The recent Super Bowl controversy over the halftime show and other events, even including the coin toss, brought to mind something written years back about a most unusual Dolphins player. Doug Swift was the biggest no name on the famous 1972 No Name Defense of the only undefeated team in NFL history. Swift was different from go - he played college at Amherst, better known for its academic distinction as a Little Ivy school than for its sports program. Football was simply a pause before his real career in medicine. He only tried out with the Dolphins when it was suggested that Don Shula's young team might be interested.

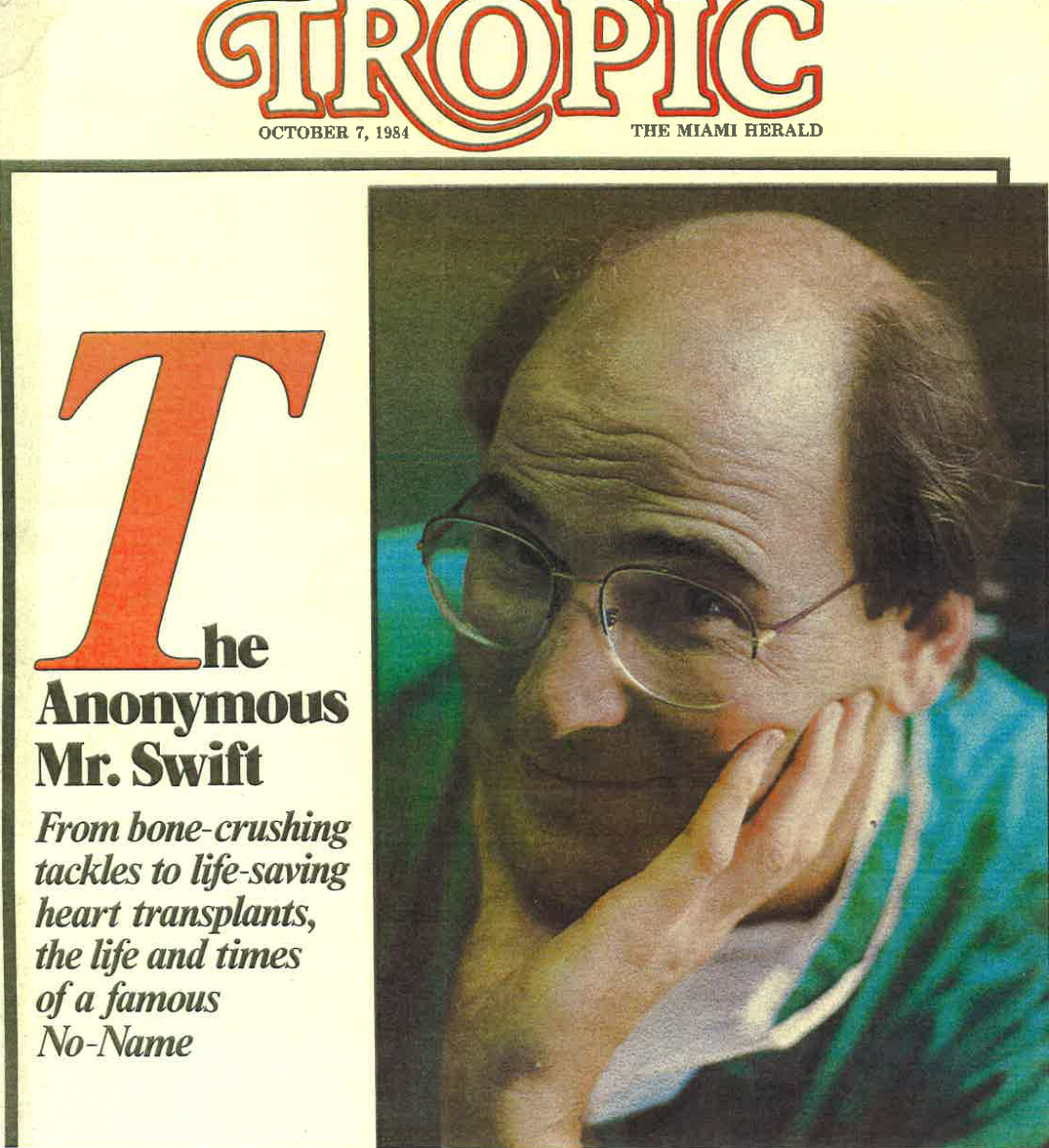

Both his parents were doctors. He was an art major at Amherst but achieved the considerable task of taking pre-med courses while playing with the Dolphins. It did not take him long to establish a reputation as an anesthesiologist. We looked him up when in 1984 an item appeared in a Philadelphia paper about his being part of the team that performed the city's first heart transplant. He could not have been more gracious. He gave us the rare opportunity to watch his Temple University Hospital team in open heart surgery. That turned into a cover story in the Miami Herald's old Sunday Tropic Magazine.

Swift's shaggy hair was in recession during his playing days. Eight years later it changed his appearance. That impish little smile was familiar to his teammates.

Back to football. Midway in his six-year career with the Dolphins, he gave Gold Coast magazine a remarkably candid interview which bears retelling in the current context.

"Things went well in Miami right from the beginning," he said. "I felt that they liked me. I was easy to coach, and it wasn't a very good rookie group that year. Also, I could read. I think they liked me because I could read."

That type of line was common with Swift. He often spoke irreverently of the game he played so earnestly. He resented politicians, notably President Richard Nixon, sticking their noses into the game. He was irritated by all the pre-game ceremonies, including lengthy pre-game prayers.

"The bullshit that takes place on the field before the game is ridiculous. You are ready to go and then you have to go through that bullshit. It's like a bad joke. There's no need for those prayers, those invocations."

If that makes him sound bitter, Doug Swift was hardly that. He was a friendly guy, a good locker room presence, liked by his teammates. He laughed easily and his normal expression was a half-smile. His comments about the game must have been shared by other players 50 years ago. And they applied to the game in general, not the premier event of the season. One can only imagine their reaction to all the hoopla nonsense we put up with today.

"Ask most little boys what they want to be when they grow up, and they'll say an astronaut or something like that. All I ever wanted to be was Louis Armstrong."

Troy Anderson spent 12 years in Europe.

So spoke Troy Anderson on a recent visit to las Olas Boulevard, where his boyhood dream actually became reality. It was the early years of the century when he worked as a bartender at O'Hara's, a popular bar which featured musical entertainment. Anderson, blessed with the right skin color, had been playing the trumpet since age 10. He could sing and developed an excellent imitation of Louis Armstrong's memorably growly raspy voice. He had done his imitation a few times on active duty in Germany, but it was more than two decades before he again picked up his horn to entertain.

"When I went to O'Hara's, nobody knew I could play," he says. At cocktail hour, when not too busy, he pulled out his trumpet and went into the Armstrong bit. He worked near the front door and passers-by stopped and came into the bar to listen.

O-Hara's, which closed in 2008 to allow for the expansion of the Riverside Hotel, was owned by Kitty Ryan. We recently wrote about Wells Squier whose designs established the charming Las Olas look. In a different way, Kitty Ryan made a similarly important contribution. Before her, Las Olas had little nightlife. O'Hara's changed that dramatically. Her Sunday concerts featured jazz and blues and packed the place. At night O’Hara's became a press hangout, and Kitty Ryan pioneered outside dining which is now found up and down Las Olas.

When Ryan realized she had a uniquely talented bartender, she gave Anderson shots on Sundays. His reputation for his Louis Armstrong imitation quickly spread and he began getting gigs in other venues. Sensing the opportunity of a lifetime, he formed a band. "The Wonderful World band was born at O'Hara's," recalls Anderson. "Kitty helped me get gigs at other places. She helped me in every way she could, for which I'm very grateful."

After Anderson polished his act with appearances around the country, he decided to try Europe. He was so successful that he spent the next 12 years abroad, beginning in Poland (which he loved) and playing in a number of countries, eventually expanding to a half dozen cruise lines. "At one time I spent seven straight months on ships," he says.

Today at age 64, he considers himself semi-retired. "I'm not working in bars anymore, but I still get gigs. I've gotten a nice warm welcome back, so I'm feeling pretty good. I'm cherry picking my spots."

He's also spending time in the Bahamas where he was born and spent time back and forth from Florida growing up.

It’s safe to say life is a lot more comfortable than it was then.

"Oh yeah, I go to the Bahamas to chill. It's beautiful, very pleasing to the soul. It's a moment of clarity."

Clarity, as in a little boy's vision of his future.

This recent week was a historic one for Las Olas Boulevard. Two events promise to change the character of Fort Lauderdale's charming shopping district. One, the opening of Huizenga Park on the western perimeter of the boulevard, adds a beautiful recreational dimension to a neighborhood with so many tall buildings for blocks around it. The other, more to the east in the original commercial district which began with the Riverside Hotel in 1936, is a controversial development which many think will detract from the boulevard's appeal. We have a personal interest in both situations. The dedication of Huizenga Park featured artwork by the area's young artists, one of whom is our grandson, Colin Breslin. He was part of the team which painted the large mural on the west side of the park and also was one of the artists who painted umbrellas which were part of the opening festivities. A recent graduate of FSU, Colin is building his reputation in the niche muralist art form, evidenced by his first solo effort - at Scouting America in Davie.

Colin Breslin was among artists featured at Huizenga Park opening.

The redesign of Las Olas's oldest section was approved by the city despite opposition from many residents who frequent the boulevard. It will replace the shaded median with broader sidewalks, narrowing the boulevard from four lanes to two. It will broaden the sidewalks to relieve the current busy sidewalks and permit more room for outdoor dining and other activities. New trees will be planted in the broader sidewalk. The project is viewed as a benefit to the stores on both sides, but we have a hard time envisioning anything that will not deprive the boulevard of its present ambiance.

On a personal note, the new design will require the removal of a plaque in the median toward the east end of the boulevard which remembers a man who was once strongly identified with Las Olas. That was Wells Squier, who for decades influenced the formation of the Las Olas charm. Squier was an industrial designer whose work goes back to the 1950s and continued until his death in 1993. Among his ideas are the fake facades of a number of the original stores which give the impression of second stories. Prominent developer-banker Jack Abdo, who lives the nearby Colee Hammock, asked us to write the inscription for the plaque years ago. Squier was so identified with Las Olas that he literally died there. His body was found in his car parked just off the boulevard. He suffered an apparent heart attack following a lunch nearby. Today, there is barely any mention of him on the internet. All glory is fleeting.

Plaque to Wells Squier was installed shortly after his death in 1993.

One argument for removing the historic median is that the distinctive trees are on their last legs and will have to be replaced anyway. We are among the cynics on that score. It is the same excuse developers use when they cut down old oaks in surrounding neighborhoods to permit much larger buildings, often apartments which replace the homey cottages which stood for years. It is true that most of those old trees have some decay in the heart of their broad limbs, but those trees, many a hundred years old, are a long way from dying. It is an unfortunate trend. Developers are attracted to these shaded old Florida neighborhoods, then destroy the very thing that attracted them in the first place. Go figure. And you will figure money.

Next to the current president of the United States, the worst thing to happen in this young century is the professionalism of college sports. We know that some unethical programs have been figuring out ways to secretly pay athletes for years, but now it is wide open. In the past few weeks of the college football playoffs, it has become common for stories on the big matchups to mention how much money the star players are making. Thus, we know that Indiana's Heisman winning quarterback Fernando Mendoza, who came out of Miami’s Columbus High, is earning around $2 million, after turning down almost twice that from the University of Miami. Those big bucks came after he showed his ability at the University of California, where he reportedly got a measly $100,000. The quarterback he will face on the championship game against UM tonight, Carson Beck, also jumped ship from Georgia for an increase in compensation to an estimated $4 million. A stunning 65 percent of Indiana's starting lineup are transfers.

Fernando Mendoza holds the Heisman Trophy after his historic season.

It has reached the point where the average scale for various positions, both offense and defense, at big time teams is being published. Some players earn more money in college than they would likely get for turning pro. College athletics, once the essence of amateurism, have become a minor league for the pros. The justification for this sad situation is that college football has become a huge money-maker for schools; why not share that money with the players who make it happen?

The principal reason why not is that it is a perversion of college sports. For the few dozen top football schools that benefit from it, hundreds of smaller schools with modest football programs, or none at all, are being denied the opportunity to succeed against the big boys. And the whole concept of school spirit, the "win one for the Gipper" mentality, is being lost. How long are fans going to have an almost religious devotion to their alma mater, or hometown school, when players to whom they have become attached, routinely leave through the portal, and players they never heard of show up in their place, and may in turn chase money after one season? Consider Robert Morris whose recent NCAA basketball tournament team lost its entire starting team to the transfer portal. Or James Madison, whose coach took 14 of his players when he was hired to build the current Indiana powerhouse. Closer to home, our alma mater La Salle has a basketball tradition. Several national championships and three players of the year. Its great star Tom Gola, set a rebounding record that has stood for 70 years. But today, La Salle can't afford to pay for top talent, and each year its best players enter the transfer portal.

With famous coaching figures such as Nick Saban calling for reform, there is a growing sense that the present state of college sports cannot continue. There are various ideas to change it, so here is ours. Go back to the old days when a sports scholarship included tuition, room and board, and a stipend to help with other expenses. If players were wise, they would value their college degree (if they graduate) because if they can't make it as pros, which the great majority won't, their education could be the difference between a blue-color job and a white-collar opportunity that would make a comfortable life. Make it uniform for all schools, big or small. And if an incoming athlete wants to make more money, let him turn pro. Establish a minor league such as baseball, or to a lesser extent pro basketball. There are actually semi-pro football leagues, The players often have been cut by NFL teams and have full time jobs, and are looking for a second chance. And in a few cases, that happened. But there is no formal minor league as in baseball.

Our guess is the most promising high school athletes won't go for it. The enormous publicity that goes with being a college star can lead to a lucrative pro career. No such attention would be paid to a kid making money by playing for a team in Ocala, Florida or Norristown, PA. Making a minor league system that fans actually supported would be a big job, but the problem it might solve - the destruction of college sports - is even bigger. We need to return to the day when "win one the Gipper" means something.

There was a time; it does not seem so long ago, that when you turned on TV news, as almost everybody did, you could hear Walter Cronkite on CBS, Huntley Brinkley on NBC and a pretty well-known figure such as Harry Reasoner and Barbara Walters on ABC. And when they reported news, they all said pretty much the same thing. Nobody doubted their word, and you never heard a spokesman for a different point of view cutting in to create doubt.

Walter Cronkite was called "the most trusted man in America." The perversion of today's media would likely appall him.

There were no cable outlets tailoring their reporting to please their audience and slanting the facts on many stories to attract more viewers. Newspapers, with notable exceptions, also told the same stories, although their editorial pages reflected the points of view of their publishers. Nobody could envision the avalanche of opinion blogs are primary sources for so many people and are often blatantly biased.

We recall that era nostalgically in view of what is happening to media today. It began innocently. Ted Turner launched CNN in 1980, the first full-time cable channel. The station did news, but also featured interview shows that were often strong on opinion. Then came Fox, the fulfillment of a dream Roger Ailes talked about for years. He felt the mainstream media leaned Democratic, and he wanted an outlet for Republicans to counter it. Ailes started with a claim of "fair and balanced" but over the years Fox has turned into a propaganda arm of the Republican party. It got so bad that in defending a lawsuit its lawyers took the position that Fox was an "entertainment' outlet, rather than a conventional news channel. In other words, people should not take us seriously when we damage a reputation. We are just having fun.

Before Fox, TV news was held to a high standard. The mainstream channels were careful to be accurate. But since Fox, all manner of podcasts and blogs have appeared, as a group commanding a sizeable part of the total audience. And prominent political figures have become increasingly reckless in making unfounded statements which can harm reputations and even endanger people. The Trump administration has adopted the outlandish position of accusing news makers they don't like of criminal actions.

The New York Times recently highlighted the problem, using the case of the Brown University murders, in which an immigrant was initially identified as a suspect, but quickly cleared. But by then various outlets and public figures had jumped on the bandwagon, endangering the innocent man's life. The Times complained that those spreading falsehoods are rarely held to account. For many people truth has become what they want it to be. The result is too many people with low or misinformation. That can be worse than no information at all. How else can you explain Donald Trump?

It may be far-fetched, but we would encourage a New Year's resolution to address this media crisis, perhaps even making the spreading of deliberate misinformation some kind of crime.

"A day which will live in infamy." Sunday was Dec. 7 and it was once described by a president of the United States in those memorable words. Any student of American history will instantly recognize the context, and most people who remember anything about World War II will as well. But we suspect the average college student will not. We say that because we found nothing in several newspapers or on television in reference the Dec. 7, 1941 and the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, an event which took what had been a conflict confined to Europe and made it world war - a war of such horror and death total that it ranks as one of the major events in recorded history, and certainly of American history.

Three stricken U.S. battleships. Left to right: U.S.S. West Virginia, severely damaged; U.S.S. Tennessee, damaged; and U.S.S. Arizona, sunk, December 7, 1941

It shows that President Franklin Roosevelt's eloquent speech to Congress declaring war has not lived in infamy, although for years it was prominently noted in most media. But as the veterans of that war have passed on, the stories of their experiences have gradually slowed down. It is not a rare phenomenon. November 22, the date of John f. Kennedy's assassination, has similarly tended not to be remembered with the impact it had for years. 9/11 still is mentioned often, but give it a few years. It is the nature of things.

Pearl Harbor day was once almost a national holiday, and it seems that the date should be memorialized in some form - similar to how Sept. 15, 1940 still is commemorated as "Battle of Britain Day.” Few people alive today were directly impacted by Pearl Harbor day, but millions of families live with a history of its profound impact on the immediate ancestors. Our family was, and not just because our favorite cousin, Tommy McCormick, paid the supreme sacrifice. He was a college student when the war began but dropped out to train as a Navy pilot. He was a reconnaissance pilot who died at Iwo Jima in what years later appears to be a death by friendly fire from the ships he was spotting for.

Our own family suffered a consequence of that day as well. Our dad had been working for what was then Sears, Roebuck for 20 years. He was a plumbing and heating specialist for Sears pre-fab housing unit headquartered in New Jersey. It had once been a busy place; its houses were perfect for the depression years, enabling cash-strapped people to buy homes they could assemble themselves, but as the economy recovered, Sears decided to close that business. Dad managed to get a transfer to Elmira, New York, running the plumbing and heating department of its store there. He apparently did well. He was recognized in 1941 for his years of service. But then came Pearl Harbor. Mother wanted to return to be near her many relatives in Philadelphia, and Dad was able to get transferred back to Sears’ big facility in Philadelphia where had started out. He had barely settled in when he lost his job. In what now seems a serious miscalculation, Sears thought its business would suffer with so many customers joining the service. It decided to cut back on middle management personnel. Dad recalled that the executive charged with choosing whom to let go was a man he had started out with years before.

"I did not like him and never took pains to conceal it," Dad said. "He remembered." Dad was 50 years old with three young sons. He wound up in the insurance business, which he never much liked. He must have felt betrayed by life. Our family went from relative prosperity to living hand to mouth until we grew up and got out on our own. In a strange way, we were a casualty of Pearl Harbor.

We were wondering how to end this ramble, when Monday's Sun Sentinel arrived with a front page teaser leading to a lengthy article of exactly the kind we had not seen this year = a piece on the sparse turnout in Hawaii at the annual event remembering Pearl Harbor. No ancient veterans of that day were present, and their descendants determined to recall the Day of Infamy are dwindling in number.

The meaning of Dec. 7 has survived for another year.

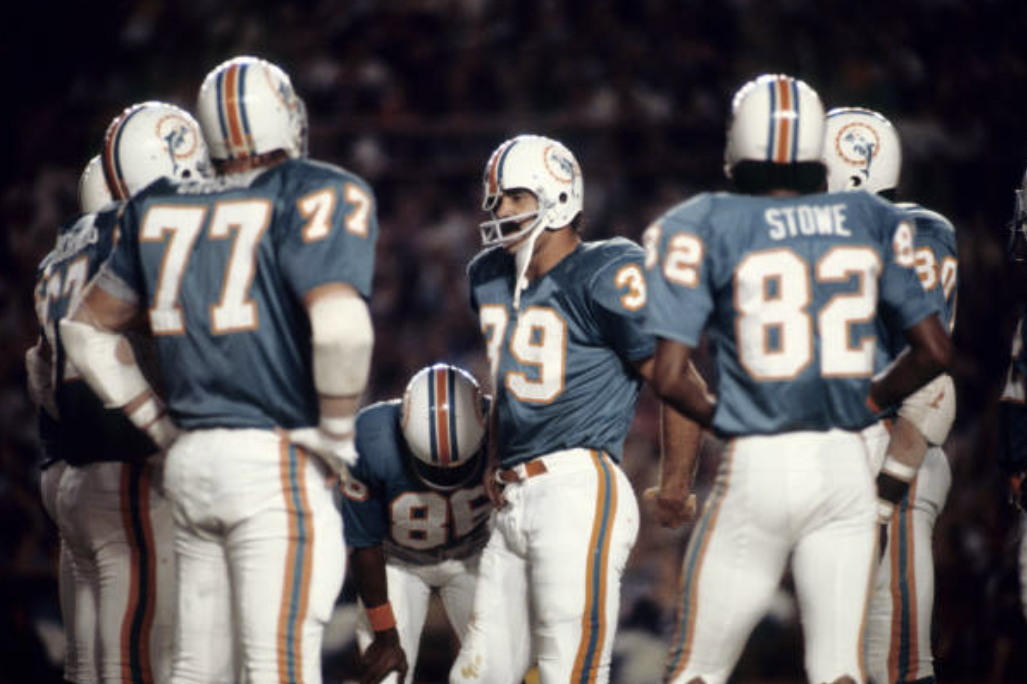

The year was 1971 and our newly acquired magazine, which would evolve into Gold Coast, needed serious work. The book was filled with people dancing for disease and ads for those trying to sell them real estate and interior design. It obviously needed broadening. One expansion route was sports. The area had a new football team, the Miami Dolphins, and with a successful coach Don Shula, it was beginning to create interest. The team was called the Dolphins, not a creature associated with aggressive behavior desirable in football, and had unusual colors, aqua marine and orange, which seemed a bit effeminate for a big-league team. We followed the team that season and were impressed by its rapid improvement and emerging stars such as Larry Csonka, Bob Griese, Paul Warfield, Nick Buoniconti and Larry Little. Just a year later this group became the only undefeated team in NFL history. The aqua marine color now stood for the essence of masculine success.

The 1972 Dolphins made aqua a championship color.

Miami Dolphins new uniforms revealed. Dolphins Deloser look is bluer than the old classics.

When a team becomes that successful, its uniforms become part of its legacy. Fans expect them to always have that winning look. Fans buy replica jerseys, and its logo appears everywhere from pennants to coffee cups. Thus, it attracts our attention in a bad way when a winning team messes with their winning look. This happened in an egregious way recently when University of Miami, in an apparent salute to our military, came out in the ugliest suits ever seen on a college team. Playing against a mediocre SMU team, the Hurricanes did not look like themselves, and sure did not play like themselves. They suffered a giant upset, that devout people might associate with God's displeasure.

Miami is not alone in messing with their uniforms. Notre Dame created a fuss on the internet early this year when they came out wearing white pants instead of their traditional soft gold. But that was nothing compared to a few years ago when they disgraced the Golden Dome by dressing for a game like praying mantises. The white pants got immediate criticism on the internet. Fans complained that it looked like they were watching Navy or Georgia Tech. In a more recent game, Notre Dame returned to its traditional gold pants against Syracuse. It is doubtful they would have scored 70 points in those stupid white pants.

Speaking of Navy, it has been experimenting with all blue uniforms that look like a bad abstract painting. Interestingly, they dressed as in the days of Roger Staubach and played Notre Dame tough for a half in a recent game.

Back to the Dolphins. Back in the glory days of the 1970s we never recall the team wearing anything but all white on the road. They never wore aqua pants. Dark pants make players bottom heavy and deprive them of their best form. But in recent years the Dolphins have worn dark pants often and paid the price. Compounding that sin is the fact that their base uniform color, although still officially aqua marine, was changed a few years ago to a light blue. We first thought it was a color problem with the TV. until we noticed that the numbers on white jerseys were still the original aqua. Why the Dolphins gave up their iconic aqua is a mystery, but we wonder if the decline of the team in recent seasons is punishment for this egregious act. There are names for many shades of blue, some of them with French accents. So let's call this one Deloser blue.

As one who saw firsthand the Dolphins make aqua marine a record setting color, we strongly suggest the Dolphins honor that legacy by returning to that color. If they look like champions, maybe they will play that way again.

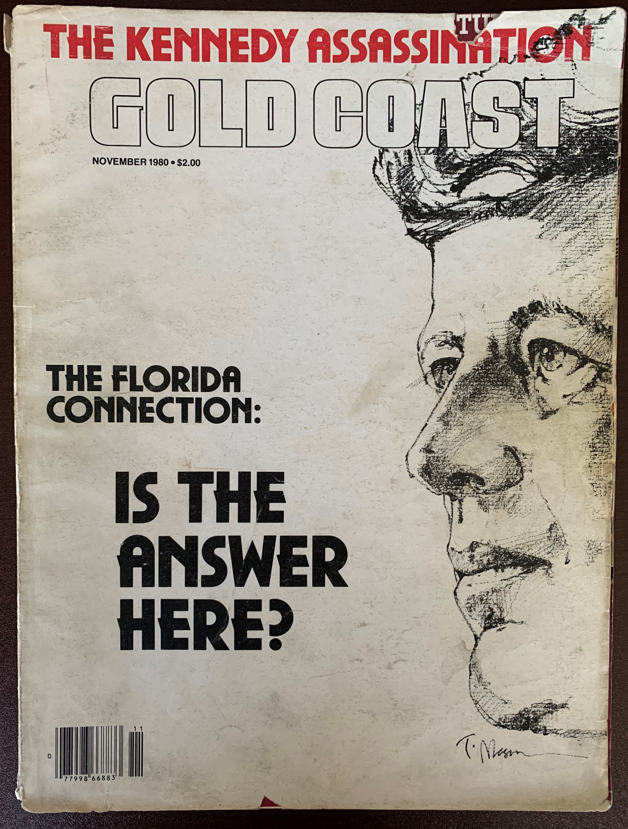

Jefferson Morley is a leader among the second generation of Kennedy Assassination experts. We say second generation because Morley was only five years old when JFK was killed. He has, however, relied on the best of the first generation of critics - those who were involved in the early challenges to the Warren Commission's conclusion that Lee Harvey Oswald alone committed the crime. Our former Gold Coast magazine partner Gaeton Fonzi, in Philadelphia Magazine, challenged the Warren commission soon after its report in the mid 1960s. He later was a key investigator when the government reopened the case in the 1970s. Fonzi's book The Last Investigation was written in response to his disappointment in his House Select Subcommittee on Investigation's failure to solve the crime - largely because the CIA sabotaged its work. That book first appeared as long articles in Gold Coast. Fonzi’s work expanded with several printings, and the New York Times called it one of the best books on the assassination in its obituary of Fonzi.

Jefferson Morley

Fonzi’s work first appeared in 1980 in Gold Coast Magazine.

Morley mentioned Fonzi in a recent article in which he revealed the CIA's role in obstructing that investigation. Morley referenced recently released JFK documents which meant little to most mainstream reporters, but, due to his detailed knowledge of past revelations, enabled Morley to make connections to the CIA's role in the crime. As a result, Morley has flatly accused the CIA of engineering the crime and its elaborate cover up.

Morley found additional evidence to support the previously known efforts of the CIA to hinder the JFK investigation, beginning with its control of the Warren Commission in the 1960s. A few months ago he reported that the CiA managed to infiltrate the 1970s investigation in a blatant way. Fonzi and other investigators were complaining that the CIA was not cooperating with their work. The agency responded by assigning a man named George Joannides to facilitate the flow of information. He provided little help and years later we found out why. It turned out that he was the man assigned to track Lee Harvey Oswald when Oswald was being manipulated by the agency. A man likely involved in the plot to kill Kennedy was hardly one to help solve it.

Gaeton Fonzi reported that audacious incident in one of his last pieces on the assassination shortly before his own death in 2012. Not much has been written about Fonzi's work since his passing. With the anniversary of the murder coming up this month, it is good to see that a a respected JFK researcher like Morley has not forgotten our former colleague.

Our dinner party was driving from east Las Olas, at the top of the islands, to meet us at the Riverside Hotel. Ordinarily, that nine-block trip takes about five minutes, sometimes a little longer on busy nights. When the party was 15-minutes late, we called to find the problem. Extremely heavy traffic, we were told. Another 15 minutes passed, another call. Traffic not moving at all on Las Olas. It was 45 minutes before our party arrived, and we were suspicious when they said at a traffic light they were three cycles when nobody moved. The problem, as we now know it as gridlock, was cars coming from a few side streets, getting stuck in the middle of the intersection, blocking the street so nobody could move. We thought they were exaggerating to cover their lateness. Until we drove back the same Las Olas route. It was still bumper to bumper, stopped cold, all the way for 10 blocks. Welcome to the future.

We had just read a Sun Sentinel editorial lamenting the influence of lobbyists on the government bodies who vote on growth issues. These are people who make a living representing developers, influencing and making decisions that often favor the developers who hire them, often in the face of strong opposition from neighbors. They usually say how the latest monster building is a great boon to its neighborhood, and ignore the increasing burden on the city's infrastructure. Fort Lauderdale has its best neighborhoods on the east side of town, and every increase in downtown traffic hurts the quality of life in these neighborhoods.

Those who still read the Sun-Sentinel had to be amused by a recent article in which city commissioners and others who are allowing increasing big buildings justified their behavior. One commissioner was quoted as saying "people want to come here," as if they had a moral obligation to welcome newcomers. Quite a contrast from the attitude on newcomers on a national scale. Imagine Donald Trump welcoming immigrants from all over the world because they want to come here.

When we read about the downtown growth of recent years, our thoughts drift back to Bill Farkas. Farkas became Downtown Development Director in the mid-1970s. He took the job when downtown's highest building was Landmark Bank, nine stories tall. Much of the downtown was run down. Las Olas was quiet. A previous development director had gotten the city in a mess by illegally razing older blocks. Worse, Farkas suffered the humiliation of not even being told that his biggest employer, Burdines was moving its big department store to the new Galleria Mall, where it is now Macy's.

Bill Farkas was popular in a role that often involved controversial decisions.

Farkas' first win was converting the former Burdines location to a government center, holding a base of workers on a site that featured the community leadership. Progress came slowly. At one point, tennis courts were built just off Las Olas, giving the impression that something was happening. Then came a few new buildings, along with some upgrading of the stores on Las Olas. Farkas, dealing with conflicting interests, developed a reputation for tact and fairness. His upbeat and winning personality made him one of the most popular public figures of his time. Over the next 15 years, he brought downtown attractions, including the NSU Center for the Arts, a new library, the Discovery Center, and facilities for Broward College and Florida Atlantic University. By the time he left as development director, development was noticeable. Farkas' crowning achievement was yet to come. His reputation for competence earned him the job of building the ambitious Broward Center for the Arts on an artificial mound on Las Olas west of Andrews Ave. It spurred the renewal of that depressed neighborhood. Wayne Huizenga's Blockbuster, located nearby, and a whole block of restaurants appeared just west of the FEC railroad tracks. Wally Brewer's Olde Towne Chop House and the Tarpon Bend restaurant across the street became hot spots.

By 2000, his success in redevelopment was producing a reaction from residents concerned that it was too many high rises, too fast. There is no record of his commenting on the subject, but his work over the next decade is telling. He had lived in Miami Beach, and he took over leadership of preserving historic buildings in that neighborhood. By the time of his death in 2019, one has to think that the accelerating redevelopment in Fort Lauderdale may have him wondering if he had been responsible for dramatically altering the city's ambiance. On the other hand, there are worse legacies than being too successful.

We used to have a standard joke whenever the name Villanova came up, usually in a sports context. "Villanova's not a very good school," we would say, "two of my brothers got in there."

With the recent news that the new Pope attended Villanova, we have to modify that old line, for this new distinction is right up there with Villanova's NCAA basketball championships. The truth is that our family's connection to Villanova is strong, not unusual for a former Philadelphian. Villanova is just west of that city, an early stop on the famed Main Line. And the family connection is overwhelmingly positive. Two of our brothers attended Villanova on Navy ROTC scholarships, and both went on to earn doctorates, John (better known as Mike) in engineering from Columbia and Frank, from the University of California in Berkley. Both had interesting careers in their respective choices. Frank was honored by Villanova as a distinguished alum.

Frank McCormick, Ph.D., was honored as a distinguished alumnus by Villanova in 1984. He is flanked by Rev. John Driscoll, president of Villanova, our mother Sara Sweeney McCormick, and our cousin Margaret Sweeney Schneider and her husband Jack. At the time Frank was vice president and director of economic research for Bank of America. Margaret Schneider spent 40 years with the Villanova alumni office.

There is more. Our cousin Margaret worked in the alumni office for 40 years, and just last year grandson Tommy McCormick graduated with a major in economics. In recent years, helped by its basketball prowess, Villanova has enhanced its national reputation. Increasingly Catholic high school students in Florida consider acceptance to Villanova a real achievement, up there with Notre Dame and a handful of long-respected schools.

The addition of a Pope to its roster of graduates is a further distinction - a different kind of V for Villanova.