17 and Counting

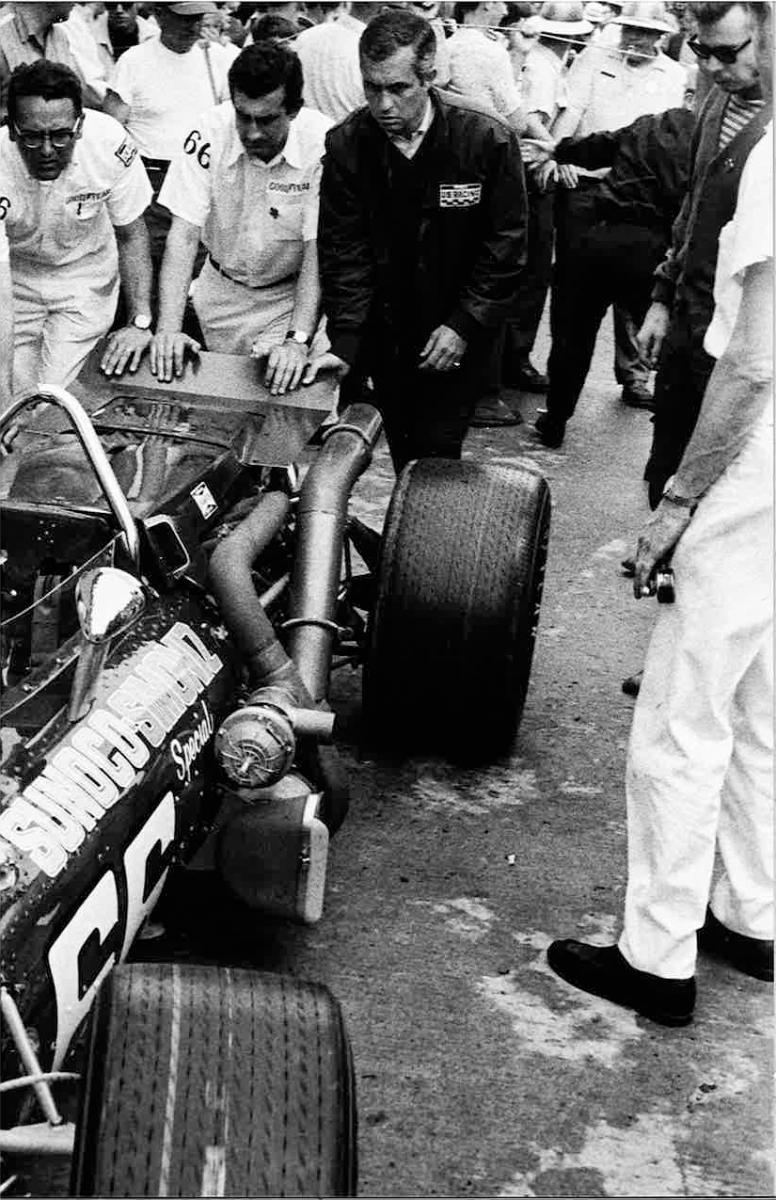

Always a hands-on manager, Penske helped push his racer off the track during time trials.

It was 7:30 a.m. Monday following the 1969 Memorial Day Indianapolis 500. The owner was at his desk signing letters. He had 130 of them, all thank yous to people who had been helpful to him for the last month.

“It doesn’t take much time and people appreciate it,” he explained. The owner had his own Chevrolet dealership in West Philadelphia, which he had purchased after working three years as its general manager. The dealership was his job. As a sideline he also owned a racing car team, which had just participated for the first time in the greatest spectacle in racing.

For a rookie team, it had gotten an extraordinary amount of publicity. It had a big-time sponsor, Sun Oil Company, headquartered in Philadelphia not far from the auto dealership. The race car, an innovative four-wheel drive Lola, had been the talk of the race. His driver, although new to the oval track, was already becoming a legend as one of the most successful sports car racers of the day. He was a novelty in the sport—an engineer with a degree from Brown University who contributed to the design and technical aspects of his own racers. The team had lived up to its press, turning in some of the fastest times in qualifying.

However, the team did not win (Mario Andretti did), and the owner was disappointed, but hardly discouraged. His car had been running third late in the race before engine problems forced it out, and into a seventh-place finish. The thing that went wrong was almost a freak—a magneto had failed, shutting down the engine. However, the months of preparation, including most of the month of May spent in rookie qualification and time trials, had been a valuable learning experience. The owner seemed confident his team could win at Indy. He thought it would take three years.

He was wrong, but not by much. Roger Penske took four years to win his first Indy. Mark Donohue drank the victory milk in 1972. Three years later he was dead—cerebral hemorrhage a few days after crashing in practice for the Austrian Grand Prix. Penske, who stopped driving himself after a spectacular crash in a sports car race, lives on. Last weekend he won the Indianapolis 500 for the 17th time. LeBron James’ extraordinary basketball feat on the same weekend pales beside it. Talk about records that will never be broken. The two second-most winning Indianapolis owners—one of whom is Michael Andretti—have five. And, at age 80, Roger Penske is not finished.

What makes Penske so successful was apparent that morning almost 50 years ago when he was signing thank you letters at 7:30 in the morning. They had obviously been prepared in advance. The race had been on a Friday, and the next two days following the big event are always hectic. There are award dinners and teams breaking down their garages to go home. It can be very tiring, but here was Penske on the next working day at his office at the crack of dawn. Any fool could see him coming.

What took this fool to Indy for Penske’s 500 debut was largely a business decision. Philadelphia magazine was trying to develop automobile advertising. It began doing stories to support that effort. It did a piece on luxury cars and the guy who sold Rolls-Royces. We rented a limo for a day and wrote about the thrill of driving around town thumbing our noses at the poor slobs driving 10-year-old rust buckets. One of the writers even rode with a motorcycle gang for a few weeks. And then we decided to do something on auto racing. Stock cars were not the magazine’s audience, but a young fellow who had begun getting some notice as a sports car racer when still a student at Lehigh University was more our speed.

I had never seen an auto race of any kind, but my first car had been a 1958 Porsche (used but in immaculate condition), and my second a small BMW sedan, one of the first in the country. Only motorcycle buffs recognized the blue and white propeller emblem, a recognition of the company’s start as an aircraft engine builder. So I was aware of the racing history of those brands. When we read that Penske was jumping from road racing to the big time of Indy, and his sponsor was Sunoco, whose office was around the corner from the magazine, it seemed like a natural.

I contacted Penske more than a month before the race. He could not have been more cooperative, taking me to the suburban Philadelphia facility where his car was being prepared, letting me ride on a private plane with him back and forth from Indy in the weeks before the race, and arranging for me to be on the grid as the drivers got that famous “Gentlemen, start your engines!” command. He must have sensed how little I knew about racing, but was too tactful to say it.

His touch with the press is one of the qualities that has served the man now known as “the captain” so well over his career. From the start he was meticulous about detail, a demanding boss who drove his mechanics crazy by insisting they break down engines that were running fine. Penske became famous for the phrase “the unfair advantage,” meaning a better race car and driver. But he was always gracious in a game that back in that era had its share of rough characters. Those 130 thank you letters tell the story.

That year at Indy there was always a mob scene around his garage. Penske, whose nature is order, would get upset about all the people hovering over his mechanics, and order everybody out of the garage. Then, spotting a writer standing outside in the masses, he would motion you to come back in. He did this with others until within minutes the garage was crowded again.

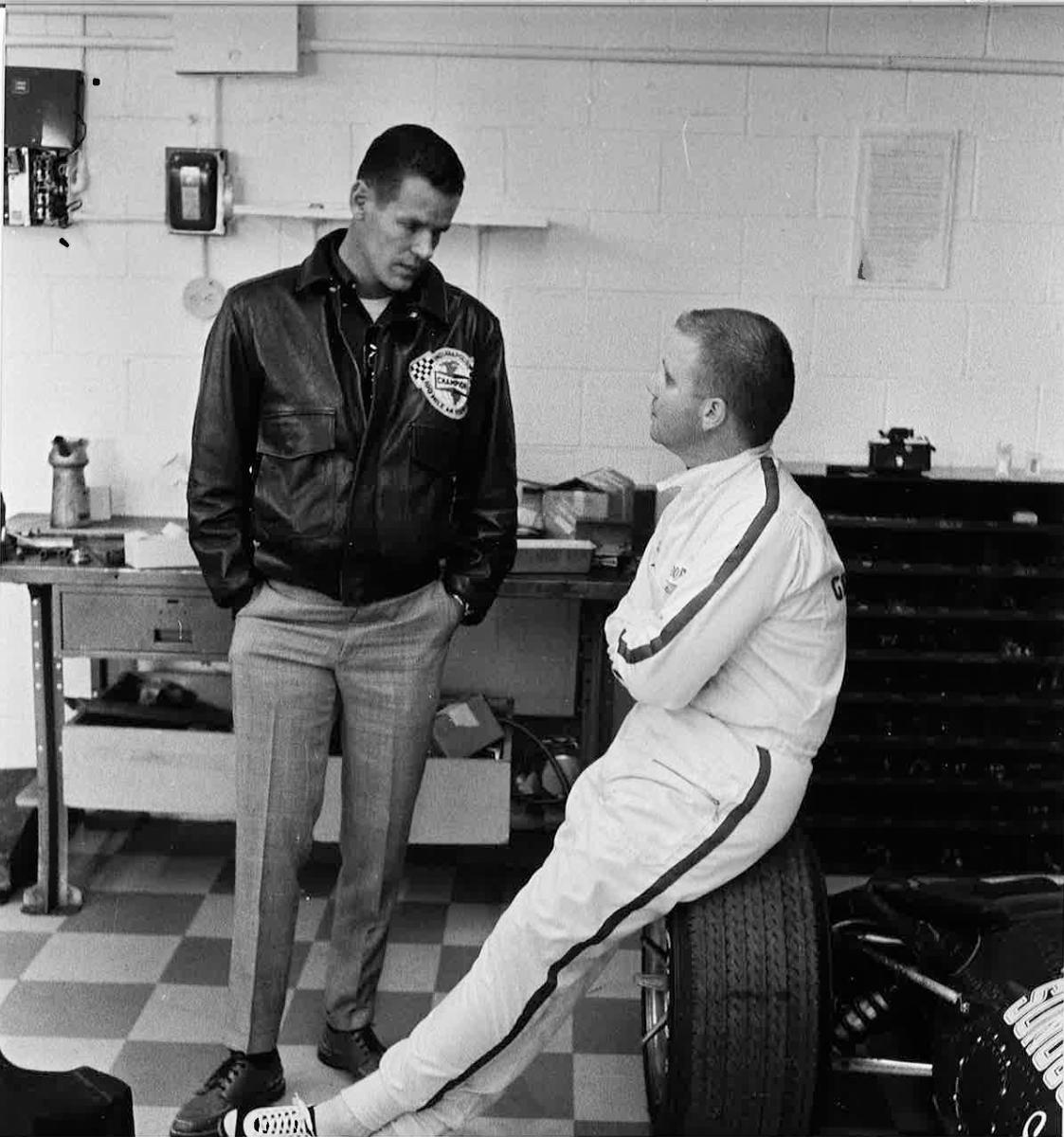

His close relationship with Mark Donohue was palpable. Donohue was reserved and quietly polite, with a soft face that masked his fiercely competitive nature. The combination of personalities inspired the title of Philadelphia magazine’s piece: “Captain Nice and Mr. Clean at Indy.” I am not aware that he ever said much about it, but Donohue’s death at the height of his fame must have been the hardest blow that Penske had to take over the years in a dangerous sport.

Penske’s talents and discipline have taken him far beyond racing. He has been a remarkably successful businessman. You see Penske rental trucks every day, and he owns auto dealerships and has number of corporate boards. He mentioned that goal on one of the flights from Indy to Philadelphia in 1969. People were predicting he would get into politics, and I asked him about it, and what he wanted to do with the rest of his life. He was 32 at the time. He seemed to ponder the question, as if not sure of his answer, then replied, “I’d like to be known as a good businessman.”

He never mentioned 17 wins at Indy.

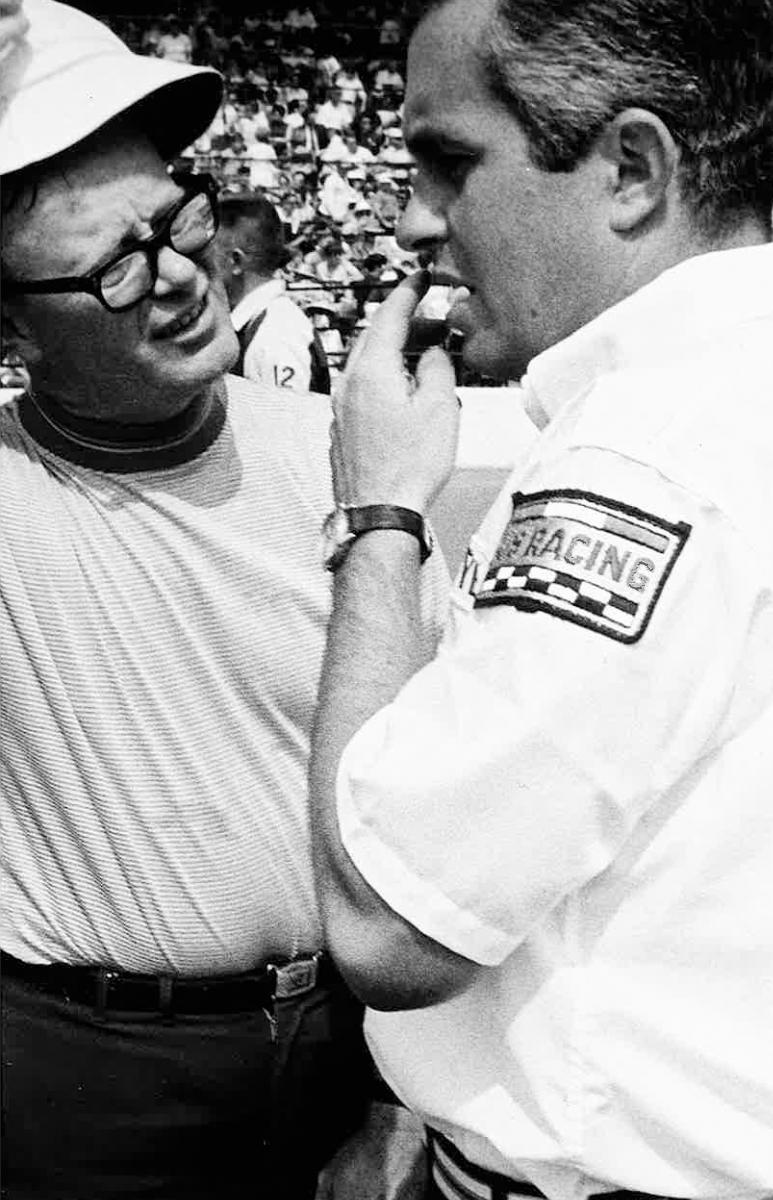

Roger Penske’s rapport with the media was always excellent. In 1969 he was interviewed at his first Indy 500 by Philadelphia sports writer Sandy Grady.

Even as a rookie owner, Penske’s garage attracted racing stars. Bobby Unser, (left) of a legendary racing family, visits with Mark Donohue.