Thanks to Governor Ron DeSantis’ loyalty to President Trump, Florida has gotten some really bad ink on its handling of the Coronavirus pandemic. Shots of busy beaches continue to appear in the national media. Those presenting those images don’t bother to note that Florida is a very long state, and the reckless-seeming venues featured are not in South Florida, which has been shut down for weeks.

The fact that county officials in Dade, Broward and Palm Beach all acted promptly when the scope of the danger became apparent may have been part of the reason DeSantis waited so long to act for the whole state. He may have figured the hottest spots for the disease were already in quarantine, and because much of the state did not seem to have a problem, why take drastic measures? That seems to be President Trump’s attitude toward the country in general, although it has become clear that is faulty reasoning which could cost thousands of lives.

As for our back yard, we are about to see if prompt action works. Florida is predicted to have its peak of the virus in the next few weeks. It will be interesting – if saving thousands of lives can be described as interesting - to see if South Florida’s precautions have paid off. Certainly, the drastic curtailment of business, especially the many enterprises geared to tourism and retirees, deserves a reward.

Among the more notable, and economically painful, shutdowns were the Fort Lauderdale beach and all its bars where spring breakers packed in. An ideal atmosphere to spread the virus. Although young people often show only mild or no symptoms, the evidence is that many of them are infected with the virus. The fear has been that they can carry the illness home to parents, and grandparents. Many, if not most of the latter have underlying health issues that set them up for the kill.

Seniors are among the many wondering if the precautions forced on South Florida residents will make a difference. It would certainly seem that ending spring break should bear fruit. Most of the visiting kids left town a few weeks ago. If infected they are spreading it in their home towns by now, although it would seem their contagiousness is less of an issue every day. People vary, but most of the youngsters should be close to passing the highly contagious point. As for local youth, if they are anything like our family, they are carefully segregated from seniors – or vice versa. It is hard to believe that these measures won’t lessen the chances of explosive contagion as seen in New York or other densely populated centers where people can’t avoid each other even if they try.

As President Trump is so fond of saying, we’ll see what happens. Now that's going out on a limb

The latest controversial assault on history does not involve renaming Hollywood streets named after Confederate generals. It’s worse. Now Dixie Highway, the oldest road connecting the world to South Florida, is under attack in several cities, where some people find the word Dixie offensive because it recalls the Civil War, specifically the southern side and the days of slavery.

Those who object to such name changes usually cite the inconvenience and confusion of changing their addresses, and sometimes even driver’s licenses. On the Hollywood street matter, we suggested that instead of changing the name of the streets, we should just change the people they were named after. Lee Street after Spike Lee, Forrest Street after Forrest Gump, etc.

Our objection against eliminating Dixie Highway is fundamental– it propagates a misunderstanding of that war and the events before and after it.

It relates to a distinction being lost to history between the cause of that terrible war and the reason men fought it. The cause of the war was slavery. Even the distinguished leaders of the south, such as Generals Robert E. Lee and James Longstreet, recognized that obvious fact. Longstreet, a Georgian, was unpopular after the war because He supported his friend, Union General Ulysses Grant, and argued for the freedom of slaves, many of whom were only nominally free in the decades following the conflict.

However, the reason most men fought and so many died was not about slavery. That was the motive of southern political leaders, who then as now were heavily influenced by financial interests. The historian Shelby Foote, who spent 20 years writing a three-volume history of the war, noted that the average soldier on either side “didn’t give a damn about slavery.” The northern men fought to preserve the union; the southerners thought they were fighting the second war of independence.

That’s where states' rights come in. Southern political leadership used that as an excuse, and in a sense they were right. For the almost 90 years between the Declaration of Independence and the siege of Fort Sumpter, there was tension between the idea of a union and the rights of each state to be its own boss. In many cases, men considered their highest loyalty to their state. Robert E. Lee, whose Virginia was among the last states to secede, was conflicted. But he said he could not fight against his own state. Many in Virginia refused to secede. West Virginia was born when its citizens insisted on remaining in the Union. They seceded from Virginia.

Those opposed today to southern memorial symbols portray the southerners as traitors. It was just the opposite at the time. The few prominent generals, such as the Union’s George Thomas (a Virginian) or Confederate John Pemberton, a Philadelphian who married and served much of his time in the south, were considered traitors on their home turf.

That sense of state sovereignty was manifested during the war by the rebel states. Governors of some Confederate states were reluctant to cooperate with their co-rebels. They were jealous when officers from their state were bypassed for high ranking positions. And some actually hurt the Confederate cause. Example: Although exact numbers are in dispute, the governor of North Carolina has been accused of hoarding for his own state’s troops, enough uniforms (the number has been reported as high as 90,000) to outfit the entire Confederate army late in the war.

Few appreciated the dilemma facing southern leaders and ordinary soldiers more than Abraham Lincoln. In his two greatest speeches, the short one at Gettysburg, and his second inaugural shortly before his assassination, his words were inclusive. When he praised “the brave men, living and dead, who struggled here” at Gettysburg, he was careful not to emphasize men of either army. And his “malice toward none, charity for all” words were an obvious olive branch to southerners. When he closed that speech with “let us care for him who shall have borne the battle, and for his orphan and his widow” he did not choose to identify victims on either side.

So where does this nonsense end. Is the word “Dixie” to be expunged from our language? Will we rename Dixieland music? And Dixie cups? Are Winn Dixie stores in danger? And should we reconsider the name Southern Boulevard in Palm Beach County? What would Abraham Lincoln say today? Well, we have a strong hint. Even though he knew the tune had become the anthem of the south, he said “Dixie” was one of his favorite tunes, and he even had it played at state occasions.

And that ain’t just whistling “Dixie.”

There has been quite a stink about the sewer leaks fouling streets and waterways in Fort Lauderdale. Nobody knows quite whom to blame. That regarding the past, not so much the future. The overbuilding that is going to make the problem worse in future years, if not months, was approved by planners and city commissions going back a decade.

Of all the proposed fixes for the problem, the cure for overbuilding is easiest to implement. You can’t stop the buildings already up or well along the way, although the idea of a moratorium has great appeal to those already living here. Our solution is much easier. Let the buildings go up, just don’t connect them to water. The truth is, this would likely slow sales, but if we're already being honest, the harsher truth is that some of the new buildings may be subjected to isolation by flooding.

Those who do rent or buy in the new high rises would need to use bottled water, but because the buildings would not need plumbing, that is not too great an expense. The bigger problem is disposing of human waste, but that issue has considerable historical precedent. It was only a few centuries ago that toilets did not exist in any capacity, although the concept goes back much farther.

People in merry old England used holes in the ground, or for those lucky enough to live indoors, they had chamber pots. As recently as the 1950s, we personally were exposed to an outhouse while visiting poor relations in northern Pennsylvania. Disposing of the product in Florida requires ingenuity, but again, history is a teacher. In pre-toilet days, many people just emptied their chamber pots out the window.

If you notice, these tall buildings usually have balconies, often very small ones, and you rarely see anybody up there enjoying the view of the balconies on buildings across the street. Perhaps, in anticipation of the water crisis, the balconies were added so people could simply empty their chamber pots on the streets below. This would effectively contaminate sidewalks (and people on them), including windswept balconies on lower floors while avoiding the fuss and expense of installing pipes that will eventually break anyway. This may be one reason units on upper floors tend to be more expensive

People who wash their hands every 10 minutes may argue that our proposed waste disposal system is hardly an improvement to sewer pipes bursting and flooding streets. But after all, Rome wasn’t built in a day. And one of the things Romans did build was underground sewers that lasted for centuries and even rivaled modern-day systems.

The recent news that a developer wants to put a large complex on the extensive Searstown property at U.S. 1 and Sunrise Boulevard in Fort Lauderdale would be a welcome event. Twenty years ago. Today, it is appalling that anybody would think of adding more people to downtown Fort Lauderdale, with the sewage system exploding in our streets and thousands of new residential units already underway and yet to be occupied. The community is reacting accordingly, wondering how the infrastructure was allowed to decay at the same time such massive overbuilding was permitted. It would be good to see this prime property put to a use that would enhance the community, but given the circumstances any high-density development is unthinkable. No responsible, or honest, government officials can approve the present plan.

The situation was extensively reported on recently by Doreen Christensen in the Sun-Sentinel. She included an excellent history of the once-thriving Searstown, and in that connection gave us a call. She knew that we came to Fort Lauderdale when Sears was still going strong, and with a young family, it was likely our first stop for general household needs. This was before Walmart, Target, Home Depot, Lowe’s. Best Buy and a half dozen other chains, each competing for pieces of Sears’ business.

What Ms. Christensen did not know was that Sears played a major part in our family history going back 100 years. It is not an entirely happy story. It begins when Sears, then known as Sears and Roebuck, based in Chicago and going strong for two decades, needed an east coast facility. It chose Philadelphia. A massive nine-story building with a 14-story tower opened in the city’s northeast section in 1920. The building, which housed both manufacturing and its booming catalog business, looked like a state capitol and it quickly grew its employment to thousands of people. One of them was my mother, fresh out of high school. A few years later she met my father, who also worked there.

By the 1930s dad had a responsible job. He had become a plumbing and heating specialist and was working in Sears pre-fab housing unit, located at Port Newark, New Jersey. We never knew exactly what he did and attempts to contact Sears to find out in recent years have been futile. Records had been destroyed and the company had bigger things to worry about. Anyway, our guess is that dad helped plan the plumbing and heating for a variety of Sears houses, which ranged from modest cottages to large 10-room structures with expensive touches such as oak floors. Sears called them “kit homes” and big or small, the units arrived, usually by train, as a complete package with all plumbing and electrical fixtures. They were marketed through its catalog. The company was years ahead of its time, and over a 32-year span, Sears sold more than 70,000 homes. A handyman, often with help from neighbors, could build his own house. Many did in rural parts of the country. In some sections, those still standing have become tourist attractions.

In all ended in the late 1930s. Records today are hard to come by, but apparently the housing unit was not making money. The country was emerging from the depression, but the housing market was still soft. Sears decided to exit the business. In 1939 dad managed to be transferred to Elmira, New York, where he managed the plumbing and heating department of the Sears store. Elmira in those days was a pleasant little town, and we had a good life there. Mother had me taking riding lessons at age four, but that ended when a horse, not knowing a little person was on his back, nearly rolled over on me. But after a few years, our mother was homesick for her family in Philadelphia. At her urging, dad managed a transfer back to the big Sears facility in Philly. It was early 1942, and World War Two was changing everything. Dad no sooner arrived back in Philadelphia than he got fired. It seems Sears figured the war would hurt business and was cutting back. It turned out to be a bad calculation, for its young men were leaving for the service. Anyway, a man dad had worked with years before was tasked with the job of cutting middle-management jobs.

“I never liked the guy,” dad recalled, “and I never bothered to conceal it. He got me back.”

At 46, with three young kids, dad was on the street. He took a menial job for a year, collecting payments for an ice company. A lot of ordinary people still had ice boxes and did their wash by hand. He then got into the insurance business and stayed in it for 25 years. But we always thought he never got over leaving Sears and a company to whom he had given the best 21 years of his life. However, we continued to buy our stuff from Sears over the years.

Dad died shortly after our move to Florida but we still patronized Sears. We bought at least one refrigerator (iceboxes were history) and whatever tools we needed came from Sears fine Craftsman line. We also continued to buy Christmas gifts from its popular catalog. It made shopping for the kids easy. Sears offered a lot of toys. At one time it sold the famous Lionel Train sets, items built exclusively for its stores. Until one year – It was about 1973 – Peg got nervous when the stuff did not arrive the week of Christmas. She called Sears and was assured the toys were on the way. But when they did not arrive by late on Christmas Eve a certain panic set in. Aside from what had been ordered, there was almost nothing for the kids.

Smith Drugs on Sunrise Boulevard in the Gateway shopping center, owned by the late Shelby Smith, came to the rescue. It was open after dinner and in about an hour’s frantic time, we managed to buy a ton of stuff, not all toys, that kids would like. We got some things we never would have thought of. Some of it already came in Christmas packaging, so there was no late wrapping session. The kids never knew the difference.

But we sure did. We had lost confidence in Sears. It was the first sign that the great retail empire was going the way of all empires. How could any company that fired the best man I knew and damn near ruined a Christmas, possibly survive?

One of the side effects of a health epidemic is a decline in the stock market. As this is being written, the Dow Jones average has lost almost 1,000 points in the last few days. Experts blame it on the Coronavirus in China, or more precisely the fear that it could spread into a worldwide epidemic that could hurt businesses and lives. Some may wonder why there is all this fuss about the virus. We have all seen flu epidemics throughout history.

The reason for the concern is that medical people have memories. There is virtually no one alive who was old enough to experience a worldwide epidemic firsthand. And increasingly few of us even had relatives who remember 1918. We are among the few. The McCormick family of Philadelphia had 10 children when World War One was going on. A deadly flu epidemic had appeared in Europe. It was initially called the Spanish flu because early cases were found in Spain, but it is doubtful it began there. It’s more likely the disease started with soldiers in the miserable trenches of the war. Wherever it started, it spread quickly, and before it was over, 50 million people had died. Over 600,000 died in the U.S., more than the number of Americans killed in the war.

The disease reached the United States in three stages, and nothing so deadly had been seen in American history. One of the worst-hit cities in the U.S. was Philadelphia, where 12,000 died within a year. The McCormick family saw it tragically up close and personal.

The first wave of the disease hit in the spring of 1918. The disease was so deadly that it killed many people before they even realized how sick they were and could seek medical treatment. The medical community was overwhelmed. Doctors and nurses caught the disease from patients. Many died. The city took drastic measures to prevent the contagion, including closing bars and other gathering places.

The McCormick family’s first casualty was the second oldest, Timothy, who died on May 29, just short of his 25th birthday. In Philadelphia and elsewhere, the disease seemed to pause, but in the fall, the second and most deadly wave hit the country. The oldest in the McCormick family, 27-year-old William, died on October 19. When he became ill, his sister Mary, 24, left her nursing job in Brooklyn to take care of him. One morning she told the family that his fever was breaking and the crisis had passed. She left for Brooklyn. William died the next day. Mary herself came down with disease and died within two weeks. These three were the eldest of the McCormick clan. The fourth oldest, John, got the flu at age 22 but survived. You would not be reading this had he not. He was your writer’s father.

There were six younger children in the family. They lived in crowded circumstances, but none got sick. This was consistent with one of several mysteries surrounding the epidemic. It struck those in the prime of their lives, largely sparing the young and elderly. One theory to solve this mystery blames aspirin as the culprit. It had only been in common use for a few decades. We will never know if our family used it, but Philadelphia was a pharmaceutical center (still is), and it is likely many people took it to relieve fevers. Aspirin toxicity, which can be deadly, was unknown at the time. People may have figured if a couple of aspirin helped with colds and fevers, a bunch would work even better. Many of the dead had symptoms of aspirin toxicity.

Another mystery is why the flu epidemic ended as suddenly as it began. Why was the disease so ferocious in the first place, unmatched by anything in the last 100 years? And why it was so severe in Philadelphia?

But we seemed to have learned from that tragic experience. Today we know the dangers of overdosing with common pain killers. The drug industry has come up with antibiotics that are effective against disease epidemics. Unlike the 1918 flu, coronavirus is well known and a new strain of it was quickly identified. But when an outbreak of something so infectious occurs, the medical community takes no chances, always wary that diseases have a mind of their own and can have unpredictable and terrible consequences. Much more than a decline in the stock market.

A few months ago, President Trump was criticized for proposing the U.S. buy Greenland. Greenland has natural resources, including some P-38 airplanes buried in ice after they made forced landings during World War II. As Greenland melts, those planes can be salvaged for display in museums. Is that enough to warrant the purchase? Obviously not. But the president is not entirely off base. He just wants to buy the wrong place.

What he should consider buying is Central America, or at least one of the countries that is causing the President grief by letting people leave to escape miserable living conditions. Whereas Greenland is not for sale, we understand everything in Central America is, and buying something there would be a step in the right direction for President Trump to stop the invasion of those he wants desperately to wall off. By making part of Central America a state, we could wall people in. With the stroke of a pen, they would be living in the U.S., making the long and dangerous journey to our southern border unnecessary. It need not even be a state. Let the people decide. Maybe they would just want to be a territory with all the comforts that residents enjoy in Puerto Rico.

After more than an hour’s exhaustive research, Guatemala, or strategic parts of it, top the list of potential acquisitions. It is well-positioned just south of Mexico, and narrow enough to permit a mile-high wall to seal off those who are not positively contributing to our country.

It would also block the escape route for an untold number of gang members who are killing each other, and anybody who tries to control them. Those in Trump’s administration who love wars would be more than satisfied. The first step toward economic growth would be to build an enormous military base. Our military would take care of the gang problem.

Once pacified, the U.S. could build tourist attractions, luring those people who visit Florida but will need new destinations once we go underwater. Guatemala has some high ground that should be safe from climate change for most of the century. Lacking ice, it should not suffer Greenland’s meltdown. Children in cages on our southern border can go home, and others would be welcome in from nearby countries. President Trump could oversee the greatest building boom in the history of mankind, something even he would have difficulty exaggerating. There would be plenty of jobs for honest citizens. Guatemala would look like downtown Fort Lauderdale.

President Trump should seriously consider this problem-solving real estate venture. Just make sure Guatemala pays for it.

The relief effort for the massive Hurricane Dorian damage in the Bahamas involves every mode of transportation available. It takes one back in history to June of 1940, and a place called Dunkirk in France. There, German forces surrounded the remnants of a French army and most of the British Expeditionary Force. The only way out was by sea from a place that had no natural port.

The call for help was heeded by hundreds of British boat owners, non-military people who voluntarily crossed the rough English Channel in craft small enough to enter shallow waters. There, soldiers waded out to meet them, often protecting their rifles by raising them above their heads, and were escorted to larger ships. In a week’s time, more than 300,000 British and French soldiers were evacuated, saving a force of trained men that eventually was part of a winning coalition. Those citizen saviors did not ask for permission or need visas, or any other authority. They just got in their boats and did what had to be done.

Today, under vastly different circumstances, hundreds of small civilian boats and private aircraft have been crisscrossing the 100 miles of water delivering supplies and bringing back refugees who have lost everything but their lives. There are so many vehicles involved that in the chaos of the first few days, rescue planes were getting in each other’s way, creating confusion and even shutting down some airports because of minor accidents. It overwhelmed the organizations that run them. Add to that red tape and delays on both the islands and U.S. airports by officials who have never seen such challenges and insist on playing by the book, resulting in delays for flight plans approval, when Dunkirk speed and improvisation was needed.

A vivid description of the situation comes to us indirectly by way of our friend and local investment manager Nik Bjelajac. He, in turn, is forwarding reports sent to him by David Ehlers, an investment advisor (we wrote about him in the 1970s) who made his money in South Florida and now lives in Las Vegas. He has been receiving messages from his friend, a pilot named Peter Vazquez. This man is a boat captain, but he also is a veteran pilot and it was this skill that made him one of the first to join the rescue effort.

Vazquez is a natural writer with much to say about those trying to help in an unprecedented emergency. Among his stories is that of a man identified only as WARLOCK—apparently, a retired air controller—who seeing the chaos in air space at a Bahamian airport, improvised an air control system to help relieve congestion and provide safety for the many planes trying to take off and land. He describes the patience of the thousands waiting to leave the decimated islands and the heroic efforts by rescuers, who flew from any airport in South Florida that needed them. One incident involved two doctors who were desperate for a ride to Freeport. Vazquez describes the incident. He was talking to a person requesting help for relief workers:

“Somehow, I can’t recall why, but he then asks if we have any other seats available. There are two doctors that are also trying to get to Freeport as well. They were at the Miami-Opa Locka Executive Airport and were supposed to catch a flight from there. Something happened with that plane, and they did not get out. Again, YES.

The plane is fully loaded. Every seat is taken. This is how I like to see our planes fly. No wasted space, no empty seats. The doctors on board are young. One is a male from New Zealand, the other a female from Finland. From the beginning of these relief/rescue operations, Kim and I are in awe of the support from around the world. How the hell did a doctor from New Zealand and one from Finland end up with us on a plane going to Freeport, a place they have never been before? I ask them where they are staying in Freeport. I love the answer. Aboard a medical ship."

Vazquez filed daily accounts of such relief work for several weeks and is considering putting them together in book form.

***

It is a coincidence that Eric Barton’s piece in the October issue of Gold Coast magazine featured a novel seaplane company based in South Florida. The company, founded by a former U.S. Navy fighter pilot, already had routes established to the Bahamas, and seaplanes have more flexibility in finding emergency landing spots, especially in an area surrounded by water. It quickly responded to the transportation crisis in the Bahamas.

This company was launched a few years after another company in the seaplane business, Chalk’s International Airlines, shut down. A former military aviator also started that company. He flew in World War I and started his service in South Florida in 1919. Our only flight on a seaplane was on that airline—to the Bahamas, of course.

The combination of seaplanes and the U.S. Navy strikes a nostalgic chord, at least with those few of us who remember Lt. j.g. Tommy McCormick. Our cousin flew an OSU-2 Kingfisher observation floatplane off the Battleship Tennessee. He was killed over Iwo Jima in February 1945. The family learned little about his death, and the reason came 60 years later. A confidential after-battle report discovered by the curator of the U.S.S. Tennessee Museum suggested that he was likely hit by friendly fire from the big guns arcing their shells over his low flying plane.

So as you think about and pray for the poor souls in the Bahamas, you might remember cousin Tommy as well.

Photos provided by Peter Vazquez

One of the petty rewards of choosing a journalism career is that you usually get a free obituary. Those don’t come easily these days with newspapers scraping for every penny they can make. But newspaper and magazine writers, even undistinguished ones, usually have friends who take the trouble to note their passing, often exaggerating their contributions to the profession. We recall reading about a fellow we worked with at a small paper in Pennsylvania more than 50 years ago, who died while working for an even smaller paper. It took a few weeks, but eventually a flattering obit appeared in one of the major Philadelphia papers.

Thus it is that we belatedly announce with sadness that the author of our recent article on a young girl spending summers at Mar-a-Lago, as a family member when Marjorie Merriweather Post owned it, may never have seen her story in print. It ran in the August issue of our Palm Beach County magazines. We did not know at the time that Jennifer Rahel Conover, whose story was autobiographical, had died of a heart attack just as the magazine came out. She was 76.

Strangely, we did not learn of her death until the beginning of October, and only then because a relative cancelled the subscription in her name. There had been considerable communication between Jennifer and our editors in preparing the story. She submitted it late last year, but there were delays getting the pieces together. It took some editing (most of her stuff did), and she needed to find old pictures. When they were lost in the email system, she had to find them again and resend. But it finally ran, with an attractive presentation. The subject matter, including knowing President Trump, went beyond her childhood memories to include the story of that great estate’s seriously over budget architectural design. The piece will likely be submitted in one of the regional magazine contests, in one of the historical categories.

In view of all the work that went into it, it seemed odd that we did not hear from her after it appeared, especially after it ran again in September in our Gold Coast magazine in Fort Lauderdale. Writers usually want additional copies of their work. We were out of town for a while, but nobody contacted us and apparently there was nothing in the paper in Fort Lauderdale, where she lived. We knew her for at least 30 years and she contributed to our magazines every so often, but everyone we can think of who knew her and might have called was already gone. It’s one of the problems that come with age, although today 76 is not that old.

Her death did not go totally unnoticed, however. There was a detailed obit in the Washington Post, but we found that only after checking the internet to confirm her death. The reason it ran in Washington was Jennifer’s unusual political family history. Her father, with whom she was not close (he liked women he wasn’t married to) was a general on the staff of Gen. John J. Pershing in World War I, and later served under Gen. Douglas MacArthur.

The connection to Mar-a-Lago was through her grandfather, Joseph E. Davies, of whom she was very fond. He has been described as Marjorie Merriweather Post’s “favorite husband” of the four credit worthy men in that contest. He was an important man—ambassador to Russia during World War II and close to President Franklin Roosevelt. But she also had an uncle, Sen. Millard Tydings, and a cousin, Sen. Joseph D. Tydings, both from Maryland.

Locally, she was active in the yachting community and considered an able sailor. Writing was not her first calling. As a young woman she was a model, and later worked for the Fort Lauderdale interior design firm Rablen Shelton. The Post reported that she decorated the Nixon San Clemente and D.C. residences.

Her first two marriages ended in divorce, but she was married to Ted Conover for the last 36 years. They traveled widely, and she published travel pieces in newspapers and magazines. She also wrote a book, “Toasts for Every Occasion.” All in all, it was quite a life and deserving of at least a modest sendoff. And Jennifer, please accept our apologies for the delay.

Photo courtesy Jennifer Rahel Conover

It was in a restaurant with several TVs showing sports. There was no sound, but we knew instantly when we saw Chicago Bears uniforms and a shot of actor James Caan that this was a piece about Pic, and the old film “Brian’s Song.” It is a story that comes around every football season, and loses little of its poignancy with the years. The film, made for TV, has proved one of the most enduring works in that category.

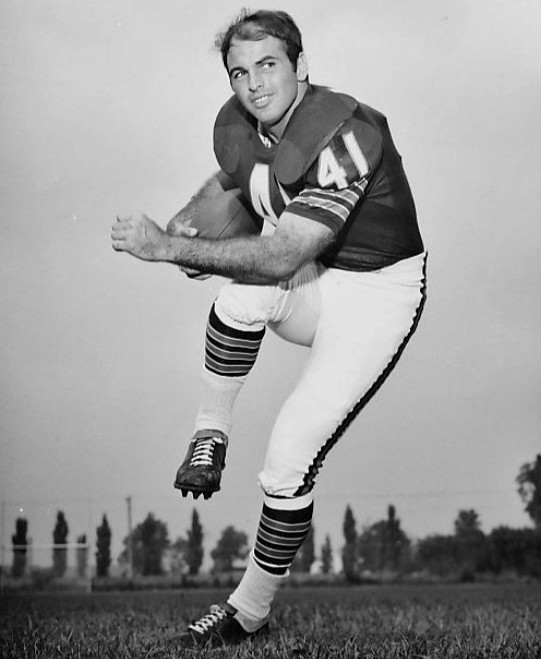

Pic was the nickname of Brian Piccolo, who grew up in Fort Lauderdale, starred for what is now St. Thomas Aquinas High and Wake Forest and died at age 26 when playing for the Bears. The film is about his close interracial friendship with his roommate Gale Sayers, the Bears’ legendary halfback who had suffered a knee injury that would cut short a brilliant career. The central theme, of course, was the early death of Piccolo from a rare form of cancer in 1970.

We heard a lot about Brian Piccolo when we arrived in town in 1971. He had been dead just a year. We hung out in Nick’s Lounge on Sunrise Boulevard a few years later, and a number of guys from the Piccolo era were patrons. Among them Bill Thies, Ed Trombetta and Bill Bondurant—all former athletes at Central Catholic before it changed its name to St. Thomas Aquinas. Over the years, we realized there was a back story to Brian Piccolo’s life in Fort Lauderdale: the unusual teammates he had in high school.

In the mid-1980s, we came to know that story better when we wrote a piece for Sunshine, the Sun-Sentinel’s Sunday magazine at the time. It was a story that wrote itself. By phone we interviewed Ed McCaskey, whose family owned the Chicago Bears. He opened our conversation by asking “What part of Philadelphia are you from, Mac?” He recognized the accent, having lived there. He got us in touch with Gale Sayers, who modestly said Brian Piccolo had kept the name Gale Sayers alive.

We spoke to Piccolo’s widow, Joy, a high school sweetheart by whom he had three daughters, and his high school coach, Jim Kurth who said Piccolo "wanted to be the richest guy on the block." We even got input from the cancer specialist who treated Piccolo, and who said his highly publicized death led to renewed research that had made a deadly form of cancer almost totally curable just 15 years later.

That story also benefitted from the recollections of Piccolo’s high school teammates who live in the area, and who turned out to be a most distinguished group. We got to know Dr. Dan Arnold, a leading children’s dentist, who loved to talk about his friend and how they competed to see who could make the most money. All who knew Piccolo confirmed his burning ambition to be successful and wealthy. He had not had a happy home environment, which friends thought motivated him to be a strong family man, with financial success.

The only teammate whose name we recognized was William Zloch, a former Notre Dame quarterback who had gotten national press as one of three brothers playing for the Irish. He shortly would be named a federal judge. Over the last 35 years he has risen to become a highly respected U.S. District Senior Judge.

Central Catholic in the early 1960s was a lot smaller than the present St. Thomas Aquinas, which has become a national powerhouse, attracting top athletes from a broad area of South Florida and transfers from other schools who value the football program’s visibility with college scouts. Piccolo’s senior year the team was a so-so 4-4. And Piccolo was not Broward County’s brightest star. That would be South Broward’s Tucker Frederickson who went on to star at Auburn and played six years for the New York Giants. But the team always had a great spirit, and in a few years it would have other measures of pride besides Brian Piccolo’s legend.

Dr. Dr. Arnold, a halfback, and Judge Zloch, quarterback, were joined in the backfield with fullback John Graham. At 160 pounds, he blocked more than ran the ball. He wound up with a long and highly successful career with Nabisco, much of the time in Palm Beach County. He is now retired in Haines City where he and his wife still operate a food brokerage business.

Piccolo, although a star, was not considered the best college prospect on the team. That was a big lineman, Bill Salter, who went to Wake Forest with Piccolo, but had a mediocre career there. Afterward, however, he became the third highest-ranking officer in the Sears organization, back when it was a formidable retail power.

The list goes on. Prominent builder/banker Jack Abdo was also on the team (“I didn’t play at all”) but was a close and deeply affectionate Piccolo friend through both grade and high school.

“Brian was a very funny guy,” Abdo says, “and there was a lot to him. He was more than a football player.”

Attorney Frank Walker did play a lot. “We all played both ways,” he recalls. “We only had 33 people on the team, and that may have included water boys. We played Lauderdale High who had 80 players.” Walker became president of the Broward County Bar Association and still gives speeches about Piccolo.

Brian Piccolo did not live long enough to see his teammates have such remarkably successful careers. But Pic, who wanted to be the richest guy on the block, was also a great friend. He would surely welcome the competition.

Last month we cited a Sunday New York Times special section detailing the decline of the newspaper business from major city dailies to small weekly papers that have served rural and suburban communities for decades. The papers that survive usually have cut staff so sharply that important stories often receive little or no coverage.

Fortunately, some independent groups, usually formed by former newspaper writers, have tried to fill the void. Some of their work has been dramatic. Unfortunately, major news outlets rarely pick up that work. A current illustration is Dan Christensen’s Florida Bulldog. The online report was started in 2009 when Christensen became one of the early casualties of newspaper cutbacks, in his case the respected Miami Herald where he was an investigative reporter.

His credits over the years are impressive. His stories brought down former powerful Broward County Sheriff Ken Jenne on corruption charges, and for years he has been following the mystery of a Saudi Arabian family that left behind its possessions in its haste to leave Sarasota just before 9/11. The wealthy family had met with some of the 9/11 hijackers. Christensen has stayed on the story despite FBI stonewalling for years. There was evidence that the FBI had investigated the possible involvement of highly placed Saudis, but had never released its information. Florida Bulldog sued to get complete records seven years ago.

Just this week U.S. District Senior Judge William Zloch, in a 95-page order that reflected considerable thought about a complex and highly sensitve matter, ruled that some of the critical records, but not all, should be released. Expect more from Christensen soon. There’s a reason its called “Bulldog.”

Another current work (and what this piece originally was about) is based on data found in a National Rifle Association report to its convention.

Marion Hammer, a longtime lobbyist for the NRA, has received handsome income from that group—$270,000 last year alone—and more than $500,000 over several years before that. However, she never filed those income reports with the Florida Senate. Lobbyists are required by law to file income reports quarterly. She could have been subjected to some very heavy fines for that failure.

You might wonder how hard Hammer worked to earn such figures. According to the NRA, she averaged five hours per week.

Christensen followed his initial May report by describing the efforts of Florida’s Republican (and pro-NRA) government to avoid going after Hammer. Those efforts include Hammer’s claim to be a “consultant” as opposed to a lobbyist and steering the matter to an obscure office rather than the usual investigative channels. Those tactics worked. As this is being written, the Sun-Sentinel reports that Hammer amended her previous reports and her case has been closed without further action or fines. It was all a misunderstanding. Hammer says she got bad legal advice, etc.

According to Christensen, there was little coverage of the incident in any of the South Florida papers. However, the conclusion of the investigation was important enough for prominent coverage in several Florida papers, including the Sun-Sentinel. What about the four previous months? The lack of coverage freed the Republican administration from public pressure to fully investigate the situation.

This story is breaking at the same time that Hammer is in the news, leading the effort in Tallahassee to derail efforts to let voters decide on a proposed constitutional amendment to prevent the possession and sale of assault weapons. In the light of recent mass murders, this is a big story. Polls show overwhelming support for such laws. About the only people opposed are highly paid lobbyists such as Hammer and the leadership of the NRA. But this one woman has shown great control over legislators. Many of the permissive gun laws that she got passed in Florida have been followed by similar measures in other states.

Those laws have contributed to the abundance of deadly military weapons that have cost so many lives. And Hammer has largely escaped censure for her role in this national crisis. But thanks for Dan Christensen’s Florida Bulldog, not entirely.

Florida Bulldog is partly a labor love. It survives on contributions, led by Michael Connelly, the highly successful crime story writer. Connelly grew up in Fort Lauderdale and attended St. Thomas Aquinas High School. One of his first journalism jobs was with the Sun-Sentinel. Although he now lives on Florida’s west coast, he remains impressively loyal to the old hometown, and serious journalism.