One of the great discoveries in this year of fascinating politics is that while many presidential candidates are ambitious and competent, they must also be likable—the kind of person we’d like to share a beer with.

This we take from articles about the candidates, notably Sen. Elizabeth Warren, who many people find difficult to love. She comes on as school marmish, lecturing us on her plan for just about everything. Other candidates, in their quest to be noticed in the crowd, may appear to some as unseemly aggressive, forgetting in the heat of debate that bad form is what they are all running against.

The inference is that this is something new—that past nominees running for high office didn’t need to be likable, just qualified to do the job. History begs to differ. As far back as we have film to record their personae, the most likable men seem to prevail in presidential elections.

Teddy Roosevelt was immensely popular; his powerful personality overwhelmed opponents until he tried the impossible—running on a third party. A few years later his cousin Franklin Roosevelt could be engagingly charming, despite the burdens of his times, at least in contrast to the three dour men he ran against. Harry Truman had the likable qualities of a common man, upsetting the more serious Thomas Dewey in 1948.

“I like Ike” speaks for itself. The smiling war hero, Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower, was a sharp contrast to the intellectual Adlai Stevenson. And then came John F. Kennedy, whose wit and charm overcame the much better known Richard Nixon, whose stiff presence and shifty eyes could never shake the “Tricky Dick” nickname.

Gerald Ford was famously good-natured, which along with a sympathy vote after Nixon’s downfall, helped him win over Jimmy Carter. Carter edged him in the next election, but the peanut farmer fell victim to Ronald Reagan’s classic good nature.

And so it has been. More recent elections have been closer in the personality department, but the more likable candidate has usually prevailed. They must charm their way to victory like the rest of the winners.

We were thinking of a way to celebrate Gold Coast magazine’s 55th anniversary next year. We can’t make quite the big deal we did for the 50th, with a fancy dinner and a special issue devoted to our history. This time we were considering publishing a hall of fame—people who appeared in our magazine for outstanding contributions to the community over the last 55 years. Most would be deceased, although there would be exceptions for people such as Don Shula.

We got the idea when we mentioned the name Theresa Castro to several people in their 20s. They had no idea who she was, and barely knew the term Castro Convertible, the business she and her husband Bernard built into an American icon. They were one of the first to use TV for advertising, with spots featuring their young daughter Bernadette showing how easily a child could open a sofa into a bed.

Theresa, an extrovert, and Bernard, just the opposite, supported everything in Broward County. Their lavish parties in Broward and at a sprawling ranch in Ocala are fondly recalled today by a dwindling few.

Among other names from the past that came to mind was Bill Maus. No, not the Bill you are thinking of. It is his father, who in 1940 came down from Petoskey, Michigan, and with partner Frank Hoffman opened a high-end men’s clothing store, Maus & Hoffman. Their success marked the beginning of Las Olas Boulevard as a popular shopping street. At one time, there were a dozen stores from Petoskey that followed Maus & Hoffman to Las Olas or other South Florida locations. Maus & Hoffman is the only one that survives.

The original Bill Maus was a champion of Las Olas. At the time, the boulevard had no good restaurants. He backed Louis Flematti in opening Le Café De Paris, which lasted for 50 years. When the elder Maus died in 1980, his oldest son, Bill Jr., took over as family patriarch of the growing Maus family and held that role until this week, when he died at age 88 at a second home in Lake Geneva, Wisconsin.

Bill Jr., was one of four siblings to work for Maus & Hoffman. His late mother was active in the business. His brother John runs the Palm Beach store. His late brother Tom worked with him on Las Olas, and a sister Jane Hearne ran the Naples store. There are still a number of family members in the business, including Tom Jr. who heads the Fort Lauderdale store, recently relocated to the Riverside Hotel. Bill Jr. never retired. He worked until the last few months of his life.

Bill Jr. carried on his father’s community spirit. In addition to his work on Las Olas, he was a generous supporter of his alma mater, Notre Dame, and St. Anthony Catholic School, which he and his seven children and numerous grandchildren attended. He was on the boards of Holy Cross Hospital and Ave Maria University. His many activities made the pages of Gold Coast numerous times.

He and his late wife Jane (Bidwill) found time to travel extensively, including frequent football weekends at Notre Dame. He will be buried in a cemetery there.

A number of descendants still work for Maus & Hoffman, but others in the large clan have branched prominently into finance and other fields.

The family asked expressions of sympathy to be made in donations in his name to St. Anthony Catholic School Development Foundation or Catholic Central High School in Burlington, Wisconsin.

A funeral service will be held Saturday at noon at St. Anthony Church. You can expect a large crowd to honor a memorable man and a life well lived.

This is being written during D-Day anniversary week. Media attention has been focused on France and the WWII Normandy invasion, popularly known as D-Day.

A major difference between press coverage in WWII and today’s limited engagements is that casualties in recent combat have been far lighter than in wars past. Accordingly, the death of a single soldier often gets considerable coverage. Recently CBS’s “60 Minutes” repeated a segment originally broadcast several years ago about the deaths of five soldiers in a friendly fire incident in Afghanistan. It featured several men on the unlucky team who knew immediately that our own aircraft had killed their comrades.

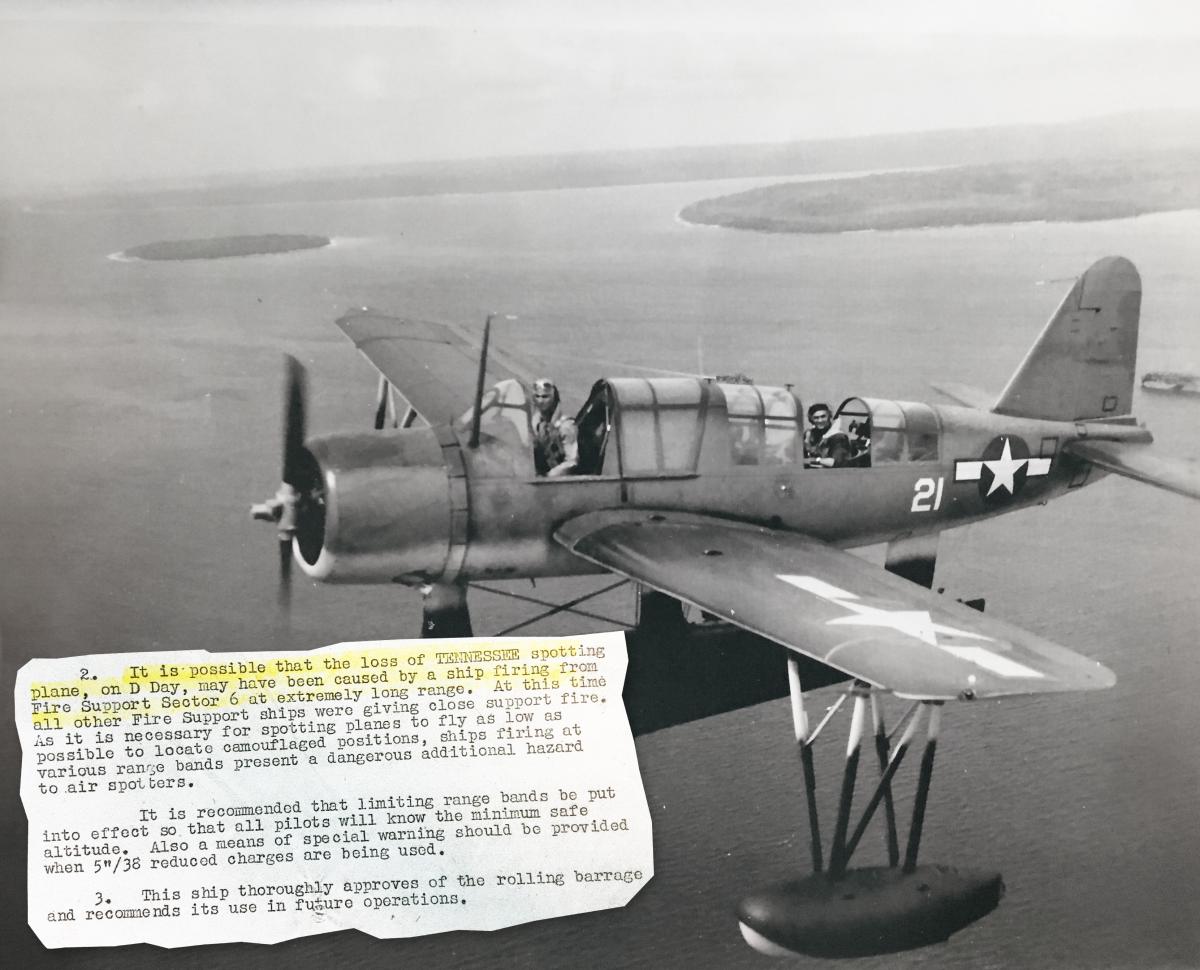

Assigning blame was tricky. CBS even brought in a general to comment. There was no doubt that it was a tragic case of friendly fire. Nobody could cover that up. It struck me as a startling contrast to a WWII likely friendly fire death in the skies above Iwo Jima. My cousin, Lt. J.G. Thomas McCormick died when something struck his small spotter plane flying off the Battleship Tennessee on the morning the Marines landed to begin one of the bloodiest fights of the war.

For years, that’s all the family knew. A great looking guy was missing, then pronounced dead. There was much more to the story, but that took 60 years to learn. We had contacted Paul Dawson who runs the USS Tennessee Museum in Huntsville, Tennessee. We were amazed to learn he knew of my cousin. His father had been the ship’s photographer and had photos of the handful of pilots who flew its small floatplane, the OSU-2 Kingfisher. He had photos of Tommy we never saw.

He also discovered, a year later, a document we never knew existed. It was an “after battle” report, marked confidential, and not likely seen by human eyes for long after the 1945 battle. It included this shock: “It is possible that the loss of the TENNESSEE spotting plane, on D-Day, may have been caused by a ship firing from Fire Support Sector 6 at extremely long range.”

The report went on to recommend our aircraft be careful to stay above the trajectory of the big shells. It suggests the Navy knew right away that a large shell had knocked Tommy’s plane apart without exploding.

***

There was much publicity about the 75th anniversary of D-Day. Celebrities, such as Tom Brokaw, have been inspired to return (after writing a best seller, “The Greatest Generation” based on our soldiers’ heroics in that historic event). Over and over we heard that the sacrifices of the invasion forces, including French resistance fighters, must never be forgotten.

One wonders about that. At the same time as all the D-Day anniversary pomp and pageantry, stories appeared about the drastic decline of visitors to hallowed Civil War sites. The Wall Street Journal reported that five major Civil War battlefields drew 3.1 million visitors last year—down from 10.2 million in 1970.

That is a disturbing sign, especially for places such as Adams County, Pennsylvania, whose economy benefits from tourism associated with the Gettysburg campaign. They used to joke that there were more re-enactors roaming around Gettysburg on weekends than there were men in the actual battle. No more.

One explanation for the decline in Civil War interest is the recent trend toward revising that history. It used to be settled history that the South seceded to form a new country, and the overwhelming numbers of their populations considered their first loyalty to their states, not a loosely constructed federal government. But recently, perversions of that history have depicted them all as racists and traitors. Thus the movement to take down Confederate monuments and portray admirable men, such as Robert E. Lee, as evil. As The Federalist put it: “If history is just another tool in the pursuit of political power, there’s not much of an impetus to get it right.”

If something as monumental as the Civil War can be forgotten, what chance does Normandy have 100 years from now?

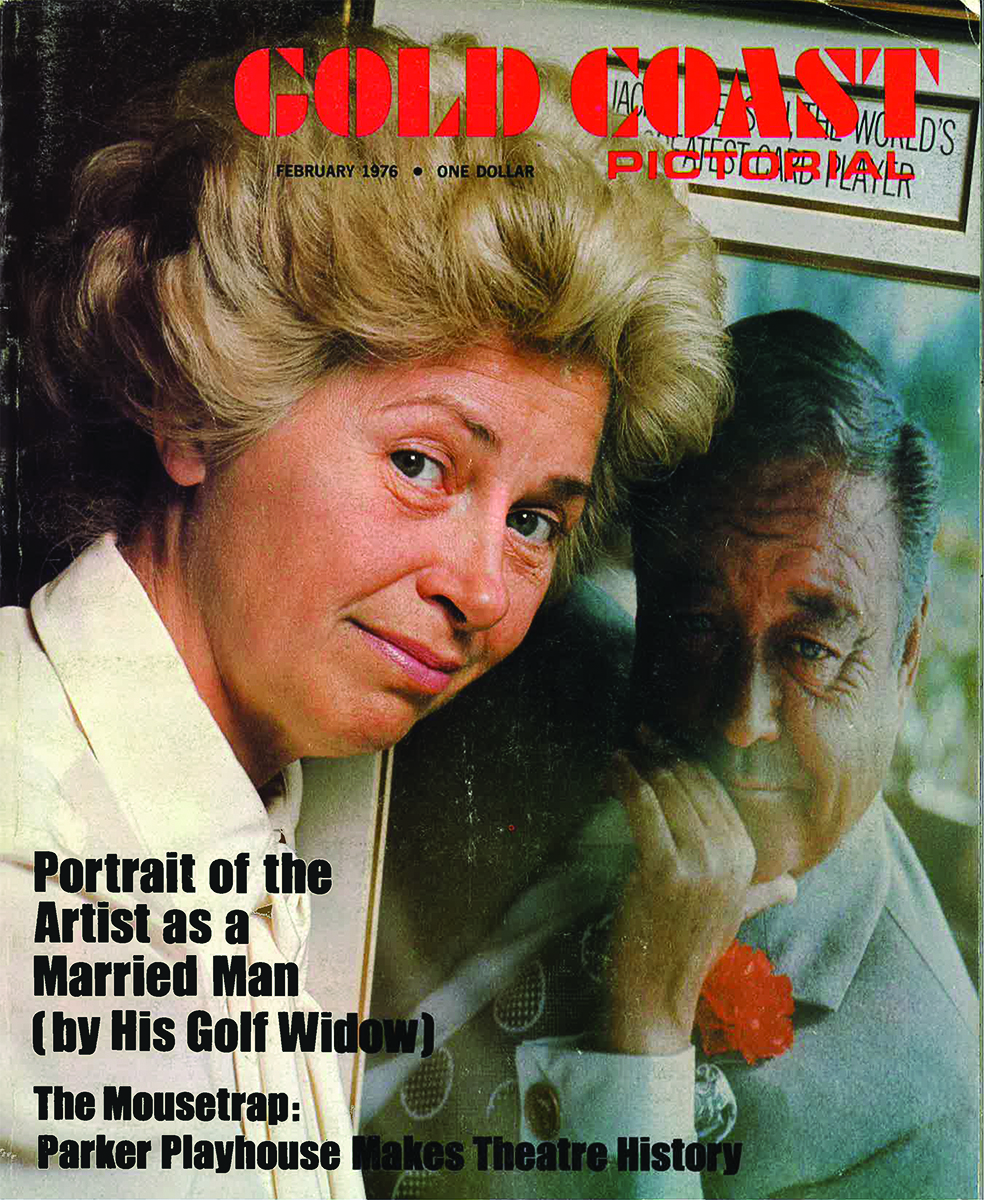

The death of Jackie Gleason’s widow, Marilyn, two weeks ago produced accounts of her long, sporadic relationship with “The Great One,” as well as praise for her unassuming behavior when married to one of the country’s most celebrated entertainers. For Gold Coast magazine, she was something else—a cover girl under unusual circumstances.

We met Gleason just before the first Inverrary Classic in 1972. Jack Drury, who handled PR for that opening tournament, may have set it up. Gleason was still living at a country club in Miami, waiting for his big new place at Inverrary to be completed. The interview was to promote his first tournament and he could not have been easier to chat with. We met at 10 a.m. in his pool room. He offered a drink. We graciously accepted.

We asked the usual questions about the upcoming tournament and then ranged to other subjects. We asked if the stories were true about his New York nightclub owner/friend Toots Shor setting him up to play pool with Willie Mosconi, the world’s best. This was back in the days when Gleason still hustled pool for extra money. Mosconi, whose face wasn’t well known, did not look formidable—a slight, pleasant guy.

“He introduced him as a friend, Mr. Shoeman, a shoe salesman from Philadelphia who liked to play pool,” Gleason said. “ He said he was good but that I could take him. I should have known something was up when 30 sports writers followed us out of the bar to the poolroom. He let me win a game or two and then opened up. I said, ‘Pal, I don’t know what your real name is, but it sure ain’t Shoeman and you ain’t no shoe salesmen from Philadelphia.”

We recall we somehow got onto the subject of sports figures and Gleason made one of his quirky observations, saying he had never met a dumb basketball player, but he knew a lot of dumb baseball players. We got a cover piece out of that interview.

Three years later Gleason married Marilyn, whom he had known since the 1950s when she was a dancer with her famous sister, June Taylor. Marilyn had moved to Florida after her husband died and became reunited with Gleason. He married her after his second divorce. Just a year later our partner Gaeton Fonzi arranged through Marilyn to interview Gleason about a subject that had long interested him—the occult, things like UFOs.

Recalling our pleasant meeting with Gleason several years earlier, we decided to accompany Fonzi on the interview, interested in seeing how Gleason would react to Gaeton’s balking, mumbling style. We arrived at the big Inverrary home early in the morning, as scheduled. Minutes later Jackie appeared, headed out to play golf.

“Boys,” he said, “I never said I’d do this. And I’m going out to play golf. I’m gonna take these guys for every cent they have.” And with that, he walked out the door. His wife was embarrassed because she had definitely set up the interview.

“That’s what it’s like being married to Jackie Gleason,” she said. Gaeton, thinking fast, said, “How 'bout if we do a story about what’s it’s like to be married to Jackie Gleason?” She thought for a full 10 seconds, then said, “OK.” It turned out to be a great interview.

She explained that although they had been recently married, she knew him years before, and her life really hadn’t changed much. She was content to be just an ordinary person married to a genius. She was insightful and articulate in a modest way. We made a memorable February 1976 cover story out of it. The cover: Marilyn Gleason holding a photo of Jackie. She remained happily married to him for the rest of his life.

Before we archive this season of St. Patrick, let us reflect upon an aspect of the Irish impact on the United States—one that is obvious, yet little commented upon. And that is how Irish names have become so common as first names that people don’t give a thought about it. First, a little history.

One of the gifts from the English to the Irish was the English language and the abandonment of the awkward, often unpronounceable old Gaelic versions of names now common in English. Gallagher, for instance, was originally O’Gallchobhairk, Kennedy was O’Cinneide and Murphy was O’Murchada.

The Irish had streamlined those names in the century before arriving in the U.S. in large numbers in the mid-1800s, driven from home by famine and a life of near slavery under British rule. Note that a mere 75 years before, Irish names were all but absent on the Declaration of Independence. There was a Lynch from South Carolina but only Charles Carroll, a planter from Maryland, is remembered. A rare Irish Catholic, he was even rarer as one the wealthiest men in the colonies.

Irish immigrants for the most part proudly clung to their names—even if some of them could barely spell them—often at a cost. “No Irish Need Apply” signs were notorious. That prejudice gradually evaporated, so much so that today those Irish last names have enjoyed unique popularity—as first names. Today, of the ten most common Irish surnames, six of them have come to enjoy some use as first names. Murphy, Kelly, Brian, Ryan, Connor and Neil all began as last names or variations of some.

Go down the list of Irish last names and those used at least occasionally as first names jump out by the dozens. Riley, Emmett, Smith, Doyle, Murray, Quinn, Carroll, Grady, Brady, Connel, Burke, Nolan, Regan, Donovan, Barry, Ward, Graham, Cullen, King, Scott. In truth, not all are exclusively Irish; a number are shared by the rest of the British Isles, notably Scotland, whose genetics are virtually identical to Ireland.

This phenomenon, which has attracted its own websites, is a fairly recent development. The very popular name Ryan was little used until the 1970s when actor Ryan O’Neal brought attention to it. Some that have gained recent currency are literally reborn. Cormac (the Gaelic equivalent of Charles) traces to a fifth-century king named Cormac. Many Irish took that name during a time when people had only one name, but when the English imposed second names on their subjects, Cormac became McCormick. Now it has gone the other way. The distinguished author Cormac McCarthy, who changed his name from Charles, has led the charge.

Although the internet covers this subject in some detail, nowhere can we find an explanation for why the popularity of Irish names. Therefore let us conjecture. We think people take Irish names for children because they don’t know it. They are simply looking for acceptable American-sounding names. They want to fit in. And Irish names tend to be short—at least compared to other European backgrounds. This is not a trend likely to spread to other ethnic strains. We are not likely to see a lot of people with first names such as Putin, DiMaggio or Brzezinski.

Any way you slice it, it is what it is, just another feather in the crowded bonnet of a nationality who came to this country in poverty and hunger, anxious to blend with the established Anglo culture, and wound up being the blender itself.

Photo via

The latest thing in running for office in Florida is to not tell the voters what you stand for. It may be the best way to win an election. As an example, we give you recently elected Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis. If you followed the governor’s successful campaign last fall, you would have only a vague idea of what he would do if elected. He seemed to be a strong supporter of President Trump, wall and all, and had nothing negative to say about outgoing Gov. Rick Scott. A rational person would, therefore, assume that he did not believe in climate change, and saw nothing wrong with his predecessor’s steps, which did little to address the problems of Lake Okeechobee pollution and the effects on the estuaries on both coasts—especially in Martin County, as well as the ongoing neglect of the Everglades.

If you thought that, you were happily wrong. The Republican governor’s first months in office find him acting much like a Democrat—at least on those issues most important to those worried about Florida’s deteriorating environment. He has shown a determination to do something about the problems of Lake Okeechobee and South Florida’s threatened water supply. To say that environmental groups, most of whom opposed his election, are surprised, is to put it mildly.

Eric Eikenberg, chief executive of the Everglades Foundation, one of the most influential environmental groups, echoes the common theme: “This is the most optimistic we have been in decades —to have a governor who made cleaning up Everglades his No. 1 priority. We could not ask for anything more. Now we have to make sure that the legislature puts money behind those priorities and we can solve this problem.”

It was not just the new governor’s actions, but the speed of them, that has generated enthusiasm from environmentalists. DeSantis lost no time in asking for the resignations of the entire South Florida Water Management District board of directors. These are the people who make the decisions that affect the water flow from Lake Okeechobee. While theoretically independent, the members are appointed by the governor and therefore reflect his views. And former Gov. Rick Scott’s views were a reversal from those before him.

Under Gov. Charlie Crist there was a plan to buy a huge parcel of land from U.S. Sugar Corporation, the Clewiston-based company that for decades has been growing sugar on land directly south of Lake Okeechobee. That land was once the headwaters of the “River of Grass” and constituted the northern reaches of the Everglades. Back in the day of Gov. Napoleon Bonaparte Broward (1905 to 1909), the land was drained with a network of canals to make it rich soil for agricultural

purposes.

Because South Florida was lightly populated at the time, turning wetlands into productive farmland had limited effect of the Everglades. But as our area became the most populous part of the state and the demand for water grew steadily, so did the damaging effects of the stunted water supply.

The problem was compounded by the loss of wetlands, which were a natural cleansing agent for fertilizer polluted runoff from all the farms. South Florida found itself in a strange situation. Lake Okeechobee was surrounded by a dike after disastrous flooding in 1928. Water built up in the lake during the rainy summers, but when the lake became dangerously high, water that nature intended to flow south into the Everglades was discharged through canals east and west. Areas that did not need water, such as the Stuart area, got too much polluted water, while the Everglades to the south did not get enough.

The U.S. Sugar land acquisition plan would enhance the natural flow of water, in effect restoring a crucial part of The Everglades. But under Gov. Scott, the plan to purchase land died. A spokesman for U.S. Sugar said it decided not to sell after the state changed its mind about buying the land. But the truth is Gov. Scott nixed the deal by appointing his own people to the Water Management District.

In recent years, the situation became disastrous, at least for Martin County, as polluted water from the lake merged with seawater, producing an algae buildup, which killed sea life in an area where the economy depends on its reputation as a water wonderland. Gov. Scott’s administration worsened the problem by replacing management of the South Florida Water Management District with directors who favored the polluting agricultural interests over environmental concerns. Scott was obsessed with growth and new jobs. He showed little interest in people already living here. Eight years were wasted, and those years finally saw decades of neglect have their effect. In addition to pollution on both coasts opposite the lake, rising sea levels have been creeping inland, under our shallow crust of soil, encroaching on freshwater supplies for millions of people in Palm Beach, Broward and Dade counties.

Now all this history has been widely publicized. It is hard to live in South Florida without understanding at least the basics of the water problem. But one might think Gov. DeSantis, from far up in Daytona Beach, would not be acutely aware of the situation.

Wrong. So far.

Photo via

The college traced its roots to 1809 when it began as a small Catholic boarding school for middle-class girls in a remote and peaceful part of Maryland. A Washington newspaper once described it as “the kind of setting Hollywood used to seek out for inspirational movies.” The nearest town was Emmitsburg, and it lay in a valley bordering the Catoctin Mountain range. Except for a dramatic few weeks 50 years later, it has remained remote and peaceful. The summer of 1863 was the exception; when the great Civil War battle of Gettysburg took place just 10 miles to the north, barely inside the Pennsylvania border. Union troops camped on the school grounds en route to the fight, and some Confederate detachments also passed near the campus. The nuns who ran the college cared for both Union and Confederate wounded after the bloody three-day battle.

One hundred and fifty-six years later the school is still there, at least the bucolic grounds, with stately red brick buildings. But it is no longer a college. Saint Joseph’s College closed in 1973 and the grounds are now the National Emergency Training Center. Saint Joseph’s, just down the road from the still going Mount Saint Mary’s, was a victim of its small size (about 600 girls at its peak), the growing unpopularity of one-sex colleges and the declining numbers of free teachers, i.e. the Daughters of Charity (the ones with the sailboat hats).

The college may be gone, but many of the women who attended it are still around. Considering how many of them hated the strict rules (in the late ’50s, girls were expelled for simply attending parties where alcohol was served), the loyalty of the alumnae is extraordinary. The campus reunions are fewer, but they have been so well attended over the decades that they used to say if a classmate did not show up, she had likely gone above.

And thus we traveled last month across the state to Sarasota, where the Saint Joseph’s class of 1961 has been holding informal reunions for close to 10 years. Sarasota is the site because several of the women are retired there, or have winter homes in nearby Gulf Coast cities. Others plan Florida vacations around the event. Although the numbers have declined as some women, and especially the husbands, have died. They still manage to draw a dozen women and assorted relatives and friends.

For those of us still moving, it is an opportunity to check out one of the state’s most distinctive communities, long noted as an arts center, and recently facing the usual problems of growth, i.e. redevelopment vs. overbuilding—resulting in a vibrant downtown compromised by too many people trying to move around in a small area.

Let’s start with the traffic—the root of the problem is what makes Sarasota such a beautiful spot. The large and magnificent bay provides wonderful sites for single homes and high-rise residences. But unlike the east coast, where most communities have access to the Atlantic beaches every few miles, the Gulf of Mexico beaches are reachable by a few causeways that are miles apart. The results are traffic jams both morning and afternoon. We are talking about serious holdups, lines of crawling vehicles sometimes a mile long. And the roads leading to those bottlenecks are equally congested. Aside from I-75, which lies farther out of town than I-95 does from east coast communities, the main road up and down the coast is U.S. 41. Compared to U.S. 1 on our side, it is frustratingly slow. A friend who met us for lunch in downtown checked his route guidance from his home and expected an 18-minute drive. But it took a full half hour due to traffic on U.S. 41.

Sarasota’s downtown is a bustling and attractive place, filled with restaurants and shops. The main shopping street, oddly enough, is called Main Street, and the shoppers and diners, reflecting the heavy retirement community, are conspicuously older than people on Fort Lauderdale’s Las Olas Boulevard. The retail presence is also obviously stronger and more varied with an emphasis on artsy stores. The downtown directory lists a dozen galleries, and not all are on the main drag. The commercial district extends to cross streets, which feature antique stores and a number of thrift stores. The latter is especially appealing to the Saint Joseph’s alumnae who reserve at least a day for touring those outlets.

The number of galleries and art-related stores reflects Sarasota’s long history as an art center. The Ringling, the State Museum of Florida, goes back nearly a century, to when the circus family first brought its love of art and antiques to the city. The Ringling College of Art and Design opened in 1931 and has a national reputation. All this is valued by its residents, both full time and winter, but they all deplore the building boom that has seen too many skyscrapers, too fast, too tall, too close together.

Sound familiar?

Judging by the media tributes that accompanied the death of President George H.W. Bush in December, we buried a near saint. Perhaps he was, compared to some of the figures who succeeded him in the Oval Office, but there was also a side to the senior Bush that received almost no mention in his many obituaries.

An exception was Tim Weiner, writing in The Washington Post, who hinted at what some researchers have long suspected—that Bush’s connections to the American intelligence community went far beyond his brief term as CIA director in the 1970s. Wrote Weiner: “He was the only president who ever ran the agency and the last president who truly believed in its Cold War code: Admit nothing, deny everything.”

That seemed like an odd comment, for the senior Bush served as CIA director for just a year. That is a puzzling short time to develop such an intense commitment to the agency. That is, unless Weiner, a Pulitzer Prize winner and authority on the FBI and intelligence operations, knew that the ex-president may have been a CIA asset long before he took the top job. President Bush appears to have been connected to our intelligence apparatus at crucial and controversial times in its history. There was even a book written about his clandestine past. It contradicts the portrait of Bush as an example of a kinder, gentler political era.

It goes back to 1953 before Bush became politically active. He formed Zapata Oil with a partner who had recently resigned from the CIA. Oddly enough, that partner later returned to the CIA during the period of anti-Castro activity in the 1960s. Researchers have discovered documents indicating a subsidiary of Zapata Oil used offshore drilling facilities in the Caribbean as a listening post to monitor Cuban activities. Zapata Oil may have been a legitimate oil exploration company, but it also appears to have been a CIA front. More than a few companies active in Latin America were.

Here’s where it gets interesting. Declassified government files led to the discovery in July 1988 that on Nov. 23, 1963—the day after President Kennedy was assassinated—“George Bush of the CIA” was given an oral briefing by the FBI. Now, what was that all about? When asked at the time, Bush first joked it off. Then the CIA suggested it was a different George Bush. There was another George Bush in the CIA at the time, but he was a low-level analyst and signed an affidavit saying there was no way he ever had an FBI briefing. President Bush’s office said it would not dignify the report with further comment, and to the best of our knowledge never made one these last 30 years. Admit nothing. Deny everything.

This snippet of history interests us because of Gold Coast magazine’s long interest in the Kennedy assassination, and the fact that our former partner, Gaeton Fonzi, has gone down in history as the author of one of the most important books on the subject. It was a book that began as two long articles in our magazine in 1979. “The Last Investigation” was the result of three frustrating years Fonzi spent as a Florida-based investigator for two government committees that reopened the investigation into Kennedy’s murder in the mid-1970s.

Fonzi was initially hired by Pennsylvania Sen. Richard Schweiker, who recalled articles Fonzi had written in the 1960s for Philadelphia Magazine. One of them was an interview with Arlen Specter, the man who came up with the “magic” bullet theory to show how a lone gunman could have killed the president. Specter astounded Fonzi by stumbling in trying to explain his own theory. By 1975, Schweiker, having studied Lee Harvey Oswald’s strange defection to Russia and mysterious return, was convinced that the accused assassin had “the fingerprints of intelligence all over him.” He also thought a close look at anti-Castro figures operating in South Florida could be productive.

It sure was. Fonzi discovered that a prominent Cuban anti-Castro leader in Miami had seen his main CIA contact in the company of Oswald in Dallas just months before the assassination. It reinforced what others, including Sen. Schweiker, had suspected—that rather than being “a lone nut,” Oswald was a CIA operative who had been set up. A “useful idiot” to use a favorite CIA phrase. By then Fonzi was working for a second congressional committee, the House Select Committee on Assassinations.

He was excited in 1976 when Richard Sprague, a brilliant prosecutor who Fonzi knew well from Philadelphia, was hired by Schweiker to head the committee. Fonzi thought if anybody could solve this crime, it was Sprague. Fonzi was anxious to follow up on his Oswald CIA connection. But Sprague’s time in Washington was short. Sprague was literally forced out of his job after some indiscretions in his past were publicized way out of proportion. It turned out Schweiker’s enthusiasm for solving the Kennedy assassination was not shared by other government officials. When congressmen on the committee, who now appear to have been CIA friendly, threatened to shut down the whole investigation because of Sprague, he resigned.

He later said his problems in Washington began when he refused to sign an oath of secrecy requested by the CIA. “My problems in Washington began when I knocked on the door marked CIA,” Sprague said. His replacement was G. Robert Blakey, a well-intentioned man with impressive credentials (Notre Dame law professor) but one who did not believe the CIA would lie to him or his committee. He preferred to concentrate on organized crime figures as possible assassins, and there were some mob connections to be explored. He later regretted his naiveté. The bottom line was that the HSCA investigation, rather than being thorough and conclusive, was rushed under budget pressures and vague in its final report. It said there was evidence of a conspiracy, but gave you multiple-choice options.

Fonzi, who had constant frustration trying to work with shadowy CIA figures in South Florida, was depressed. His magazine articles were in effect a dissenting opinion. We might add that we saw all this up close; Fonzi sometimes worked out of the Gold Coast magazine office (he was still contributing occasionally to the magazine) and sometimes used our phones. We never billed the government.

What does all this have to do with the late President Bush? Timing. Bush became CIA director in January 1976. Richard Sprague was hired to run the JFK investigation in October 1976. Although Sprague did not resign until March 1977, his problems with the CIA began soon after he was hired, and came to a head in early January 1977 when Bush was still CIA director. The obvious question: what did President Bush know about the CIA’s pressure to oust Sprague? As CIA boss, he certainly should have known something. And did he have anything to do with a decision, which turned out to have wrecked the last serious attempt to solve the murder of a president?

When Fonzi wrote his magazine articles in 1979, the strange FBI memo naming George Bush in connection with the Kennedy assassination briefing was not known. Fonzi did not make any reference to the above timing, but when his articles became a book in 1993, he included the mysterious memo. He did not, however, link Sprague’s downfall to the timing of Bush being CIA director.

By then Bush was president, and questions about the Kennedy assassination had greatly intensified. Jim Garrison’s book that inspired Oliver Stone’s 1991 movie “JFK” had been published. We asked Fonzi at the time why Bush would have denied the 1963 FBI memo, even going to the extent of the CIA saying it was a different man with the same name. Fonzi replied that in 1988 Bush was running for president, and any suggestion of a relationship to the Kennedy assassination, no matter how remote, could have been devastating to his election chances.

Fonzi died in 2012. If he were alive today, we think he would reflect on the Richard Sprague episode in 1977 with great interest. What, if anything, President Bush’s role was in that event may never be known. He took that information with him.

Admit nothing, deny everything. To death do us part.

***

As this article was being prepared, there came an announcement that members of the Kennedy and Martin Luther King families were among those who signed a petition asking Congress to reopen the investigations of the murders of President Kennedy, his brother Robert, Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X. The list of those signing the petition is a veritable who’s who of prominent figures (those still alive) that have long challenged the official government versions of the JFK assassination. Notable among them: G. Robert Blakey, now in his 80s, is the same man who thought he could trust the CIA when he took over as head of the House Select Committee on Assassinations in 1977, and whose committee issued a report saying JFK’s death was a conspiracy but left us guessing by whom. Stay tuned.

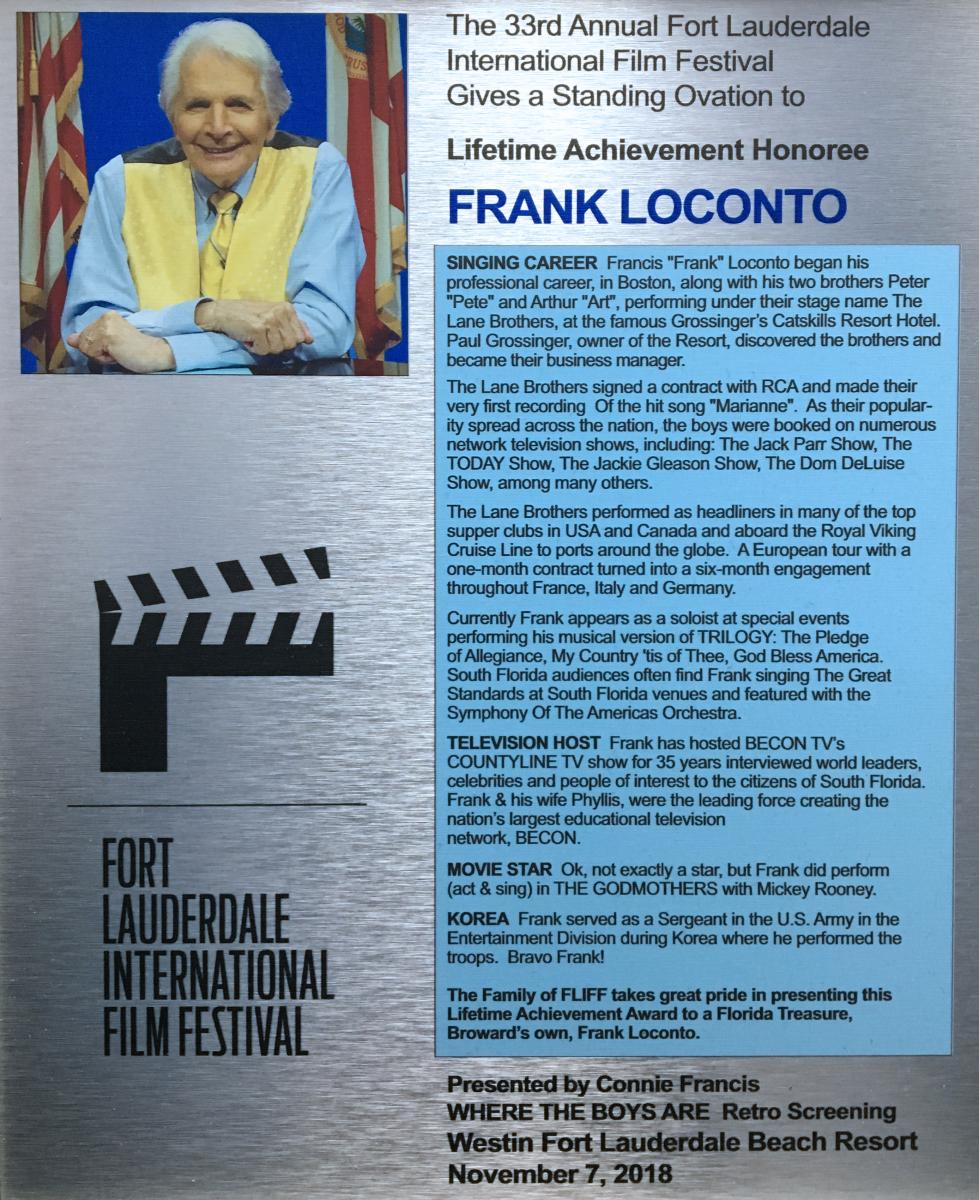

Longtime Fort Lauderdale entertainer and broadcaster Frank Loconto received a well-deserved tribute last fall when he was honored with a lifetime achievement award at the 33rd annual Fort Lauderdale International Film Festival dinner. It was presented by his friend of many years, Connie Francis, a co-star of “Where the Boys Are,” the 1960 film that helped put Fort Lauderdale on the map as a spring break destination. The plaque shown above details his interesting career, beginning with singing with the Lane Brothers in Boston in 1955. He still performs as a soloist at South Florida events.

He launched a second career in broadcasting, and for 35 years has hosted Becon TV’s “Countyline” show, interviewing celebrities and leaders far and wide. Wearing his trademark vests, he calls upon his experiences and contacts of more than 50 years in South Florida, with an interviewing style that is informal, yet always interesting.

For several years Frank sang on Sunday afternoons at Mangos restaurant on Las Olas Boulevard, sometimes joined by former Mangos owner John Day, who also began his career as an entertainer. The restaurant was sold and has been closed for renovations. It is scheduled to reopen very soon as Piazza Italia, a dramatic change of format and cuisine. Frank expects to resume his Sunday afternoon performances under the new ownership.

We made a New Year’s resolution to not waste this valuable space with anything as banal as critiquing sports uniforms. But that was last year’s resolution, which we proudly kept, and this is a brand-new year and some of the 2018 violations of the uniforms code of athletic duds have been so egregious that we must go on record. This is particularly motivated by the results of recent football bowl games, and the coaching shakeups of the last month, all of which relate to some awful uniform decisions by persons who should know better. Please do not think this is an opaque subject. Check the internet. Sports uniforms rank second in internet searches only to President Trump’s sex life.

Let us start with the bowl games. History will show that Notre Dame got blown out by Clemson on Dec. 29, but the truth is they lost that game on Nov. 17—the day they played Syracuse in Yankee Stadium. They won easily that day, 36-3, but in a larger sense, they lost. For that was the day they decided to honor the New York Yankees by wearing the football equivalent of the Yankees’ classic pinstripes. They may make great baseball suits, but they looked awful in football, especially to the 40 million New York Irish fans who turned out with their families to see the Irish in their traditional unadorned gold helmets and pants.

Those fans were crushed, and so was God, who takes Notre Dame football personally. God was already upset a couple of years ago when Notre Dame came out in bilious, green outfits, looking like praying mantises for a game against somebody or other. God was further annoyed earlier this season when ND wore their novelty green jerseys— except the green was not a vibrant Kelly green, but rather an insipid avocado, made even uglier by dark numbers. God vowed to punish them, and it happened against Clemson. There was no Irish luck on replay calls that day. Had they not sinned in New York, they still might not have beaten a very good Clemson team, but at least they would have covered.

Closer to home, the Dolphins fired their coach after several disastrous seasons of wearing teal, a very feminine color, as opposed to aqua green, which might be considered ladylike, except the original Dolphins studs went undefeated with that shade. The current Dolphins made it worse by wearing teal pants with white jerseys and helmets. No symmetry there. Dark pants (think Washington Redskins, Chicago Bears) are only acceptable with dark helmets and white jerseys.

Even worse was the University of Miami where coach Mark Richt, a classy young talent, had no choice but to resign after losing his mind and letting the Hurricanes wear black uniforms in 2017. One of the most visible logos in sports, the orange and green “U” on the team’s white helmets was totally lost against the black helmets. The team never recovered from that diabolical uniform. Back in Howard Schnellenberger's championship days at Miami, the Hurricanes had a great look. When he started a new program at Florida Atlantic, he patterned the uniforms after UM and took the program big time in a hurry. Alas, in recent years FAU has changed its uniforms so many times you don’t even know what the school colors are. They dressed to lose and did.

There are numerous examples of teams with no sense of tradition, but let us replay to the positive. It was no accident that the four teams in the college playoffs all have a strong sense of their identity—at least on the football field. Alabama has almost never broken from its successful look, even with numbers on their helmets instead of a garish logo. Notre Dame, despite the aforementioned crimes, usually looks like it did back in the era of Johnny Lujack in the 1940s. We have not studied Clemson as much, but they seem to stick to a predictably orangy style although we are not fond of solid orange uniforms, or all any color for that matter. Except for white. Oklahoma looks very much like the uncomplicated uniforms it wore when we saw the Sooners play Texas in the Cotton Bowl in 1959.

Speaking of Texas, they are an iconic pacesetter, either in all white, with a minimum of striping, which looks great, or switching to burnt orange jerseys at home. They have always worn horny helmets. That elegant taste was rewarded as they handled Georgia, who also dresses quite well, in the Sugar Bowl. It was a case of good dressing losing to better.

This is being written with the championship game a few days away. Based on history, we must pick Alabama, especially if they wear their crimson home jerseys. On the other hand, if Clemson wears orange jerseys and white britches, we respect their chances. Especially if they score more points.