The Southern Reality

Now that the storm is over it is time to return to priority items, namely rewriting American history.

Aside from the fact that so much of it is plain silly, the disturbing fact about the controversy over Confederate memorials is that much of what has been written and broadcast reflects a one-sided understanding of that cataclysmic event in American history—the Civil War.

It has bothered us almost since it happened that the murder of President Kennedy in 1963 appears to be going down in history as the work of a lone nut, whereas the evidence is mounting that JFK was killed by a conspiracy involving the highest levels of our government. However, as new information surfaces year by year, there remains a chance that the truth may prevail.

Which makes the Civil War situation more troubling. The history of that conflict has long been written; the economic causes of the conflict and motives of the combatants should not be in dispute 150 years later. And yet they are. You see Robert E. Lee, one of the most admirable men in our history, is described as a “traitor.” And southern generals, and by extension all the poor grunts who fought and died under them, are said to have fought to preserve slavery.

Even reporters covering various memorial protests seem weak on the details of the Civil War. The Miami Herald, in its front page report of the latest Hollywood street debate, described John Bell Hood, one of the Confederate generals who has a street named after him, as “a commander at Gettysburg.” Technically correct. Hood, serving under James Longstreet, was one of nine division commanders in Robert E. Lee’s army. Hood had good reason to remember Gettysburg. He lost the use of an arm there. Transferred to the western theater, he lost a leg at Chickamauga. But history remembers him for a more significant loss. He took over command from Gen. Joseph Johnston of the Confederate army defending Atlanta in 1864. As bold as Johnston was cautious, Hood made some rash decisions. They led to the loss of his entire command, the only force standing in the way of Sherman’s infamous “March to the Sea.”

That’s just a mini example of shallow reporting on this subject. The main problem is that much of the public accepts the idea that southern generals and their men fought to enslave other men. Some historians cite the fact that southern state legislatures, in voting to secede, cited slavery as a reason. But those legislatures, dominated then as today by commercial interests, did not fight the battles and die in great numbers. Those common soldiers fought for their states, right or wrong, and considered themselves patriots rather than traitors.

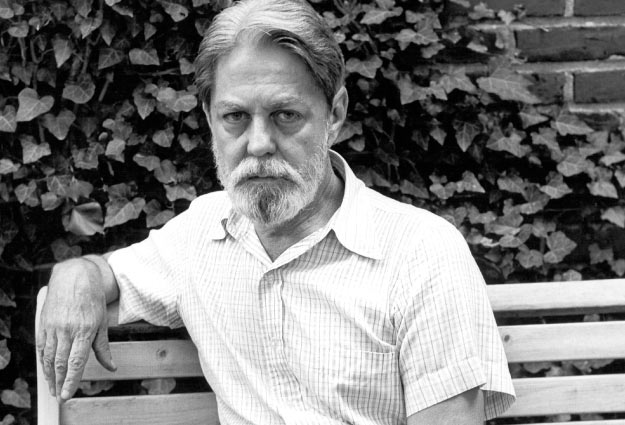

Shelby Foote, (pictured above) who spent 20 years of his life writing a great three-volume history of the Civil War, has put the matter in perspective:

“People who say that slavery had nothing to do with the war are just as wrong as people who say slavery had everything to do with the war. That was a very complicated civic thing.” In the same interview, Foote added in his infectious Mississippi drawl: “Believe me, no soldier on either side gave a damn about the slaves. They were fightin’ for other reasons entirely in their minds. Southerners thought they were fightin’ the second American revolution. Northerners thought they were fightin’ to hold the union together. And that held true throughout the whole war.”

Southern military leaders were considered anything but traitors in their own land. Just the opposite. Gen. George Thomas was shunned by his own Virginia family because he was the rare southern-bred officer who stayed with the union. Gen. John Pemberton was born in Philadelphia, but married a southern woman and served much time in the south. His two brothers fought for the Union and he was a pariah when he moved back to Philadelphia after he had held high rank in the Confederate army.

It is understandable that years after it ended, the south honored men it regarded as heroes. The same held true for the north. Monuments to southern generals were no more endorsements of slavery than monuments to northern men were considered thanks for freeing the slaves.

Some of the very generals whose history is being removed understood this better than anyone. The Union’s Ulysses Grant and Confederate James Longstreet served together before the war and remained friends afterward. Robert E. Lee had a cordial relationship with George Meade, the man who beat him at Gettysburg. A full quarter of a century after the war ended, Confederate Joseph Johnston died of pneumonia contracted when he stood outside on a cold February day while serving as a pallbearer at the New York City funeral of his old adversary, William Tecumseh Sherman.

That was the reality of the time. The monument destroyers should remember that—as if they knew it in the first place.

Image via