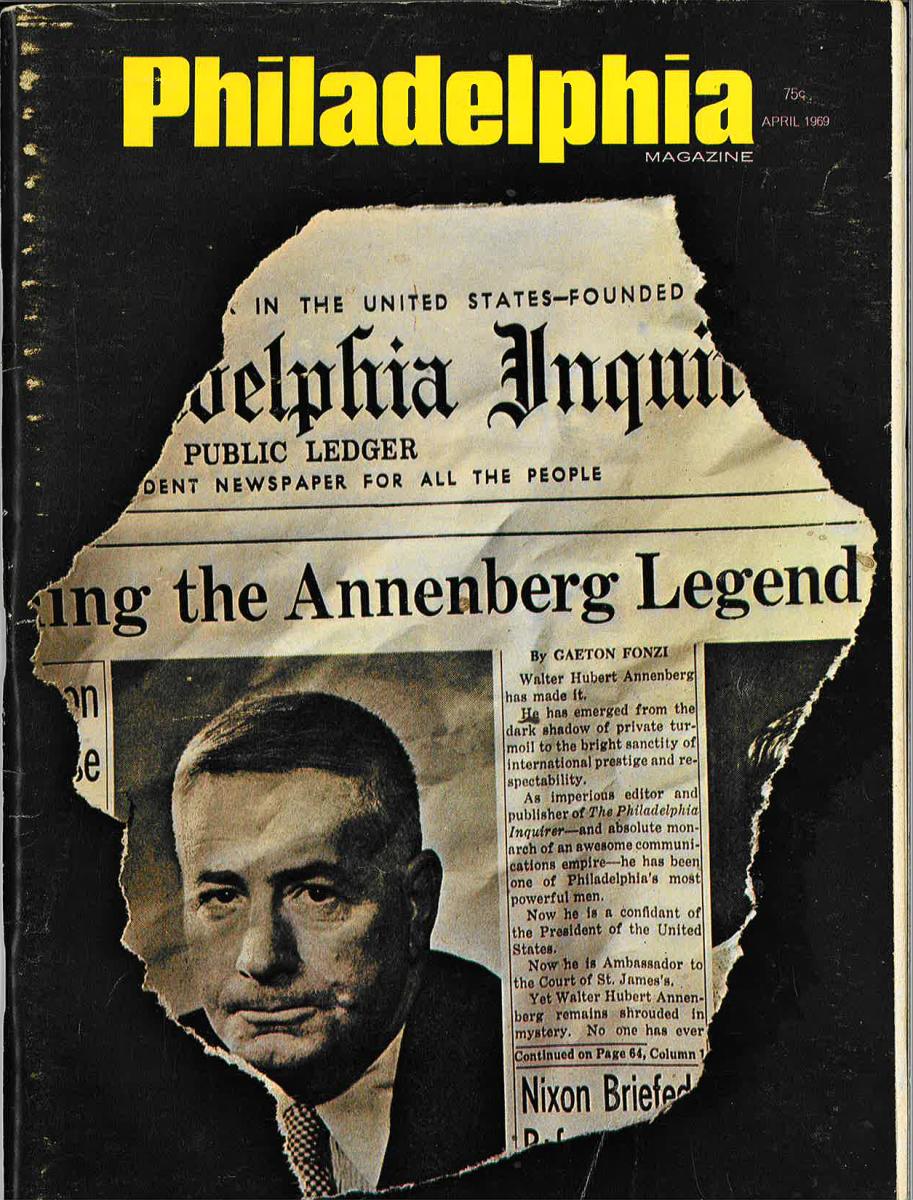

The co-writer of that story, our late Gold Coast magazine partner Gaeton Fonzi, later wrote magazine articles (above) and followed up with a book on Annenberg, detailing his decades of abuse of power. Shortly thereafter, Annenberg sold the paper to Knight-Ridder, at the time owner of the Miami Herald. The new ownership turned it into one of the best papers in the country, winning 19 Pulitzer Prizes over ensuing decades.

Today the purveyors of fake news do not go to jail. But they should.

Image via Philadelphia magazine