Making bad words bloody good

Our latest project, with the working title "All The President's Women," will be groundbreaking for its use of language. We plan to set a record for dirty words. That is going to be a challenge, for in the last few years words we would not use outside of locker rooms—and men’s locker rooms at that—have become commonplace in the media, including national television.

Not long ago certain expressions for bodily functions, or places where they normally occurred, were considered vulgar. You bloody wouldn’t use them when being introduced to the queen. But in recent years they have become bloody common, almost to the point that they are losing their shock value.

Which brings us to the word “bloody” and the memories of the best teacher we ever had. His name was Dan Rodden. He taught English at La Salle and began every course by spending the first two weeks dissecting word by bloody word a definition of art. “Art is intellectual recreation achieved through the contemplation of order.”

It would take us two weeks to repeat those lectures, so let’s move on. Dan Rodden ran our college theater, which was strong in musicals and at one time had quite a nice little reputation in Philadelphia. After rehearsals, he went drinking with his student performers, which meant he sometimes felt and looked bloody awful in the morning. It was a mood he carried into the classroom. With that being said, he was a delightful teacher and the man who first explained to us that when vulgar language becomes too common, it loses its shock value.

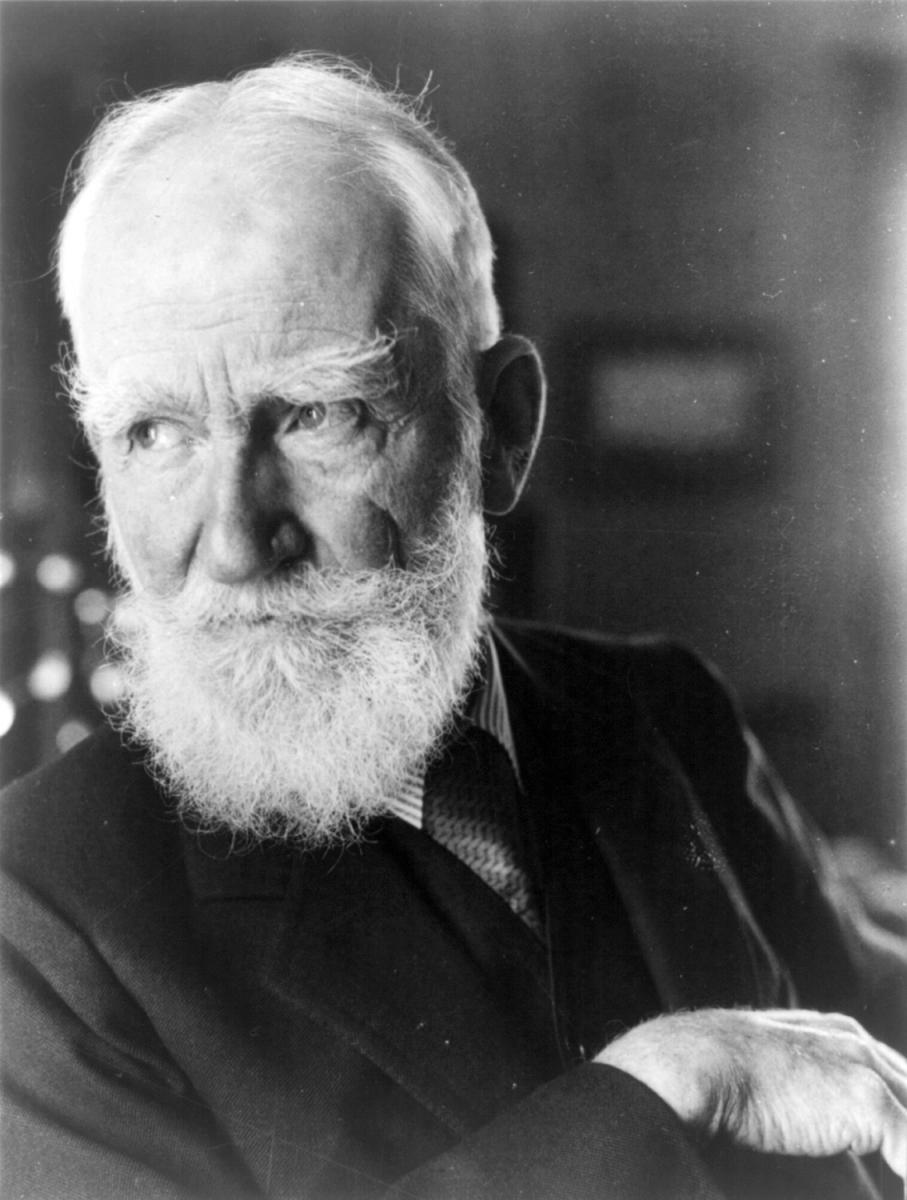

In teaching a course on theater, he mentioned a George Bernard Shaw play. We forget which one, but it was probably “Pygmalion,” which decades later inspired the musical “My Fair Lady.” In it, a character used the word “bloody.” Rodden pointed out that at the time (1913) the word was never used in polite British society. Rodden said this was like using the word “s**t” in our time. Our time, of course, being the1950s. It shocked the British audiences and helped mold Shaw’s image as a literary rebel.

That revelation amused us, as it still does most people in the U.S. Here, the word is regarded as just another example of British slangish, like “bloke” or “mate.“ But it still is regarded in Britain and parts of Australia as rather lowlife and used only by the culturally inadequate.

And so it may be with some of the crude words, now emanating from Washington sources that are increasingly polluting our national discourse on events, and in venues that deserve more refined expression. Which is why we need to come up with all the bad words we can think of and put them in a single historical source. And use them while they’re still bloody good and dirty.

Image via