NSU—Monument To Abraham Fischler

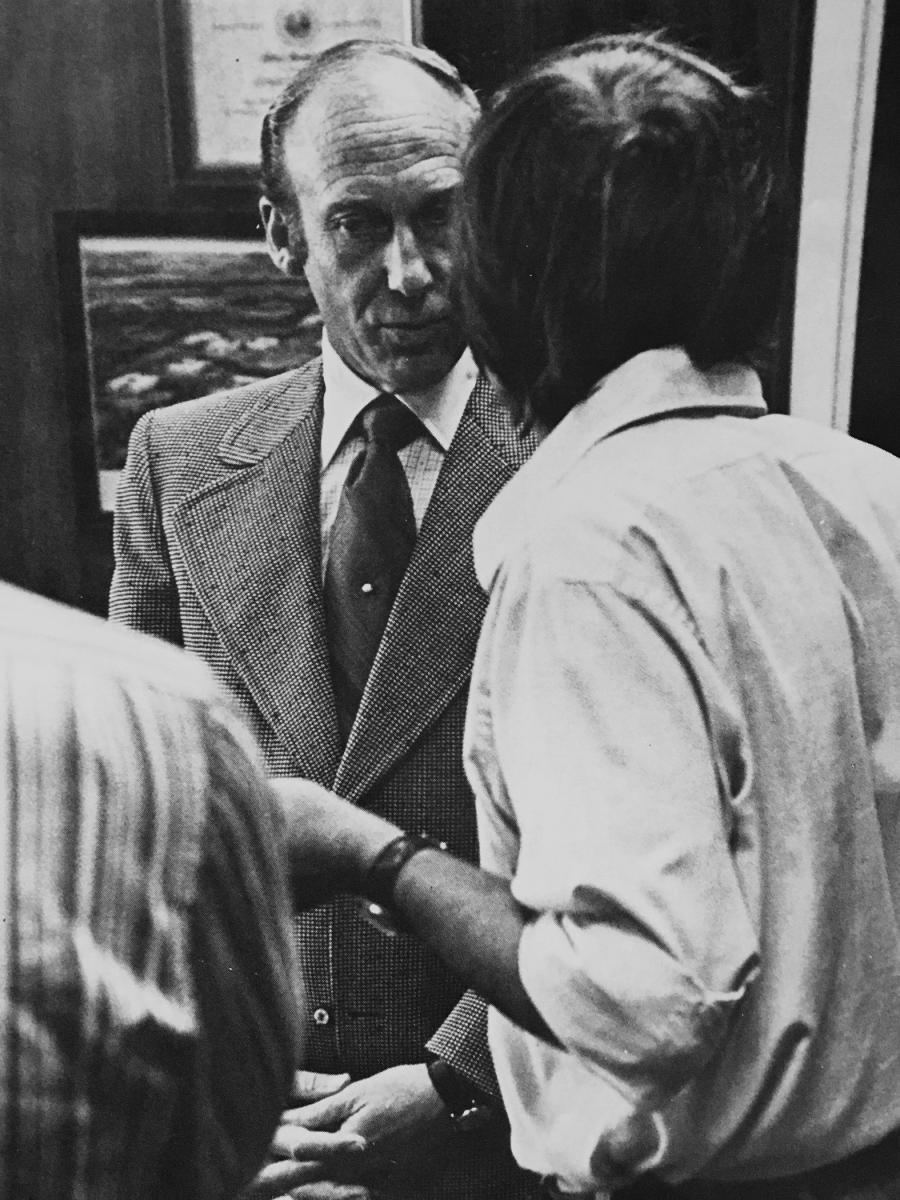

The weight of a compliment is directly proportional to the weight of the person giving it. Thus one of the most valued comments in our 56 years in the magazine business came from the late Dr. Abraham Fischler. We bumped into him at a luncheon a few years back. It was probably for Nova Southeastern University.

“You are one of the few guys in your business I respect,” he said. We had known the man casually from almost his first years at Nova in the early 1970s, but that accolade came as a very pleasant surprise. And we were pretty sure what motivated it. It wasn’t the long 1973 piece we wrote for Gold Coast magazine, in which Dr. Fischler was already being credited with saving the young university from bankruptcy. More likely he recalled columns we wrote for the Hollywood Sun-Tattler in the late 1980s. By then Nova had a growing law school, had pioneered the off-campus degree program, which was widely imitated, and had begun developing medical programs, and other curricula that filled a community need. A school that had been viewed as an educational joke was turning into a real university.

But Dr. Fischler was upset that some of the new programs were being duplicated just across the road from Nova’s growing campus, at the satellite campus of Florida Atlantic University. As one who had been the key player in achieving the rare feat of making a new private university succeed in the 20th century, he naturally did not welcome such intimate competition from a state- supported institution.

We quoted him as saying there was no “educational” need for such state programs, at least not in South Florida, but there was an obvious “political” motive. Local legislators wanted to show the voters that they were doing something in Tallahassee. The Sun-Tattler, which expired in 1989, was little read outside of Hollywood. But it was an excellent little paper, and it was one of the few voices calling public attention to Nova’s legitimate complaint, and we gather our stuff had some influence. At least it mattered to Abe Fischler, who remembered it more than 20 years later.

Dr. Fischler died in April at 89, and to understand the importance of his luncheon compliment, one needs an appreciation of what Dr. Fischler achieved in his 50 years in South Florida. Among the dozens of people who contributed much to our economic and cultural development over the years, it is hard to think of anyone who took a more unlikely path to building something of such lasting value to the area.

In 1967 Abraham Fischler arrived at what was then called the Nova University of Advanced Technology. It was 300 acres of almost empty fields. He had a doctorate from Columbia and professorships at Harvard and the University of California at Berkley. He was attracted to a concept of a school exploring new ways of teaching science. But the school had blown through the money generously supplied by local families. At one time it had 17 professors and only four students. It still had dedicated supporters, including Hamilton Forman, whose family donated the land in Davie, James Farquhar, William Horvitz, Mary McCahill, Louis Parker, Abe Mailman, Edwin F. Rosenthal and Theresa Castro. But the average South Florida resident barely knew it existed. Some people mixed it up with Nova High School.

The founding president was a charming man, and great fun at a party, but he did not view part of his job as raising money he was freely spending. Nova had been launched with the support of both Fort Lauderdale and Hollywood leading families—two groups that previously had not often worked together. It had launched some promising programs—cancer research and oceanography among them— but it had very few paying customers. When its first students graduated in 1970, some thought it might be the last class. Dr. Fischler was asked to take over the Titanic that same year. He knew so little about business that he called on Hollywood’s Abe Mailman, to show him how to read a balance sheet. Money was so short he had to hold faculty checks. He had to innovate in ways he had never foreseen.

While cutting costs, he also cut a deal with New York Institute of Technology, whose wealthy founder, Dr. Alexander Schure, an education innovator himself, was able to fund the school. One of Fischler’s first moves was launching the law school and an off-campus program offering doctoral degrees for educators. Many, this writer included, considered that a cheap degree. Some of the school’s earliest supporters were turned off, both by the association with NYIT, a school they had never heard of, and by the off-campus programs, which they considered little more than correspondence courses. The idea, however, has since been imitated by major schools. And it saved NSU, which by 1973 was in the black. Cy Young, one of the school’s early trustees, summed up Dr. Fischler at the time:

“He’s a remarkable man. He’s a scholar, he’s a scientist, he’s an expert in education. And it turns out he’s also a damned fine administrator. And that’s very unusual, to find those qualities combined in one man.”

He displayed those versatile qualities until he retired in 1992, by which time the relationship with the New York school had ended, and NSU had 11,000 students and multiple campuses. The once empty field was now a busy and spectacular campus. He had attracted a second generation of benefactors. Their names are on the buildings and other facilities— Huizenga, Goodwin, DeSantis, Moran, Maltz, Case, Miniaci.

Dr. Abraham Fischler also has a building named for him. But his real monument is much larger. It is called Nova Southeastern University.

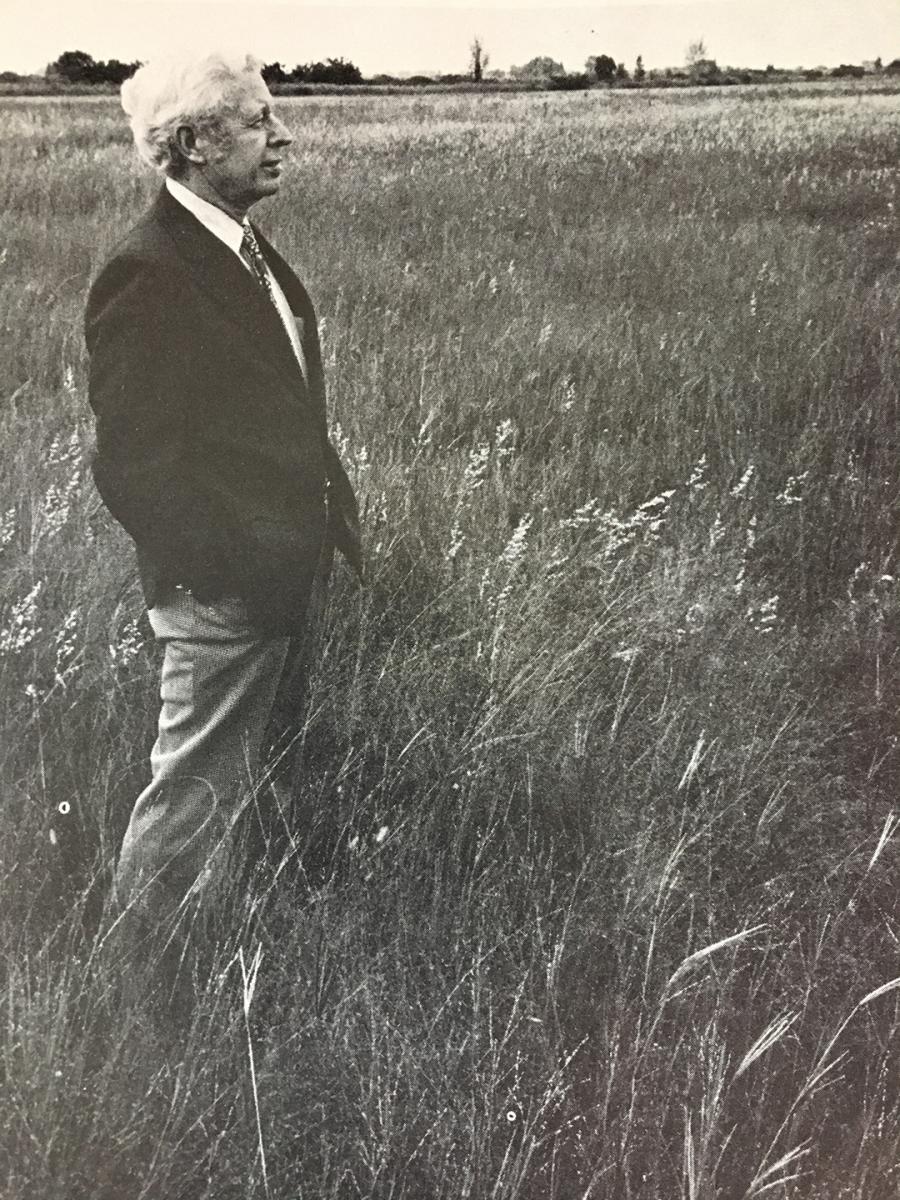

Peter Thornton, NSU's founding law school dean, posed on the future site of the school in 1983. Most of the now busy campus was still empty fields.

Photography by J. Schoonmaker