Making Don Shula Nervous

The deal closed in the late summer of 1970, but we didn't move down until January of '71. It took months for us to have much impact on a magazine called Pictorial Life. Like the rest of the magazine, the name was sort of meaningless, unless you counted the classy advertisers who filled its pages. We adopted the name Gold Coast in stages. It was the only name that described our market from Hollywood to Palm Beach.

We also made editorial improvements at a pace. Compared to the award-winning Philadelphia Magazine we had left, the book was amateurish. There were a few serious columns (one written by future Broward County Commissioner Anne Kolb), but most of it was advertising fluff. The design was not much better. The previous owner boasted that she never paid for a photo. In an effort to speed things up, we began doing sports features. An obvious story was the Miami Dolphins, only in their second year under a new head coach, Don Shula. They were the only professional team in South Florida. We knew Shula had coached at Baltimore, but we identified that team more with their hard-nosed quarterback, Johnny Unitas.

Shula's first year had been impressive. He had turned a losing team into a winner. His second season was going surprisingly well. By November the Dolphins were on a winning streak, and the team was drawing big crowds and getting a lot of ink, including the playful "Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid" photo of running backs, and off-field buddies Larry Csonka and Jim Kiick. We decided it would be good reading to follow the team for the rest of the season, especially since the Super Bowl was scheduled for Miami.

We were ill-prepared for the task, but that was nothing unusual. Until that fall we had barely heard of Csonka and Kiick. The only names we recognized were Nick Buoniconti, Bob Kuechenberg and Bob Griese - only because they had played for or against Notre Dame. Also Paul Warfield, because he had become celebrated on championship Cleveland Browns teams. In reading over the old story, it is clear we also had some contact with probably the biggest no-name on the now renowned "No Name Defense." That was Doug Swift, a rare pro from Amherst College in Massachusetts who literally tried out for pro football on a lark. That connection was through a young writer on our staff who had gotten to know him. He later would write an entertaining story on this most unusual football player.

With nice cooperation from the team, we began hanging out at practices, going to the home games and made arrangements to follow the team on the road. Our trips had an ulterior motive. We had other business in the north.

After a few weeks of lurking around practices and the locker room after games, Coach Shula began to notice. We had not made any effort to talk to him, and it was making him nervous.

"Don't you want to talk to me?" he asked one afternoon in the practice locker room. We replied that we intended to, but at that moment did not know enough to ask sensible questions. He was such a controlling figure that he wanted to know what strange reporters covering his team were up to. This was not a negative as far as reporters were concerned. A Philadelphia-based reporter had told us that when it came to all aspects of a coach's work, including dealing with the press, Shula was the best. And he thought the latter was an important part of being a successful coach. As his career lengthened, Shula made it clear that being a community ambassador was part of his role.

All writers covering the Dolphins saw that side of him. Sun-Sentinel columnist Dave Hyde wrote in a recent Shula appreciation: "Everyone had his home number - and he didn't just think you'd call late at night if needed. He demanded it, he wanted his voice to shape a story. He grew upset if he wasn't called."

At games, we sat in the press box near Miami Herald guys, including Bill Braucher and Herald sports editor Edwin Pope. We had learned enough over the years to pick the brains of those who knew the most about the subject.

We also spoke to out-of-town writers in Baltimore and New England. They were uniformly impressed with the newly powerful Dolphins.

Some of the glow came off the team when they lost both those road games, but they still managed to get to the Super Bowl. In retrospect, it was an amazing job that in just two years Don Shula had taken basically the same players he had inherited from a far below average team and turned them into a Super Bowl contender.

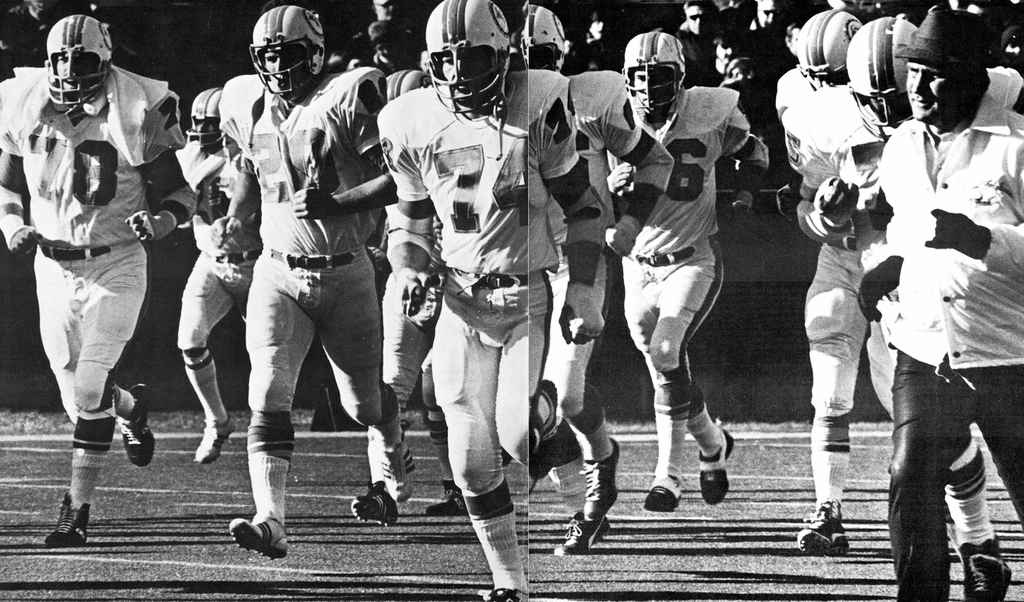

And we did get to interview Shula. Maybe twenty minutes of uninspired questions and canned answers. In further retrospect, the trip to New England had an unexpected benefit. That game was in early December and we had to break off our story in time to get it in our January issue. Later than that, it would lose impact. We had hired a photographer through friends at Boston Magazine. We just told him to work the sidelines and shoot anything that moved. When we got his pictures we were immediately taken with one, so much so that we ran it as a double page in the story.

It was an unusual shot, unlike anything we had ever seen, and as the years passed it became ever more dramatic. It is one of our favorite pictures in Gold Coast's 50-year history. It shows a young Don Shula on a cold afternoon, his game face on, leading a determined-looking team onto the field. No matter that they lost that day. It still has great prophetic impact. It depicts a coach and his team charging into legend.

And they next season they did.

Bernard McCormick had a second interview with Don Shula years later. It was far more memorable and we will discuss it in our next blog.