Downtown Development and Legacy of Bill Farkas

Our dinner party was driving from east Las Olas, at the top of the islands, to meet us at the Riverside Hotel. Ordinarily, that nine-block trip takes about five minutes, sometimes a little longer on busy nights. When the party was 15-minutes late, we called to find the problem. Extremely heavy traffic, we were told. Another 15 minutes passed, another call. Traffic not moving at all on Las Olas. It was 45 minutes before our party arrived, and we were suspicious when they said at a traffic light they were three cycles when nobody moved. The problem, as we now know it as gridlock, was cars coming from a few side streets, getting stuck in the middle of the intersection, blocking the street so nobody could move. We thought they were exaggerating to cover their lateness. Until we drove back the same Las Olas route. It was still bumper to bumper, stopped cold, all the way for 10 blocks. Welcome to the future.

We had just read a Sun Sentinel editorial lamenting the influence of lobbyists on the government bodies who vote on growth issues. These are people who make a living representing developers, influencing and making decisions that often favor the developers who hire them, often in the face of strong opposition from neighbors. They usually say how the latest monster building is a great boon to its neighborhood, and ignore the increasing burden on the city's infrastructure. Fort Lauderdale has its best neighborhoods on the east side of town, and every increase in downtown traffic hurts the quality of life in these neighborhoods.

Those who still read the Sun-Sentinel had to be amused by a recent article in which city commissioners and others who are allowing increasing big buildings justified their behavior. One commissioner was quoted as saying "people want to come here," as if they had a moral obligation to welcome newcomers. Quite a contrast from the attitude on newcomers on a national scale. Imagine Donald Trump welcoming immigrants from all over the world because they want to come here.

When we read about the downtown growth of recent years, our thoughts drift back to Bill Farkas. Farkas became Downtown Development Director in the mid-1970s. He took the job when downtown's highest building was Landmark Bank, nine stories tall. Much of the downtown was run down. Las Olas was quiet. A previous development director had gotten the city in a mess by illegally razing older blocks. Worse, Farkas suffered the humiliation of not even being told that his biggest employer, Burdines was moving its big department store to the new Galleria Mall, where it is now Macy's.

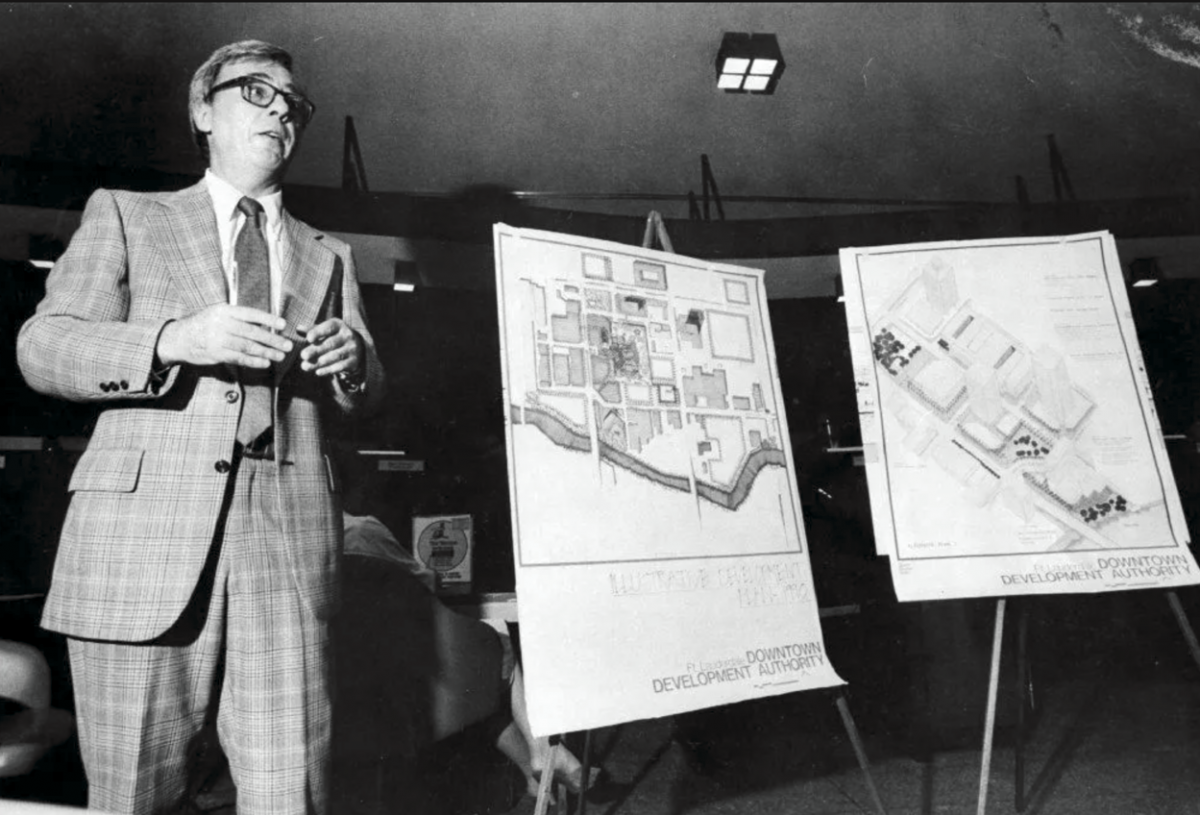

Bill Farkas was popular in a role that often involved controversial decisions.

Farkas' first win was converting the former Burdines location to a government center, holding a base of workers on a site that featured the community leadership. Progress came slowly. At one point, tennis courts were built just off Las Olas, giving the impression that something was happening. Then came a few new buildings, along with some upgrading of the stores on Las Olas. Farkas, dealing with conflicting interests, developed a reputation for tact and fairness. His upbeat and winning personality made him one of the most popular public figures of his time. Over the next 15 years, he brought downtown attractions, including the NSU Center for the Arts, a new library, the Discovery Center, and facilities for Broward College and Florida Atlantic University. By the time he left as development director, development was noticeable. Farkas' crowning achievement was yet to come. His reputation for competence earned him the job of building the ambitious Broward Center for the Arts on an artificial mound on Las Olas west of Andrews Ave. It spurred the renewal of that depressed neighborhood. Wayne Huizenga's Blockbuster, located nearby, and a whole block of restaurants appeared just west of the FEC railroad tracks. Wally Brewer's Olde Towne Chop House and the Tarpon Bend restaurant across the street became hot spots.

By 2000, his success in redevelopment was producing a reaction from residents concerned that it was too many high rises, too fast. There is no record of his commenting on the subject, but his work over the next decade is telling. He had lived in Miami Beach, and he took over leadership of preserving historic buildings in that neighborhood. By the time of his death in 2019, one has to think that the accelerating redevelopment in Fort Lauderdale may have him wondering if he had been responsible for dramatically altering the city's ambiance. On the other hand, there are worse legacies than being too successful.

Downtown

This Comment had been Posted by Laz

long ago and far away