JFK- Clues to The Truth

Those of us survivors who have followed the history of the Kennedy assassination and its controversial aftermath are finally getting some answers to questions that popped up soon after that tragic day 55 years ago. Or, more accurately, we are getting clues to answers, if not direct answers themselves.

One of the troubling aspects of the assassination has been the lack of action by major news outlets in questioning the official government version that Lee Harvey Oswald acted alone. Sure, there have been a plethora of books and articles written challenging that conclusion, but very little of that activity began with major news outlets. Television and newspapers merely reported what private investigators had uncovered.

That strange silence began even before the Warren Commission issued its 1964 report. No less an institution than The New York Times praised the work of the Warren Commission, but it took some time before skeptical researchers discovered that the Times’ assessment came before anyone on its staff has actually seen the full report—the 26 volumes of evidence that were full of inconsistencies and testimony from numerous witnesses that the commission chose to ignore.

Over the years major news organizations have seemed reluctant to accept conspiracy theories, even as they reported on them in detail. And in some cases, major newspapers have simply ignored dramatic information that appeared right under their noses.

We saw this up close and personal when our former employer, Philadelphia Magazine, printed one of the first articles casting doubt on the Warren Commission’s work. In 1966 Gaeton Fonzi interviewed Arlen Specter, the man who came up with the notorious “single bullet theory”—an idea necessary to support the single gunman conclusion. It was a long, detailed article, which created quite a stir locally when Specter could not explain his own theory. It actually led 10 years later to Fonzi being hired by Pennsylvania Sen. Richard Schweiker to take part in the reopened investigation of the crime.

However, at the time, the Philadelphia papers ignored Fonzi’s work. Specter continued to get favorable publicity as the man who had proved how a lone gunman killed a president. His growing reputation led to election as a U.S. Senator, an office he held for 30 years. There have been other examples over the years of important media ignoring stories in their own markets. One of the most glaring again involved Gaeton Fonzi. By then he had joined us in Florida as editor of Miami Magazine, which was sold in 1975. That’s when Sen. Schweiker contacted him to work for the government.

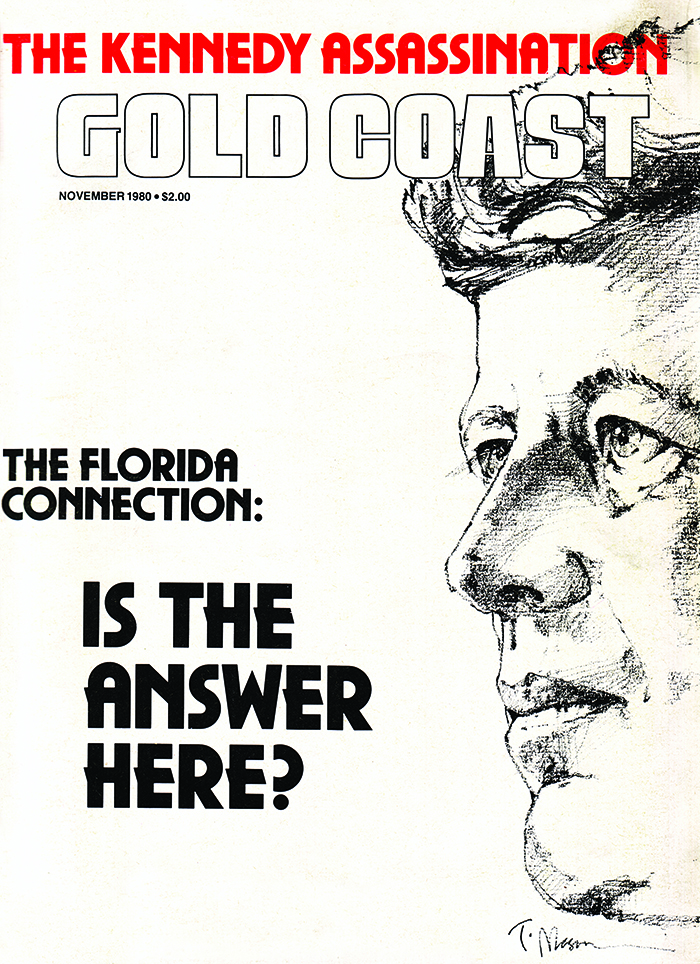

In late 1979, with five years of work behind him, Fonzi published a two-part article in Gold Coast magazine and The Washingtonian. The latter was an important magazine in the nation’s capital, and Fonzi had unusual credibility. He was now an insider who had dealt directly with the CIA and saw the agency’s efforts to sabotage any legitimate inquiry. In his articles, which later became “The Last Investigation,” regarded as one of the best books on the subject, Fonzi vented over the failure of two congressional committees to answer the question of who killed JFK. He had discovered a strong CIA connection to Oswald in the form of a high-ranking CIA officer who was heavily involved in anti-Castro activities in South Florida, but the House Select Committee on Assassinations, pressed for time and money, never fully followed up on that dramatic revelation.

Gold Coast could not have played the story any bigger (see cover above), but the local South Florida papers never mentioned it. The same thing happened in Washington, where Washingtonian was long established and highly influential. It sensationalized the story with a provocative cover, which resulted in the CIA officer suing for libel. He lost, but the magazine spent a lot of money defending itself. Despite all this, the former Washingtonian editor, Jack Limpert, said The Washington Post never carried a line about the story. Keep in mind the timing. This was almost 10 years after the Post showed great courage in breaking the Watergate story. More than strange.

Which brings us to the point. In recent years it has become known that major newspapers had CIA connections at the time of the Kennedy assassination. It only made sense. Reporters were stationed around the world. It was their job to have contacts that the intelligence community would find helpful, especially in places such as South Florida with all its Cuban anti-Castro activity. It did not mean that reporters were paid agents of the CIA, but it did mean they might sense a patriotic obligation to help gather intelligence when asked. And, quid pro quo, the CIA could be a valuable source of information to them. They had to be on good terms to keep up with the competition.

The fact that some reporters even had CIA code names was revealed years ago. It has long been known that the Miami News, which expired in the late 1980s, had one such reporter. Hal Hendrix impressed colleagues with his inside information on intelligence activities in Cuba and Latin America. He even won the Pulitzer Prize. But he blew his cover in 1963 when he revealed a CIA-sponsored coup in the Dominican Republic—the day before it actually happened.

And just last week the Miami Herald broke the news that among recently declassified Kennedy Assassination documents were several references to two of its own former reporters having CIA connections. Kevin Hall, a much-honored editor who works for McClatchy Newspapers out of Washington, D.C., revealed in a full page piece that the two Herald reporters, Don Bohning and Al Burt, now both dead, had CIA clearances and were assigned code names. Both covered Latin America at one time, and Burt later wrote prominent columns in the paper. Does this mean their contact with the agency was anything but normal for men in their position? Hall does not know. But it does support researchers who as early as 2005 claimed the CIA had friends at the Miami papers who could be counted on to keep some stories quiet, while promulgating others.

The more cynical among us—those close to important stories such as Fonzi’s, which were ignored by local papers—suspect that the CIA influence went beyond the newsroom grunts, and may have involved high levels of management. The initial reaction of The New York Times to the Warren Commission Report is one example. Perhaps a better one was the legendary The Washington Post editor Ben Bradlee, a friend of President Kennedy. You would expect him to be a leader of the charge when the doubts about the Warren Commission were first publicized. But he was also the brother-in-law of a high-ranking CIA officer and was close to the agency’s top leadership. He would have been reluctant to associate his social friends with such a terrible crime. In an interview with David Talbot for his 2007 book Brothers, Bradlee admitted that when the first questions about the assassination arose in the mid-1960s, he was new to his job and concerned about his career. But that insecurity does not explain why his newspaper was silent when Fonzi’s magazine article roiled Washington 15 years later, after his paper’s brilliant Watergate work, and he had become a hero played by look-alike Jason Robards in the film “All The President’s Men.”

Bradlee is gone now, so we will never know his true thoughts. All we are left with are clues. And the clues keep coming. Perhaps someday they will lead to answers.

Image: Gold Coast magazine's November 1980 cover.