There are very few businesses that can claim to have been in Gold Coast magazine’s first issue 54 years ago. Maus & Hoffman is one of them. In fact, that high-fashion clothing store was on Las Olas Boulevard 25 years before Gold Coast was born. The firm is pushing 80 years in South Florida. William Maus and Frank Hoffman came down from the summer resort town of Petoskey, Michigan, in 1939. After finding locations in Miami too expensive, they opened on Las Olas a year later. Among Las Olas institutions, only the Riverside Hotel (1936) is older.

William Maus became a legendary pioneer on Las Olas. At one time a dozen stores from northern Michigan had followed his company to Las Olas or nearby cities. Las Olas was far less elegant than today’s venue. Among the neighbors was a gas station and auto dealership. Maus was the man who backed the boulevard’s first good restaurant, the recently closed Le Café de Paris. Today Fort Lauderdale’s center of nightlife has numerous fine restaurants, serving the massive influx of new downtown high-rise offices and apartments. Maus & Hoffman expanded around the state years ago. Today, it has locations on Worth Avenue in Palm Beach and stores in Naples and Vero Beach.

William Maus died in 1980, but all five of his children became active in the business. The family jokes that “Maus” means mouse in German; thus “a mouse in every house.” Bill Jr. still works in Fort Lauderdale, as did his late brother Tom. Their brother John, president of the company, runs the Palm Beach store. A sister, Jane Hearne, was in Naples before retiring. Tom Maus Jr. now runs the Las Olas Boulevard store. There is even a fourth generation in the organization. Ted Maus, son of Bill Maus Jr.’s son Arthur, works in the catalog fulfillment division in downtown Fort Lauderdale.

Although it began as a high-end men’s store, it has enlarged its offerings to include women’s clothing. And, as of last month, Maus & Hoffman has a new and appropriate location—in a sense a marriage with the Riverside Hotel. Its old location just a half block away was sold, and the new store has the advantage of an entrance on Las Olas next to the high-traffic Riverside, plus a second entrance in the back from the hotel’s lobby.

It is a union made in history heaven—Las Olas’ two oldest institutions. We wish Maus & Hoffman and the Riverside another 80 years of success.

Do you remember what you were doing the last time you turned 100? Nella McNally does. The Fort Lauderdale mother of three, grandmother of six and great-grandmother of nine, is being honored for her artwork both locally and by her Ivy League alma mater.

Ms. McNally’s full name is Ellen Carley McNally, but she goes by Nella, and that nickname goes back a long, long way. She celebrated her 100th birthday in August. The Galt Ocean Mile resident has been painting most of her life and works at it almost every day. That in itself is a story, but a better one is her unique connection to her old school—Yale.

She is a 1945 graduate of Yale’s School of Fine Arts, the oldest of its kind in the country. There she learned a form of painting that had been largely lost for hundreds of years. Egg tempera uses egg yolk as its base and was a common technique in Europe before oil paints were adopted in the 15th century. It was characterized by fast drying and exceptional durability. Just ask Michelangelo. It lost favor over the years, although some prominent artists, including Andrew Wyeth, preserved the medium.

There was a professor at Yale who taught tempera painting to McNally. The teacher is long gone and Yale dropped the course from its curriculum. It had largely forgotten his contribution until McNally’s work was called to its attention. That was done by another Yale alum, retired Fort Lauderdale lawyer Laz Schneider. He is a friend of the artist’s son, Phil McNally, also retired from banking. Not surprisingly, many of Nella McNally’s relatives and acquaintances have added the word “retired” to their resumes. But she is far from retired.

The artist will be part of “Yale 50/150” marking 50 years of Yale University admitting women and 150 years of their granting women art degrees. The event will run from March until November. Yale’s art gallery obviously is a major part of the celebration, and McNally will serve as a link to its past. The school made a two-hour video of McNally’s painting technique. The gallery is also adding one of her works to its permanent collection as an example of the egg tempera technique.

The centenarian artist is not without recognition at home. She was grand prize winner two years ago at the Bonnet House annual juried competition, and recently received a special mention for her more recent work.

The painting chosen for the gallery is a story itself, going back to 1960. McNally was asked by her sister to do a painting of a nun who taught at a now closed small Catholic college in New Hampshire. She was known as Sister Mary Margaret. The relative planned to give the painting to the order to which the nun belonged. The order, however, refused it, terming it “vainglorious.” They must have been humble nuns indeed. Today, no one knows Sister Mary Margaret’s real name. The painting was damaged by water and then restored and was in the home of McNally’s daughter in Connecticut. Now Sister Mary Margaret at last will have a permanent place in one of the world’s great universities. So much for vainglory.

The latest intelligence about accidents involving the fast, new Brightline train between Palm Beach and Miami is that it may be unsafe to sit on the tracks as a train going 79 mph bears down on you.

This astute perception stems from a recent report in The Palm Beach Post of a news conference in which relatives of people killed at crossings claimed that the new high-speed train is unsafe. One of the families was that of a man who police say was actually sitting on the tracks. He was not in a car trying to beat the train, which is the case of some of the other incidents at rail crossings.

Suicide by train is not all that uncommon, unpleasant as it sounds. Even though it has almost no grade crossings, the Northeast Corridor has seen its share of such grisly deaths. Those tracks are fenced in, but victims access the tracks by way of the numerous commuter stations along the route. According to Ali Soule, spokesperson for Brightline, eight of its 10 fatalities over the last year are being investigated as suicides.

The relatives, of course, do not think their kin committed suicide. They call for more safety features to prevent such incidents on a railroad that for years had slow-moving freight trains that encouraged people to take chances at grade crossings, knowing the odds were not that bad. Now, they are. Among the suggestions are more signs, voice warnings, etc. Those ideas, however, collide with the wishes of residents near the tracks who want the loud horns of the train silenced.

While we are a fan of Brightline and consider it long overdue, we concede the families complaining have a point. A train going almost 80 miles an hour at grade level through a busy city with numerous street crossings is inherently dangerous. All it takes is a little absent mindedness to find yourself stopped in heavy traffic on or near the tracks as the gates go down.

Brightline hopes to eliminate the few genuine accidents with simple advice. “We ask people to pay attention,” Soule says. “We ask them to avoid stopping on the tracks or going around gates. You don’t have to beat the train. Just follow the law and don’t take chances.”

Sound advice, but no more likely to be heeded than asking people not to drive 60 miles an hour in a 25 mph zone, or routinely bust red lights, or text while driving. Fatal accidents from such conduct are daily occurrences that make railroad mishaps seem rare.

There is only one real solution to Brightline’s problem: rebuild the railroad. If that sounds ambitious, it is, but it would obviously be a long-term project. There is a fast way to start. Eliminate some grade crossings. This has already happened. There are several streets in downtown Fort Lauderdale that were closed off years ago. A recent one was done to make room for the station just north of Broward Boulevard. The same thing happened in Palm Beach.

Closing off major streets is impractical, although bridging some is feasible where there are no major buildings or businesses that would be seriously affected. But there are dozens or less used crossings in Broward and Palm Beach County, which could be closed without bringing on the end of the world. It might seem that way to some neighbors, who would bring up the usual arguments about delaying emergency vehicles, etc. Those would be countered by homeowners on both sides of the tracks who would find their neighborhoods more private and free from a lot of traffic, eventually enhancing property values.

There are sections of track that run a considerable distance with only a few crossings. One example is from State Road 84 through the Fort Lauderdale-Hollywood International Airport, as far as Griffin Road—a distance of more than two miles. There are similar sections, especially in the less populated areas. If some crossings were eliminated, and the track fenced in, speeds up to 100 mph could be safely attained on those unobstructed stretches. That could permit trains to slow down a bit in congested cities and still maintain fast schedules. It would require an exemption from the 79 mph maximum limit, but that has been done on sections of the Northeast corridor where unobstructed main lines make it safe not just for the high-speed Acela, but also some conventional commuter trains.

Postscript: The train hasn’t even reached there yet, but some of the strongest criticism of Brightline has come from the Treasure Coast. The complaints about safety have reinforced the fact that the train had not planned to stop between West Palm Beach and Orlando. Ali Soule advises that Brightline is addressing that problem, exploring sites for stations in Martin County (Stuart) and Indian River (Vero Beach). That should not only silence some objectors but also greatly add to the usefulness of the service.

Image via

Once upon a journalistic time—the 1970s—South Florida newspapers were among the most successful in the country. The Miami Herald, owned by the Knight Ridder company, had a statewide presence with several bureaus, and had influential readers in most major Florida cities.

In Broward County alone it had a staff of 70 based in an office on Sunrise Boulevard. Its Broward circulation was an impressive 75,000. This was despite the fact that it competed with a very strong Sun-Sentinel, which at the time was one of two dailies in the same organization. The Fort Lauderdale News was the larger evening paper; the Sun-Sentinel was morning. There was also the Sun-Tattler in Hollywood, which had a respectable 50,000 circulation. The Herald also had competition in Miami from the small but feisty Miami News (ceased in 1988), which had some of the top talent in the area, and (until 1971) the Miami Beach Sun.

In terms of its Latin American coverage The Herald enjoyed the kind of respect the Washington Post does today in the nation’s capital. Knight Ridder owned 31 other papers, including The Philadelphia Inquirer, which it turned from a disgraced paper under former owner Walter Annenberg into one of the best in the country. Although largely forgotten today, the company also published the small The News in Boca Raton, which it used as a training ground for its promising young reporters and editors.

R.H. Gore, a tough and highly competitive businessman who sold his company to the Chicago Tribune, had owned the Fort Lauderdale News and the Sun-Sentinel for years. The News was one of the most profitable evening papers. Gold Coast magazine detailed its clout:

“Figures for the first eight months of 1973 show the Fort Lauderdale News running first in total advertising lineage among all the evening papers in the country.” The only papers with more advertising were all morning sheets.

It later became a morning paper and the name Sun-Sentinel was adopted when the two papers merged in 1982. Serving a fast-growing market of Broward and south Palm Beach County, its Sunday circulation reached more than 300,000.

The Sun-Sentinel did not have the journalistic clout of The Herald, but it did a good job on the bread and butter news, such as local politics and high school sports coverage.

The Palm Beach Post was also a very successful product, although its growth was stunted by competition from the Sun-Sentinel, which moved aggressively to dominate the southern half of Palm Beach County, and papers on the Treasure Coast, which limited its growth to the north.

Those glory days are long gone. As Dan Christensen recently reported on his Florida Bulldog blog, all three papers continue to lose circulation. Although located in high growth markets, the papers are losing readers faster than the national average. Virtually all newspapers are suffering. The pain began in the 1990s and has gotten worse year by year, as the internet and expanded television news have made print publications relevant to far fewer people, and have virtually destroyed the profitable classified advertising sections.

The numbers are grim: Christensen reported the Herald’s daily circulation has dropped in the last decade from 164,000 to 53,000, although its Spanish language Nuevo Herald adds another 25,000. The Palm Beach Post just a few years ago reported a daily circulation of over 100,000; it is now around 53,000. The Sun-Sentinel is down from 100,000 to around 75,000.

Like papers all over the country, South Florida’s dailies have gone digital, which although increasing readership, provides nothing like the print editions’ income.

Shortly after Florida Bulldog’s report, Buddy Nevins, commenting on Christensen’s work, reported on his popular Broward Beat blog that the Herald and Sun-Sentinel were considering a merger, which would likely result in staff reductions (which have already been drastic) as well as lack of competition.

Christensen and Nevins, by the way, are friends. They both have strong newspaper backgrounds—Nevins at the Sun-Sentinel and Christensen at The Herald. Their work helps fill the void left by the newspaper's demise. Nevins continues the political commentary, which distinguished him at the Sun-Sentinel. Christensen’s investigative reports command a loyal audience, which has grown beyond South Florida. Notable has been his dogged pursuit of an apparent cover up of the 9/11 attacks—the possible involvement of members of the Saudi Arabian royal family who were living in Sarasota. They had been in touch with several of the hijackers, and left the country in a hurry, leaving cars and household furnishings behind, just before the attack. This suspicious information was never given to former Sen. Bob Graham, who headed the 9/11 investigating commission. He has worked closely with Christensen in the effort to pierce the secrecy surrounding that tragic morning.

Back on topic, Buddy Nevins’ rumors are usually pretty reliable, and if the two major papers do merge, the Miami Dade-Broward market, which in the early 1970s had six daily newspapers, will be down to only one. No wonder the term “low information” is being applied to so many of our paperless citizens.

When major political events, such as the one we are now enjoying, are taking place, most low information people don’t really understand what they are all about. That is, until Hollywood steps in and makes a movie about it.

That was the case with Watergate in 1972. People who never read a newspaper did not understand what the fuss was about and could not fathom how former President Richard Nixon had to resign over a burglary that he did not even attend.

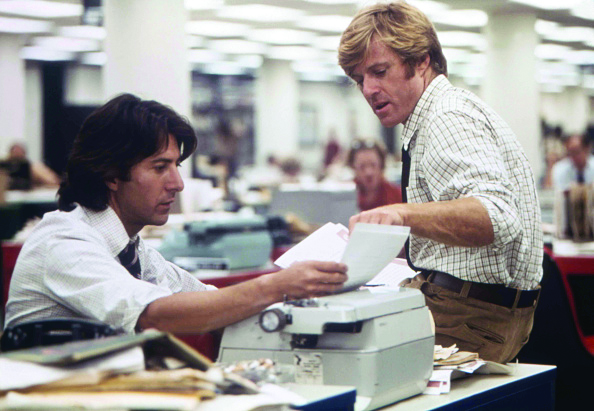

But then came “All the President’s Men,” and people realized it was about Robert Redford meeting in a dark garage with a very spooky fellow named “Deep Throat.” He went back to his desk at the Washington Post, and with Dustin Hoffman, tried to follow the money. And all this time they had Jason Robards breathing down their necks to make sure they didn’t get their paper sued to death.

The same thing happened more recently with the film “The Post,” which dealt with an event even older than Watergate, and has remained a fuzzy situation ever since it occurred in 1970. But now, thanks to Meryl Streep and Tom Hanks, we know it was about the publisher of the Washington Post worried to tears about her stock price, and not being invited to Washington cocktail parties—all because some unknown kid named Matthew Rhys had come up with Pentagon Papers that said the Vietnam War was a mistake, and Tom Hanks wanted to put it in the paper. Suddenly, after almost 50 years, it all made sense.

Many people don’t remember the real names of the people involved in these dramas, but they do recall who played them in the movie reincarnation. Robert Redford, Tom Hanks and Meryl Streep become more real than Bob Woodward, Ben Bradlee and Katharine Graham. And so it will be when the movie about 2018 turmoil is made.

To give Hollywood some help, we have begun casting the current episode, even as the first books are just appearing. It is, of course, tricky business, for we don’t know yet which of the dozens of figures whose faces are associated with current events will warrant a place in the movie when it all is put to bed. And we also have to find a role for some actors who are necessary to guarantee artistic success. Tina Fey, for instance, and Tom Hanks. Hanks should be easy to place, for he manages to look and sound like anybody he plays, and a number of figures in this film are reasonably close to his age and racial profile. Actors should bear some resemblance to people they play. Mickey Rooney would not be an ideal Shaquille O’Neal. Hanks could play most of the male roles in this drama. Michael Cohen and Paul Manafort, for starters.

Bob Woodward is a must, since his new book has gotten so much ink, and most people recognize him. Although somewhat older, Robert

Redford played him the last time around and, at age 82, he can still remember his lines if called on to repeat his interpretation of the 77-year-old Woodward.

Stormy Daniels, the pornographic film star who alleges a relationship with President Trump, could be played by any number of blondes. We might title it “All the President’s Women.” We think Daniels’ lawyer, Michael Avenatti, has star quality and should have at least a small role in any film. If he had not died 33 years ago, Yul Brynner was born to play him. Maybe Yul has a grandson.

Robert Mueller, of course, is a given. He’s the “Deep Throat” of this saga. Jason Robards, who played Ben Bradlee in “All the President’s Men,” would be just right in his prime, but his prime ended with his life in 2000. In a pinch, there’s always Tom Hanks. With “Saturday Night Live” doing hilarious impersonations of public figures, Kate McKinnon owns the Jeff Sessions part, as well as that of Hillary Clinton, if the former first lady gets a minor role. In truth, Ms. McKinnon could play the entire cast.

James Comey warrants major time, but presents a tall problem because of his height—he’s 6 feet, 8 inches tall. Back in the day, James Stewart (6 feet, 3 inches) would be a good choice, but alas he passed on in 1997. Looking over the lineup of tall actors currently alive, Liam Neeson (6 feet, 4 inches) stands out. Also 6-foot-3-inch Will Ferrell. He’s not too young for the 57-year-old Comey and he has a background in comedy, which could be an asset in this film.

Interestingly, in these kinds of productions a president does not need an actor. They tend to show up in actual film clips, or are viewed briefly from behind. Now, Melania is a different story. We need to get her in this flick, if only to justify the drawing power of Tina Fey. Unfortunately, her only part will be slapping her husband’s hand a couple times. No lines. Just like the original.

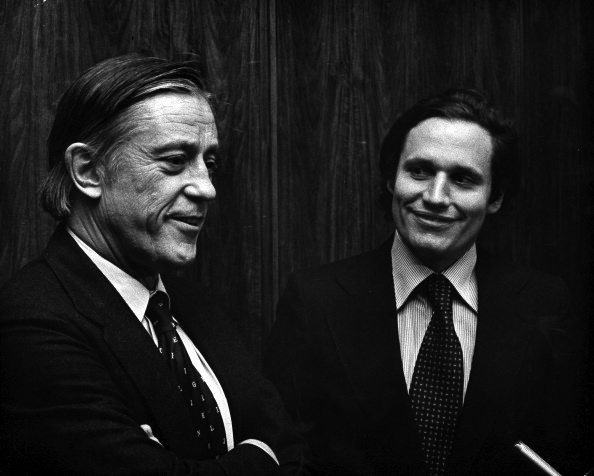

(Top) A young Bob Woodward with Washington Post editor Ben Bradlee during the Watergate era. Robert Redford improved his looks in the 1976 film, as did Dustin Hoffman for Carl Bernstein.

By Dominik Bindl | Getty Images

By Bettmann | Getty Images

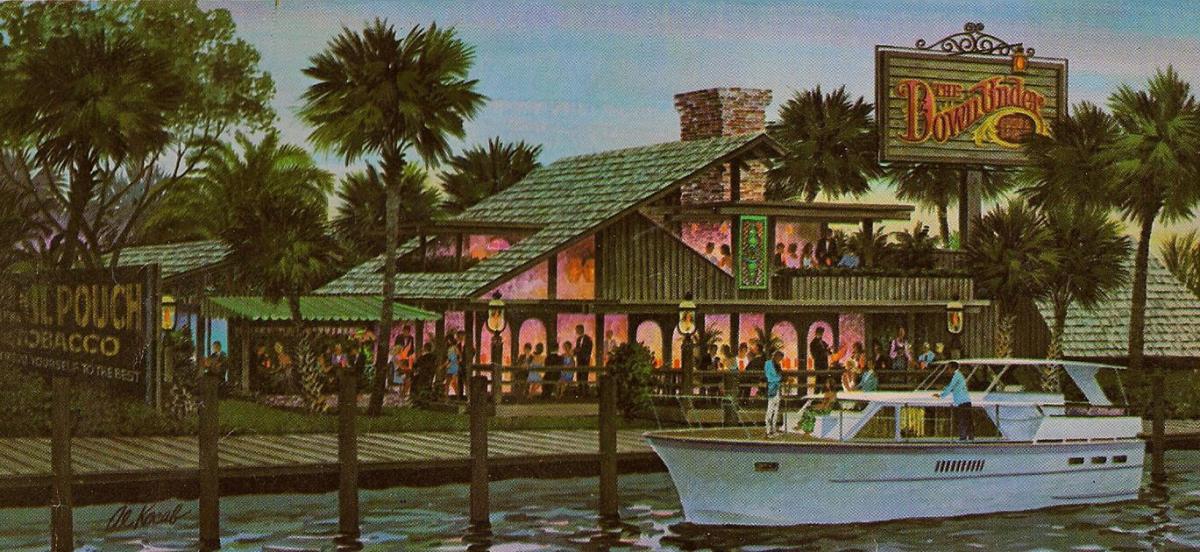

It appeared to be a perfect deal. Not only was the Down Under a successful restaurant, but it was an excellent investment for the handful of friends of Leonce Picot who backed him in what at the time was the most popular high-end restaurant in Fort Lauderdale. It also helped advance the careers of a number of people who were associated with it, including the young architect who designed it.

When Gold Coast magazine wrote about the Down Under in the 1970s, it wasn’t about the cuisine, which was excellent. It was about the deal, how well it had turned out for Picot, his investors and, ultimately, his loyal customers. What would seem to be a questionable location, almost hidden below the Intracoastal Waterway bridge at Oakland Park Boulevard, turned out, with the help of the name, to be an asset. It made Picot, who died at 86 on Aug. 24, seem to be a business genius.

Although the Down Under was the first of several successful restaurants (La Vieille Maison in Boca Raton and Casa Vecchia in Fort Lauderdale) owned by Picot, he was not a novice when he conceived his first venture in the late 1960s. He had grown up in Fort Lauderdale and had good business contacts, partly through his association with the Mai-Kai, which at the time was a hangout for a number of prominent business people. He was director of marketing for the restaurant, which had been successful since it opened in 1955. Picot had a good sense of what would make a winning formula.

His location was not his first choice. According to Dan Duckham, a young architect who was designing his first restaurant, Picot hoped to have a Las Olas Boulevard location. That was a logical choice, for in the ’60s there were not many restaurants on what today has become the leading entertainment venue in the area. But Oakland Park Boulevard was not a bad second option. Much of the town’s business was centered on Oakland Park and Commercial boulevards. Commercial was a particularly strong party drag. The late Jack Riker, a popular bartender known as “Turtle,” used to joke that he was working on a book called “How to see Commercial Boulevard on $1,000 a Day.”

Stan’s Lounge had shown that a waterfront location next to the Commercial Boulevard bridge was viable for a restaurant, but it still took a deft touch to make the Down Under the fast success that it was. Duckham created a beautiful design and Picot assembled a group of prominent backers. Part of the deal was free or discounted meals. His investors were there often, bringing friends. Then, as now, people attract people. As in the immortal words of Yogi Berra, “Nobody goes there anymore, it’s too crowded.”

Within a few years most of the investors had been bought out at a substantial profit, a pleasant bonus to the fact that they had eaten well and often and generally had fun. Dan Duckham, who went on to design almost 80 restaurants, was one of them. He had converted part of his fee into stock. Duckham, now in his mid-80s and still working in Cashiers, North Carolina, recalls: “I quadrupled my money, and we got a $3,000 dividend each quarter—$12,000 a year. The restaurant was going great.”

Indeed it was, and it continued that way for years, lasting under Picot’s ownership from 1968 until 1996. The Sun-Sentinel’s Mike Mayo, who wrote Picot’s obituary a few weeks ago, caught the flavor of the restaurant at its peak. He quoted Picot’s daughter, Laura Picot Sayles, describing busy Fridays when regulars arrived for lunch and were often still at the bar as the dinner hour approached. That may be an understatement. It wasn’t just Fridays. Some weeks it was that busy almost every afternoon. With time it earned the award of an abbreviation—regulars called it the DU. It also inspired some levity. There was a joke about a new cemetery in Plantation to be called the Down Under West.

Smart as he was, not everything Leonce Picot did was brilliant business. A longtime friend was as good a customer as any restaurant could have. His office was close to the restaurant and he was one of those who often went to lunch and was still around at the dinner hour. I don’t know how much he spent a week, but there were days when he dropped $50 on me, for lunch and lubricants. These were 1970s dollars. He entertained customers there all the time. One night he had a spontaneous office party for an employee who was getting married in a few days. He sent a staffer to the bar to get a bottle of Champagne from the bartender. Now, that is technically illegal; a restaurant isn’t supposed to sell stuff for takeout, but it happens all the time, especially for such a steady patron.

Leonce wasn’t working that night, and the manager on duty saw the person leaving with a bottle. There was a confrontation. We don’t know what was said, and in those days nobody had a cell phone to record the incident. But the Champagne did not leave the restaurant, and when our friend arrived at his office the next morning, there was a message to call Mr. Picot before he came in the restaurant again. The conversation was apparently not pleasant, and our friend did not set foot in the place for about eight years. The man eventually did attend a function at the Down Under. When Picot saw him, he could not have been more cordial, the Champagne altercation all but forgotten. All’s well that ends well—to coin a phrase.

Image via

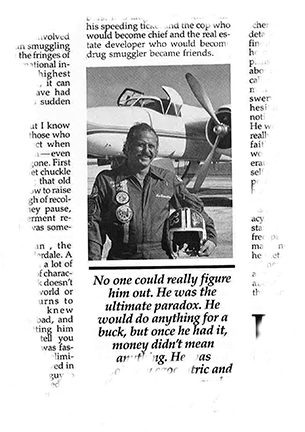

It has been 42 years since the World War II vintage P-51 fighter plane crashed in flames in the Mojave Desert of California. And almost that long since Gold Coast magazine assured the world that Ken Burnstine was really dead. He still is, 36 years later. And yet his legend lives on. Gaeton Fonzi’s book-length report, which appeared in three issues early in 1982, has proved to be the most enduring story in Gold Coast’s 53-year history. For more than a decade we have been getting requests for copies of that story. They usually come from someone with a personal interest in Ken Burnstine, an Ivy League educated, former Marine Corps officer, and prominent-developer-turned-big-time-drug-smuggler. How big? Burnstine died under mysterious circumstances while practicing for an air race, shortly before he was to testify against more than 70 associates in a massive drug running operation.

One of the requests a few years back came from a relative of a pilot who died in the crash of one of Burnstine’s planes. The man hoped the story might somehow show that his uncle was an innocent party, unaware that the plane he flew was a smuggling machine. Alas, he must have been disappointed. Burnstine’s pilots had to know what they were doing, loading up with drugs in the islands and Central America and flying at night on carefully planned routes to avoid radar and find secret landing spots around Florida. It was dangerous and illegal work, but they were well paid for it. And so were Burnstine’s investors, who doubled their money in a matter of days.

The most recent request, just this month, came from a man who said he was related to Burnstine. He is active military, suggesting he probably is too young to have known Burnstine. But he had heard about the articles and wanted to read them. Unfortunately, copies of those 1982 issues are few, but we had copied the pages for just such requests.

Burnstine was as colorful as the wildly painted P-51 he owned. That plane was his recreation. He had an enormous ego and loved attention, even bad publicity. He was often in the news for such things as keeping a lion in his home. Many people knew he was smuggling drugs for years before he got caught. Planes he owned were crashing filled with dope. People wondered how he got away with it. But at the time of his death he had been convicted and had turned government informant. His testimony at an upcoming trial could have sent dozens of South Florida people, some of them well known, to jail.

Fonzi’s story ended a myth that was even reported by the papers, that Burnstine had faked his death, that only a thumb was found in the plane’s wreckage, and that he was living the good life in Europe. Even today there are people who, if they remember Burnstine at all, suspect he evaded prison and is growing old somewhere with a missing hand. But Fonzi’s story quoted the coroner to the effect that more than just his thumb was found. His skull and teeth and the rest of his dismembered and charred body were also identified. Thus the title: “Ken Burnstine is

Still Dead.”

More dramatically, Fonzi revealed that there was a suspicion that his plane had been sabotaged with a motion activated bomb, which exploded when he showed off by rolling his plane at low altitude. Death prevented him from testifying against the many associates who backed his smuggling enterprise.

Moreover, Fonzi turned up information that even Burnstine’s closest friends did not know. He revealed that in the Marine Corps Burnstine was not a flier; he was a intelligence officer. Furthermore, for years he had some sinister CIA contacts. Fonzi, one of the best investigative reporters of his time, knew a lot about the CIA. He worked for five years for two government committees that had reopened the investigation of President John F. Kennedy’s death. He had connections beyond the scope of that work, which served him well when researching Burnstine’s murky past.

He learned that one man he was scheduled to testify against in the drug case was a supplier of arms to anti-communist Latin American groups. Fonzi wondered if one reason Burnstine avoided prosecution for so long was that he enjoyed protection by serving the government in some clandestine capacity. He interviewed Burnstine’s principal intelligence connection, who told him they had been good buddies, but had a falling out. It is obvious why. Burnstine could send him to jail. The connection also happened to be a specialist in sophisticated weapons, including devices designed to kill silently. Was one of those devices used to destroy an airplane and the notorious figure flying it?

We likely will never know. What we do know is that after 42 years, Ken Burnstine is still dead. And some people still care about his story. He would be thrilled.

We were going north on the Auto Train last year. We chanced to sit at dinner with a middle-aged couple, and we chatted about Auto Train. I told them it was the only long-distance Amtrak train that made money. The man across from us said, “No, it doesn’t.” I told him, with my usual authority, that over many years the Auto Train either made money or broke even.

“This trip is losing $21,000,” he said. A bit annoyed at being challenged on a topic that I am the world’s leading authority, I asked him how he knew that.

“I’m the accountant,” he said.

Well, that will shut you up in a hurry. Having done some research on the matter, it appears true that Auto Train is losing money, although in the past it did not. But there is also a question of how overhead costs are allocated. But any way you do the numbers, the losses don’t compare with the losses incurred by regular long-distance trains. Trains lose money on people; they make money on freight, including cars. Auto Train can make money. I should know. I was a stockholder when the service was launched as a private company in the 1970s. It made well over $1million one year, before it got in trouble with a second train serving the Midwest. More on that later.

Since that encounter with the accountant, we have taken another trip on Auto Train, just last month, which may have set a world record for using it. We first rode it in the early 1970s, and have been on it almost every year since. Usually we take it only one way, but several times we took it up and back over the Christmas holidays. We are not alone. Auto Train patronage has remained strong ever since the government took over from the original private company in the early 1980s. It tends to reflect the ups and downs of the general Amtrak ridership, but it has remained fairly constant over recent years.

Obviously, our family is a fan, so big a fan that I have long wondered why such a sensible idea has not caught on around the country. Having recently completed a two-week train trip halfway around the country, I wonder stronger than ever. It seems that most, if not all, of Amtrak’s long-distance routes could support some form of this service. The fact is that the original Auto-Train Corporation considered the combination of an auto train with regular service in the 1970s. It was planned for the ill-fated train to the Midwest.

It was a good idea but badly executed. The train began service between its present southern terminus in Sanford, Florida and Louisville, Kentucky. The locomotives were too heavy for the tracks it used, which were not up to the standard of the east coast railroads. Several derailments led to legal and insurance costs, which forced the company out of business in 1981. Amtrak took over at that point.

Still, given the number of tourists and snowbirds who visit Florida from Chicago and other major cities in the Midwest, the train could have eventually been a success had it been better planned and executed.

Considering the volume of traffic on roads paralleling other Amtrak routes, such as California’s Coast Starlight from San Diego to Seattle, one has to think that an auto train combined with the present Amtrak service would make sense, especially if some of the minor station stops eliminated. Those stops would slow the service, but train riders are not in a hurry. It need not be a daily service, at least not until traffic warrants. Auto Train users generally plan well in advance. Amtrak already has a train that runs three times a week—the Cardinal loops from New York to Chicago by way of Washington and Cincinnati. One has to think it would greatly improve Amtrak’s bottom line, and help keep the future of rail travel from perpetual uncertainty.

From a traveler’s view, the Auto Train makes sense. Our recent trip north cost $940 for the overnight ride. We go first class, with a bedroom for comfort and privacy. A coach seat is much cheaper. Our fare also included two meals on the train. We returned by car because we detour down the scenic Shenandoah Valley and stop to see friends in North Carolina. Had we pushed straight through with 10-hour drives, we would have had one night’s hotel expense.

We actually stopped for two nights, and with fuel costs and meals, our expenses were $650. But we also had our car for 10 days in the north. Had we rented one as big as our Toyota Highlander, our costs would have exceeded the train. This does not include the wear on the vehicle for 1,000 miles of driving. And those miles get more nerve-wracking every year as the interstates grow more crowded, and delays for accidents and road construction get worse.

And there is no comparison between sipping a glass of wine on a train, looking out at the poor souls crawling along in a heavy rain, contrasted with being two days out in those elements and with reckless drivers weaving from lane to lane and blasting by you, even if you are doing 75 miles per hour.

We should note that from time to time Amtrak planners consider the auto train concept for other routes. They should stop considering and get this train moving. As this country becomes more crowded and its population more mobile, a national expansion is an idea whose time has come. In fact, it came almost 50 years ago.

Image via

In essays describing our recent trip around the country by train, there was one element that is standard in such reports that we deliberately avoided—namely, our fellow passengers. We met some interesting ones, but detailing those interactions got in the way of describing some spectacular scenery.

First of all, it is very easy and at the same time not so easy to get to know people on a train. Many people just sit in their compact compartments or seats and read, look out the window or doze for much of their trip. The exception is the dining car for sleeping car passengers, where people are seated as they arrive. Attendants tell you exactly where to sit, and the next people to arrive are your companions for a meal.

People usually introduce themselves by first name only and exchange a few words on their backgrounds. You sometimes hear people hate to fly, but just as often they enjoy the change of pace a train offers. Invariably, they are not in a hurry, which means many are older and retired, or traveling, as we were, with younger family members. They were just along for the ride.

But the purpose of dining is to eat, oddly enough, which takes up most of these brief encounters—and they are brief. There are two or three sittings for lunch and dinner, depending on how crowded the train is, and the Amtrak staff, with great tact, manages to keep people moving. You don’t get life histories in these 30-minute interactions. One also tends to eat with some care. Trains rock even on the smoothest track, and it is not a good idea to spill coffee on a person you just met.

The lounge car is a different story. People who go there are motivated by the urge to enjoy refreshments and take in the views. Most Amtrak long-distance trains are bi-level. The lounge car has a downstairs bar with a few seats and an upper level, which is the one place where you can see easily out both sides of the train. It’s also an easy place to move around a bit and strike up a conversation with the person sitting near you. That we did whenever we could.

Our first encounter was on the ride from Los Angeles to San Francisco. We met an older woman who was en route from Southern California to visit family. She actually lives in Massachusetts in a pleasant college town. She was clearly high bred, from an elite eastern womens college. She had practiced family law in California before moving back east. She had been married 60 years, but her husband was not inclined to take a long train ride. He said, “You go alone,” so she did.

On the same trip, we spoke to a chap traveling alone from San Diego to Seattle. He appeared to be a very fit 50-something man. He was going north to take a trail hike. It must be a wild trail to travel that far. He hikes a lot. He has done the famous Appalachian Trail. He usually doesn’t do more than 20 miles a day. Originally from the Pittsburgh area, he had gone to California for college and never went back. By training a civil engineer, he switched careers to real estate investing and redevelopment. He does a lot of work on the east coast, especially in Savannah. He knew Fort Lauderdale well and mentioned Las Olas Boulevard.

He talked about the problems of rehabbing buildings in historic districts, all the requirements you had to meet to satisfy local preservationists. He seemed to have an amazing knowledge of things along the route until it was revealed he had a program on his cell phone that told him exactly what was going on each mile of the way. He even knew the name of a working oil field we passed. Did you know they had oil fields in northern California?

After a few days in the San Francisco area, we re-boarded the Coast Starlight for Seattle, where in the lounge car, as usual, we noticed a middle-age chap wearing a USMC cap with a number of campaign ribbons. It was an invitation to conversation. Sure as Quantico is in Virginia, he was a 22-year-old veteran of the Corps. He was returning from a visit to family in Southern California. He is from Oregon and was drafted after high school. He tested well, and the Marines wanted him. It was a good life. He served in Vietnam in 1968 but did not see much action. Pencil pusher. Remember “M*A*S*H?” He was Corporal Walter “Radar” O’Reilly and did paperwork for 3,000 men. Later stationed in Washington, D.C., he had a desk in the basement of the Capitol with a typewriter and was there 28 months. He never knew what he was supposed to do. He got the mail every day. Still doesn’t know what he was supposed to do. He married high school sweetheart. She died of cancer. He became quickly bored in retirement and went to school to become a bus driver. He now drives a regular route to Idaho. It’s a four-day gig. It breaks down once in a while. It’s a good life.

Same trip. Talked to a bald-headed man who could have been in the “Coneheads” cast. He was traveling after visiting his family. He now lives in Virginia near D.C. where he is a financial analyst. He wasn’t terribly talkative. He was looking forward to turning 72 and getting social security. As a financial guy, we trust he will spend it wisely.

After another two-day layover in Seattle, we got to the part of our trip we most anticipated. The Empire Builder is Amtrak’s busiest long-distance train. On the second day out we noticed a young fellow chatting with another passenger. When the passenger left, we struck up a conversation. He was from China and in the U.S. for school, but with his Asian accent we could not figure out exactly what school he was attending. He did seem to be a traveler. He had been on trains around the country and seemed to know the east coast pretty well. We got the impression he was trying to learn everything he could about the U.S. and enjoyed talking to strangers on a train. He seemed bent on improving his English. We told him he had just met America’s greatest authority on almost everything. He realized a joke when he heard one, even if he didn’t seem to get it. We wished him well. China could use a few good men.

We also chatted a bit on all three trains with our sleeping quarters attendants. In all cases, they were cheerful and attentive, a good quality for an attendant to have.

Conversations we did not anticipate were with Uber drivers. Our son, who was in charge of logistics for the entire excursion, is an Uber junkie, and we took the opportunity to pick the drivers’ brains as they hustled us from hotels to trains and around the sights of several cities. Our first driver in Los Angeles was a high-spirited lady who could not have been nicer. When we told her we were touring the country by train she offered to park her car and join us on the spot.

Of the dozen or so drivers we met, only one or two spoke little English, but the rest were impressive people—tour guides as well as drivers. They all had immaculate vehicles of recent vintage, and they drove carefully and well. Only one of them seemed to be working full-time as a driver. He had worked for Boeing in Seattle. He seemed to be a college dropout still finding his way in a young life. Another was a retired teacher with a platinum Einstein hairdo who entertained us as he drove. He was a Michigan grad and big fan of Wolverine football. When we mentioned our son went to Notre Dame, he offered to let us out of the car right there and then.

One of the drivers in the Seattle area was a slender woman about 40 who did not say much until we asked questions. She was Canadian born but had lived in the U.S. for some time. She seemed overqualified to be driving for Uber. Turns out her real job is a life coach, one of those people, as you may know, who coach people about life. We asked where she lived before Seattle, and she said, “Schuylkill Haven, Pennsylvania.” We told her we knew it well, just down the road from Pottsville. We asked her if she was familiar with Swedish Haven. She hesitated, and then said, “No.” We told her that was the name John O’Hara used for Schuylkill Haven in his numerous novels and short stories set in the Pennsylvania coal regions. We sensed she had no idea who John O’Hara was, or that he was once a best-selling author, and is still considered one of the great short story writers of his day. What the hell, his day ended in 1970. Sic transit gloria mundi.

Still, few people up that way do not know the name John O’Hara. In his lifetime he was despised for his portrait of the area whose hard drinking, sex-crazed characters often resembled real people. Today, he is a tourist attraction, literally. They have tours of the many places that appeared in his stories.

We met these interesting strangers on trains and still wonder what a life coach was doing in Schuylkill Haven. She obviously wasn’t a coal miner’s daughter.

Image via

In previous blogs, we have described our effort to travel around the country by Amtrak. We got as far as San Francisco before the complications of life delayed our reports. Several weeks later, rather late than never, which could serve as an Amtrak slogan, we continue our journey. First, we note the train from Los Angeles to San Fran was only mildly late. It was right on schedule until we lost about 20 minutes waiting for a freight train to clear the track only a few miles from Oakland's Jack London Square Station, the Amtrak stop serving the Bay Area.

After a most pleasant visit with relatives, we continued north toward Seattle on the same train that had brought us from Los Angeles. It was a bit late, which is on time by Amtrak standards. It leaves Oakland a bit late in the day, so much of the journey is made in darkness while those of us with bedroom accommodations are trying to rest. We can report, however, the sun also rises in Oregon, and the final hours of that leg were slow but spectacular. The brown hills of California—California PR people have always called them “golden”—had been replaced by dense, green mountain forests. Not so late we pulled into Seattle's King Street Station.

The weather was borderline miraculous and had been ever since we set out in New Orleans. The locals, who are used to damp and misty mornings, advised us to enjoy the blue skies while they lasted. That we did, especially on the ferry ride to Bainbridge Island, where we had rented an Airbnb on the water. It was a beautiful spot, just one of several scenic islands on Puget Sound. Here, the family—we had been joined by additional relatives in San Francisco—hosted a little party. The guests were Brian and Kavita White. Both formerly worked for the Sun-Sentinel. He was sports editor and now is sports editor for MSNBC in Seattle.

After enjoying Seattle's ridiculously busy tourist district for a day or two, we were back at the King Street Station, ready to board one of the jewels of the Amtrak system—The Empire Builder to Chicago. The train did not make a good first impression. It is the beginning of the line, so there were no freight trains to blame, but it was an hour late just showing up at the station. But if you have to wait at a station, King Street is the place to do it. Built in 1906, it opened in an era when railroads were the modern mode of travel, and rail companies took pride in the architectural distinction of their big city terminals.

Some cities have let these old stations be destroyed. New York's Penn Station is a prime example. Its tracks remain underground, but the old station was razed to make room for Madison Square Garden. Seattle, however, preserved its elegant station and modernized its passenger platforms with a glass walkway over the tracks, leading to CenturyLink Field, home of the Seahawks, and nearby Safeco Field, the Mariners ball park. It also serves a busy high-end commercial district nearby.

Once underway, the Empire Builder lived up to the billing. It begins with a late afternoon ride along the edges of Puget Sound. As with the Coast Starlight along the Pacific, there is nothing between the tracks and the water as the train weaves its way into the hill country of eastern Washington. Night closes the view, and when daylight returns the train has crossed the northern sliver of Idaho and is entering Montana's Glacier National Park. Amtrak times its schedules to provide daylight views of its best scenery, so even when a train is late, as we were, there is still prime time visibility. This majestic section of the northern Rocky Mountains was preserved by the railroad when it came through in the 1890s. The management of the Great Northern Railroad—now merged into BNSF—lobbied for the park's creation in 1910, sensing it was creating its own tourist attraction. And that it has. The lounge car, with its visibility on all sides, is jammed for the ride through the vast splendor of the park.

The train was now seriously behind schedule, and the situation did not improve as it exited the mountains and entered the rolling brown hills of North Dakota, sections of which resemble a basket of biscuits. Soon the Great Plains were reached, and another nightfall breaks the monotony of endless flat vistas broken only by grain elevators gleaming silver in the late day sun.

Morning brings much of the same, but by now most of North Dakota has been crossed, and the plains are now rolling into Minnesota. The railroad, which had been skirting the Canadian border for hundreds of miles, begins angling to the southeast, bent on reaching the twin cities of Minneapolis and St. Paul. Alas, it was now reaching them some five hours behind schedule.

There is a reason this train runs so late. In recent years there have been natural resources discovered along the route, greatly increasing the volume of freight traffic on a line that still has miles of single track. That means trains pull off on occasional sidings to let traffic pass in the opposite direction. The train that stops is usually Amtrak. Railroads vary in their treatment of Amtrak. Some take pride in keeping the passenger trains on schedule; others treat hosting Amtrak trains as something of a corporal work of mercy. They almost always give priority to their moneymaking freights. It does get tedious when you sit for 15 minutes, looking out a window at land that does not have so much as a grain elevator for scenery. That's if you are lucky. As often the view is blocked by what seems like a 20-mile long freight rolling by at 10 miles per hour. BNSF (that’s Warren Buffett’s railroad) has been double tracking to relieve congestion, but that is a slow job. It is working with the state of Idaho to remove a major bottleneck. A 1.6-mile bridge built in 1905 has only a single track, and the railroad wants to build another bridge. That’s a serious project, but it's one that needs to be done to speed up traffic. The delays were not unexpected. We had checked out the on-time performance of the three trains we rode, and the Empire Builder was known for delays.

Still, after being on a train for more than two days, the lateness becomes irritating, but it was worse for passengers who planned to meet other trains in Chicago. There apparently were more than a few in that category, and there were announcements of arrangements being made to accommodate them if they missed their connections. Some were advised to detrain before we reached Chicago. I don’t recall the reason for that; it did not affect our family group, and we were staying overnight before flying home.

It did take away from the fact that the train seemed to make up some time as it entered the fast corridor from the Twin Cities through Milwaukee and into Chicago. We recalled that back in 1930, a steam locomotive racing from Milwaukee to Chicago set a speed record of 104 miles per hour. Today Amtrak has a speed limit of 79 miles per hour, the exception being the Northeast Corridor, which is owned by Amtrak and allows speeds over 150 miles per hour. We should note that people who ride long distance trains are generally not in a great hurry. Since the Wright brothers, there have been faster ways to cross the country.

The purpose of our trip was the trip, and my son Mark and his family joined on various legs. The journey, which included two layovers, took just about two weeks. For the grandkids, who have been to Italy and Ireland, it was a chance to see their own country from the same level as those hardy souls who first crossed it some 200 years ago. Home for a few days, we asked Mark to reflect on the journey.

“There are a lot of farms in the United States,” he said.

Image via