Iwo Jima - Lifting the Fog of War After 78 Years

Sunday, February 19, will mark 78 years since the wake of hundreds of landing crafts foamed the sea off a place most Americans had never heard of. It was a small island called Iwo Jima, and it was taken by the U.S. Marines in the bloodiest battle of the Pacific in World War Two. Before it was over, 7,000 Marines had been killed and 20,000 wounded, along with 22,000 Japanese defenders, almost all dead.

This painting by the late Fort Lauderdale artist Bob Jenny set off a remarkable chain of events.

Those American casualties were largely Marines, but other services took some losses as well. One of them was a Navy pilot, flying perhaps the only Navy plane to go down the day of the invasion. He was Lt. JG Thomas McCormick, my cousin. There was a certain mystery about his death, one that was not explained until six decades had passed. We will get to that.

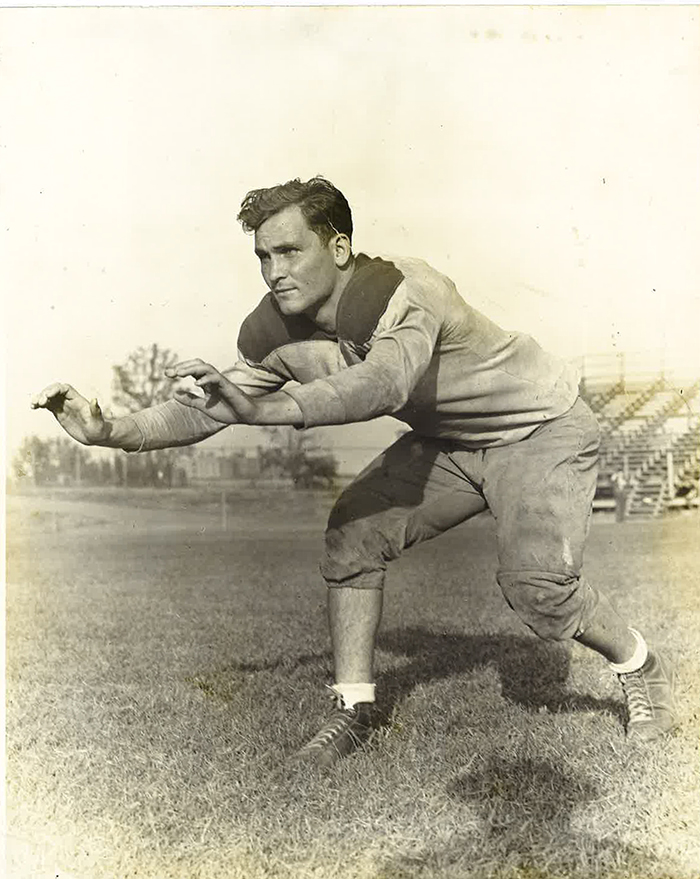

Tommy was a special man. His father, a year younger than my dad, had married young, my father not until 37. Thus the 15 years between us. I was eight years old the Christmas of 1944 when he came home on leave, less than two months before he died. I remember him as if it were yesterday, sitting around our breakfast table in his Navy blue uniform, a big, athletic and strikingly good-looking guy who was held in affection by all his relatives. He had grown up between Atlantic City and Philadelphia – his father was an alcoholic and separated from his mother. He had been a high school football star and played for what is now La Salle University, on the last team the school had before it dropped the sport in 1942 because so many of its students had left for the war.

Tommy McCormick in his practice uniform at La Salle University in 1942.

Tommy flew a Chance Vought Kingfisher, the Navy’s float plane used for aerial observation and water rescues. It was catapulted from large ships, in his case the battleship USS Tennessee. He was lost during the Iwo Jima invasion, and for years that’s about all the family knew. The standard telegram to his mother in Atlantic City said he was missing in action, and the family waited a year hoping that, like a number of Navy pilots, he might show up on some remote island. In fact, he was never missing. Hundreds of men on ships saw his plane go down, and the Tennessee listed him as killed in its monthly report. It was also strange that Tommy’s mother never got a visit from a Navy representative, the usual protocol in such circumstances.

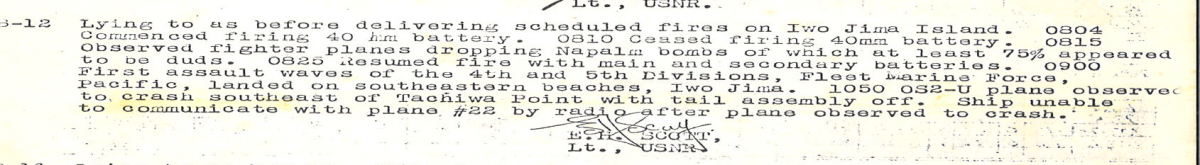

The mystery deepened decades later when my brother Frank, a Navy officer in Admiral Rickover’s nuclear program, decided to check the log of the Tennessee on that fateful morning. It revealed that Tommy’s plane broke apart without an explosion or signs of battle damage. Its tail assembly missing, it plunged quickly into the sea. Tommy and his observer never had a chance to bail out.

That struck us as strange, for the Kingfisher was a sturdy machine, capable of taking the stress of catapult launchings and rough water landings. The explanation came through a remarkable coincidence. The late Fort Lauderdale artist Bob Jenny, who loved painting aircraft, did a painting of a Kingfisher over the Tennessee the day of the invasion. It hangs in my office. When I learned about the USS Tennessee Museum in Huntsville, Tennessee, I sent a copy, thinking it might interest them. The response was startling. The museum founder and curator, Paul Dawson, knew exactly who Tommy was. He even had photos we never knew existed, including one of Tommy flying his plane. It turned out his father had been the ship’s photographer and knew the handful of pilots aboard. He even flew with them to take aerial shots. He identified Tommy in photos he saved for decades.

USS Tennessee Museum curator Paul Dawson found this photo, never seen by the family, of Tommy McCormick piloting his plane.

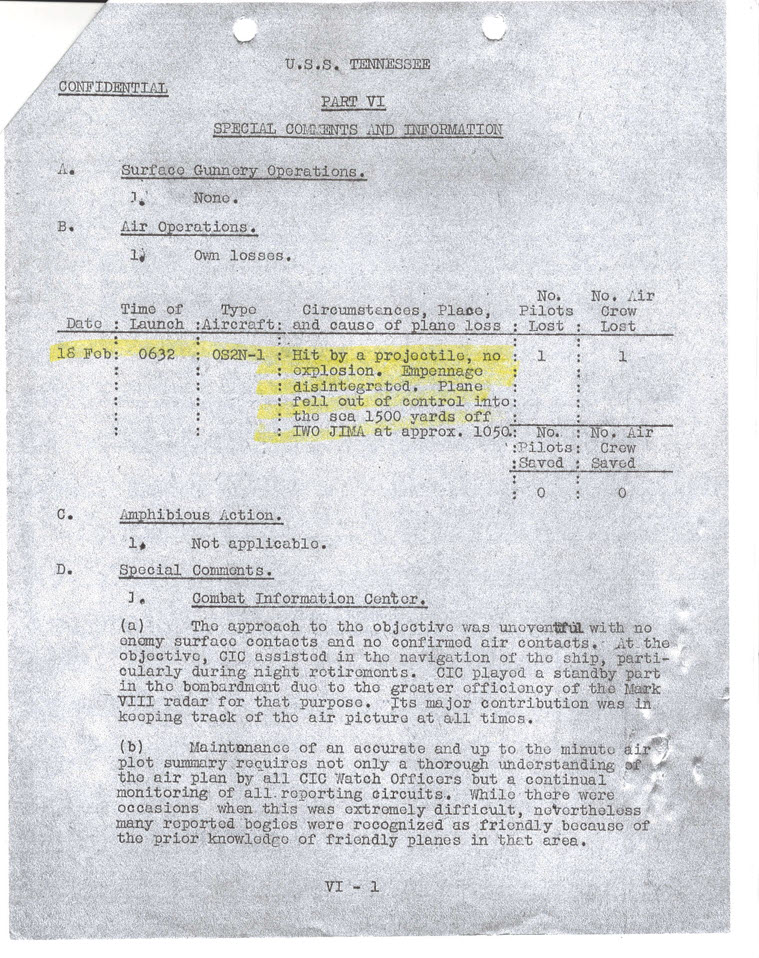

Dawson took over from there. He searched the ship’s records and found that Tommy had crashed a plane in a rough water landing on his first tour to the Philippines in late 1944. Then came the bombshell. He discovered a confidential Iwo Jima “after battle” report that said that a projective had been seen to hit Tommy’s plane and knock the rear completely off. And in its concluding paragraphs, it said that it was possible that an errant shell fired from a long-range Navy gun may have been that projectile. It recommended that steps be taken to assure spotter stayed above the trajectory of the guns they were directing.

The first hint of the strange circumstances of Tommy's death was found by Frank McCormick in the log of the Battleship Tennessee.

That explained why there was no explosion when Tommy was hit. A large caliber shell would easily go through a small plane without exploding. And if the Navy suspected that happened, you can be pretty sure Tommy was killed by friendly fire. That also helped explain why the family never knew what happened. The report was confidential, and even after the war the Navy would not want to tell his grieving mother that her boy was killed by friendly fire.

This "after battle" report, supplied by Paul Dawson, was confidential and probably not seen since 1945. It suggests death by friendly fire.

But somebody obviously made a big mistake on that day. It was already standard procedure for pilots, even at relatively low altitudes, to keep well above the gunfire they were observing. And, by Iwo Jima, Tommy was experienced in obeying that rule, as were the gunners on the big ships.

So, as the fog of war lifts, a new mist appears. We can’t find an exact timeline, but Tommy was in the air an hour before the first marines hit the beach at 9 a.m. The Japanese deliberately let the landing site become crowded with men and equipment, who had a hard time moving across the surprisingly soft volcanic ash. Then, they put their clever plan into action. The initial opposition the Marines encountered had been at ground level, until they were surprised by devastating fire from hidden positions in caves on Mount Suribachi which overlooked the beach. Many of their casualties occurred in those first hours. Several days later the Marines captured it, memorialized in the famous flag-raising photo.

It would seem obvious that the supporting Navy ships would quickly shift from nearly direct fire on ground targets to the new higher ones on Suribachi. Tommy’s plane was hit about 10:50. It went down off Suribachi, suggesting he was in position to observe that target. Could it have been that the big Navy guns were elevated to hit the higher targets before Tommy’s Kingfisher could gain the necessary altitude to stay above their trajectories? What we may have here is a failure of communication. We probably will never know.

After 78 years, the fog of war can be persistent.