Remembering the Big One

New Orleans: Mardi Gras, Bourbon Street, Cajun cuisine, ancient streetcars, Tulane, Katrina, one of the more pleasing uniforms in the National Football League and old southern folks who sound more like Yankees. These are the things that come to mind when you hear this city mentioned. Add to that list one more—The National World War II Museum.

We must join the embarrassed regiments of those who never knew this remarkable historic treasure existed, despite the fact that it has become one of the city's biggest tourist draws.

The buildings themselves are impressive and located in a redeveloped section in the heart of downtown. The museum is split into several sections in connected buildings, dividing the war into theaters, Europe and the Pacific, just the way it was. Hundreds of the primary weapons of both sides are displayed, along with films showing them in use. If you have never been run over by a 56-ton German Tiger tank, one of the films shown in an IMAX theater will suggest the thrill. Seats vibrate and sound booms from every angle when the Navy twin 40s anti-aircraft guns open up on a Japanese kamikaze bomber. You see through the eyes of the landing officer as he waves his paddles to guide a Douglas Dauntless dive bomber home to the deck, and almost feel you are one of the sailors racing to the aid of a pilot who misses his landing and careens toward the edge of the flight deck.

We spent about four hours in the museum, but such is its scope that we missed the one exhibit I would most like to have seen. I spent time in the Navy aviation pavilion, hoping to see some footage on the airplane in which my cousin, Lt. j.g. Thomas F. McCormick (pictured below) lost his life at Iwo Jima. He was a reconnaissance pilot who flew a catapulted floatplane off the Battleship USS Tennessee. The plane was the Chance Vought Kingfisher, probably built at the Naval aircraft factory at the Navy Yard in Philadelphia, where Tommy McCormick spent much of his life and played football at what is now La Salle University.

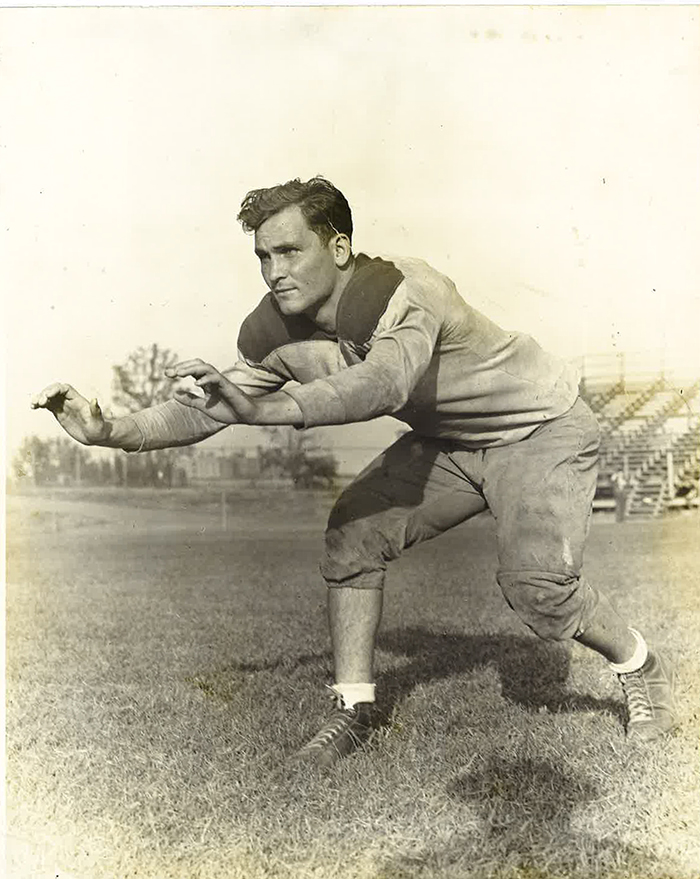

I was just old enough to remember him vividly when he came home after his first cruise at Christmas in 1944. The Tennessee had just participated in the invasion of the Philippines. He was a great looking guy, dark-haired and big. My brother, three years younger, does not recall him. Tommy died at Iwo Jima two months later, and only in recent years did we learn he had already survived one close call when his plane crashed while making a tricky water landing next to the big battleship. He and his radioman escaped, but the plane was lost. We also learned—through the kindness of Paul Dawson at the USS Tennessee Museum in Huntsville, Tennessee—that Tommy was probably shot down by friendly fire. We knew that there was no explosion when suddenly his plane broke in half. Observers on his ship reported two airplanes might have collided.

Paul Dawson, whose father had been the ship's photographer and actually knew my cousin, discovered an after-battle report, which probably had not been seen by human eyes for 60 years. For good reason it was marked "confidential" at the time. It suggested that a high-angle shell hit his plane, which flew at low altitude in order to observe the effect of our bombardment on Japanese positions. The shell never exploded as it went through the little Kingfisher like tissue paper. It cautioned against such possibilities in the future.

What we missed at the museum was a film that included the most famous Kingfisher event of the war. It also involved the most famous submarine of the war. The USS Tang sank more enemy ships than any other sub. It also took part in an amazing rescue operation with a Kingfisher floatplane in April 1944 off the Japanese island base of Truk (now known as Chuuk). The floatplane, piloted by Lt. j.g. John A. Burns, flew off from the battleship North Carolina. It had picked up six downed airmen in the Truk Lagoon during a major attack. Men were sitting on the wings and fuselage. It was so overloaded and damaged by rough seas that it could not take off. Burns, under enemy fire from the shore, taxied his plane to the Tang, which picked up all the men and then sank the damaged aircraft before escaping.

Burns received the Navy Cross for his heroics. Coincidentally, he was also from the Philadelphia area. He and my cousin were the same age and had enlisted about the same time. It is possible they knew each other. We will never know. On Feb. 26, 1945, exactly one week after the morning Tommy McCormick was killed in the Battle of Iwo Jima, the Philadelphia papers reported that war hero John Burns had died in a crash landing at Naval Air Station Oceana in Virginia.

Tommy McCormick at La Salle College in 1941

Main image via