The Pope hadn't gotten it. The Queen of England hadn't gotten it. But the McCormicks of Fort Lauderdale got their vaccine shots last week. This is because we are extremely important and politically connected people. We also know how to jump a line.

So does Rosemary O'Hara, the highly respected editorial page editor for the Sun Sentinel. It turns out we jumped the same line, several hours apart. She wrote about it for the paper last Thursday - the day after she waited in a slow-moving caravan for three hours at a Broward County park just a day after it began offering the shots. We waited longer, about four hours, but that had to do with the timing of our appointment. And her account of how she got there at all is very similar to ours. Neither had anything to do with influence, and everything to do with timing. And luck. We both lucked onto a website that had just been blessed with access to a new vaccine outlet.

Her luck had to do with persistence, constantly trying up and down the website until it finally responded and got her appointments for her and her husband. She qualified by age, having just turned 65. Her husband qualified on stronger grounds. He suffered the effects of agent orange in Vietnam and is a cancer survivor.

Our claim is largely based on seniority, although we both have the normal abnormalities associated with vintage. But, like Ms. O'Hara, we did feel some guilt getting in line before the Pope and thousands of workers whose jobs prevent them from enjoying the isolation from human contact which is advised for those who want to survive this pandemic. We had made little effort to sign up, figuring it would be at least a month before our turn came.

But that was before our daughter-in-law went dog walking at 7 a.m. last week. She bumped into a neighbor who told her he had just gotten an appointment at a site that had just opened up and was not yet booked solid. She told our son who got on the hook, and after several calls, got through and made appointments for us both.

Our first appointment date was at 3:35 Tuesday. We were 15 minutes early and were told all vaccinations for the rest of the day were cancelled. No explanation. Our second appointment was the next day, but earlier - 12:32. If that sounds like a program timed to the minute, it isn't. We were in the line for almost two hours before a young man even checked our paperwork. When he saw we had been turned away the day before, he okayed both of us.

It was a long wait. We didn't leave the site until almost 5 p.m. But the wait was leavened by two things. First, the serpentine line of cars wound around an interesting modern looking stadium. We had never seen it, and it turned out to be the boondoggle cricket stadium which has proved almost useless. We spent time googling that history. Second, the invasion of the capitol building broke out in mid-afternoon and diverted us, and we think many of those in the long line. We started getting phone calls and emails, asking if we knew the world was ending. It made the last hour seem to go fast.

Through all this the behavior of the people in our caravan, almost all of whom seemed to qualify as 65 plus, was admirably patient. And the staff, from the kids directing traffic to the people actual sticking the needles, was uniformly cordial and helpful, even after a long day. In sum, not a bad experience, and we look forward to our second dose. But this time our experience in line jumping will be put to good use. We will figure out how to be first in line.

Meanwhile, our advice to all those trying to get an appointment: First, find an alert daughter-in-law. Second, get her a dog.

The Postal Service is under fire this holiday season, partly due to political meddling, which has screwed up established systems. As one who was once a minor part of that system, we sympathize with the little people who from the earliest days of this country have kept us in touch with each other, reliable couriers making their swift appointed rounds through rain or snow or gloom of night. It isn't their fault that Christmas cards are not moving at the usual speed. We have noted that first class local delivery, which used to be overnight, has been taking two days, and we understand out-of-town mail is even more delayed.

It makes us nostalgic for the 1950s, when almost every late teenage kid we knew counted on temporary post office work during the Christmas rush to give us the cash for family presents. We understand that temps are still used, although we haven't seen any personally. But there sure were a lot of us in those days.

We worked the last year or so of high school and through our first years of college, and by the time we were finished, we had perfected the art of gaming the system. Our first year, probably senior year of high school, we just delivered mail. We clocked on in the morning when it was still gloom of night. The sorters had worked through the night, packing bags of mail in such a way that it was organized top to bottom in the order of the homes' addresses. We were leaving with a full bag just as dawn broke.

The bags were often heavy, but we were young healthy guys. We took a trolley car to the neighborhood our route served. It happened to be near our house. It took a few hours for the first delivery, and there was no need to return to the station because a second delivery was made to a mail box, already bagged. We usually went home to wait for it, sometimes catching an hour or two of sleep. Arrival time of the afternoon shipment varied, but we were usually working again by early afternoon and finished in a few hours.

We quickly learned the tricks of our beat, such as avoiding nasty dogs. You just left the mail outside a guard fence in boxes provided by the owners. Apartments were easy because you served a half dozen families at a single stop. You quickly got to know some recipients' names. In a few cases, you delivered Christmas cards you had sent yourself. People we met on the route were almost always pleasant. They considered our work important. And we felt the same way.

By late afternoon, we returned to the post office and clocked off, ending what was about a 10-hour day. That was the first year or two. But by then, we discovered that it was possible to join the night shift, sorting the mail that arrived around the clock from the main post office in center city. The main Philadelphia post office was located practically on top of Pennsylvania Railroad tracks where cars of mail from all over arrived by rail. There it was sorted by postal zones and quickly trucked to neighborhood stations. The U.S. Postal Service was a well-functioning machine.

Sorting began in the late afternoon and went on through much of the night as trucks arrived with fresh deliveries. You got a bundle of mail earmarked for the same neighborhood and put it in slots for each address. When you had it all sorted, it was wrapped in small bundles tied up by a machine. It was fun to work.

On the night shift you got to know other temporary workers. Some had been doing it for years and were friendly with the full-time workers. They were often teachers or coaches who, like the students, had free time over the holidays. They were all pleasant fellows to spend time sorting mail with.

Working both day and night shifts permitted you to be on the clock most of the day. That was why the hours spent between day deliveries became necessary nap time. There were pauses, often brief, between clocking off and then back on. It depended on the supervisor and how strict he was. It became an understandable goal to be on the clock for a full 24 hours.

We never quite made it. Our post office had a basement where night workers often went to rest between truck deliveries. The place was pitch black, and it was easy to fall asleep there. We tried to stay on the clock during those lulls, but the supervisor used to barge in and tell everybody to get off the clock. On one occasion, we had been on the clock almost 23 hours and, hiding in the basement, thought we would finally reach the 24-hour goal. But the super came in, woke everybody up and told us to get off the clock. We did, but not more than 45 minutes later he was back and telling to get up to work.

So, postal workers, from a former colleague, we appreciate your dedication during this time of politically-inspired duress. Keep up your Yuletide morale. And stay on the clock.

The 57th anniversary of the assassination of President John F. Kennedy passed quietly last week, all but forgotten amid the health crisis and election turmoil gripping the nation. This year, however, was not without events important to the ongoing mystery of JFK's death. Two men died to whom that death was not such a great mystery. They pretty much knew who did it, and why. And both had connections to our former Gold Coast Magazine.

One of them, Vince Salandria, a Philadelphia lawyer and former teacher, died in August at the age of 92. He spent much of that long life convincing people that the official Warren Commission conclusion, that Lee Harvey Oswald had acted alone, was absurd. In fact, it was a carefully planned campaign to cover up the conspiracy between the CIA and other government leaders, including the military, to remove a troublesome president.

Among the first people he convinced was this writer, and our former magazine partner, Gaeton Fonzi. It happened in a motel in Wildwood, N.J. in the summer of 1966. Fonzi and I were working for Philadelphia magazine and were teamed up on a light story about Wildwood, a popular summer vacation spot for Philadelphia's blue collar set. Fonzi had read a piece by Salandria in a legal newspaper, in which Salandria questioned the Warren Commission's conclusion about Oswald and particularly the role of Arlen Specter, who was running for D.A. in Philadelphia. Specter had gained national attention as the inventor of "the magic bullet" theory, which held that a single bullet caused wounds to both Kennedy and Texas Governor John Connally, and somehow wound up in pristine condition on a hospital stretcher. One bullet doing so much damage was crucial to the case of a lone gunman. Fonzi had contacted Salandria, and the latter was so anxious to talk that he drove down to Wildwood the next weekend. We had developed an interest in the case, so Fonzi suggested we sit in. He warned that Salandria might be crazy.

And at first, that's what we thought. Salandria was a thin, gaunt-faced man with an almost unnerving intensity. He seemed like a fanatic. But over the next hour, he went through the evidence so methodically that we were both convinced that on an analysis of JFK's wounds alone, the Warren Commission was wrong. Furthermore, Salandria alleged the investigation had been rigged, and he knew by whom.

"Don't you see it boys, don't you see it," he said, "There's only one outfit who could have pulled this off." He meant the CIA, and if Fonzi had any doubt about that, it was dispelled in a follow-up interview with Arlen Specter.

Despite his key role, Specter had faced no hard questions about his "magic bullet" theory. He had not expected Fonzi to be so prepared to ask them, and he fumbled all over the place trying to explain his theory. Fonzi's subsequent article and other follow-up pieces in Philadelphia magazine created quite a local stir. Nobody knew it at the time, but one magazine reader who was impressed was Richard Schweiker, soon to be elected to the U.S. Senate. For purposes of this narrative, Vince Salandria makes an exit, but over the next 50 years, he grew to iconic stature, influencing the growing number of JFK conspiracy researchers. And he had laid the groundwork for what follows.

Fast forward nearly a decade. Richard Schweiker, now a U.S. Senator, was co-chairman of a committee looking into CIA abuses, including its role in the Kennedy investigation. By then it had been discovered that Chief Justice Earl Warren had had little to do with the investigation that bore his name, and it had been controlled by elements associated with the CIA. Schweiker was convinced Lee Harvey Oswald was much more than the official Warren Commission version of a lone gunman. "He has the fingerprints of intelligence all over him," Schweiker said.

He told that to Gaeton Fonzi, who he had hired as a special investigator in 1975. He remembered Fonzi's Philadelphia magazine articles and contacted him when he learned Fonzi was now in Florida, a place Schweiker suspected could prove fertile ground for research. He especially wanted to probe anti-Castro Cuban sources because Oswald had been portrayed as a Communist Castro supporter, even though he seemed to have links to CIA sources in New Orleans.

We were able to give Fonzi some help getting started, introducing him to Martin Casey, who grew up on the same block in Philadelphia. Marty had been in the Marine Corps before moving to Florida, marrying a Cuban woman and becoming fluent in Spanish. Seeking adventure, he was active in training anti-Castro Cuban-Americans and took part in some daring activities. He was trusted by the Cuban community. He was also one of the few who knew that Fonzi was working on the Kennedy assassination. Most people Fonzi interviewed thought he was part of another highly publicized probe of more recent CIA misdeeds. Many Cubans resented President Kennedy for abandoning the CIA-sponsored invasion of Cuba, which ended disastrously. They might be reluctant to cooperate.

Fonzi credited Marty with connecting him to some of the most important anti-Castro fighters. One was Antonio Veciana who had led Alpha 66, the most important group trying to kill Castro. Veciana revealed his long association with his mysterious CIA handler who used the name Maurice Bishop. Then, not knowing at the time what Fonzi was up to, stunned Fonzi by casually mentioning that he had seen Bishop with Oswald in Dallas shortly before the assassination.

It was a brief sighting. Oswald was leaving when Veciana showed up for a scheduled meeting in a bank lobby. They were not introduced, but he recognized Oswald when he saw his photos after the killing. It would have been obviously dangerous for Veciana to reveal that at the time of the assassination. Besides, his goal was to eliminate Castro, not solve a president's murder. Also, he admitted to Fonzi, people who killed a president would not have qualms about silencing him. But now, 13 years later, he helped Fonzi by working with a police artist for a sketch of Maurice Bishop. It was accurate enough that Senator Schweiker himself recognized it as David Atlee Phillips, a high ranking CIA officer who had appeared before a Senate committee.

Thus began a chain of events which has evolved over five decades. They could make a book; eventually, in fact, they did. The investigation Fonzi worked on went nowhere. Political figures close to the CIA sabotaged the House Select Committee on Assassinations. The first general counsel, a highly respected prosecutor from Philadelphia (another Philly connection) was forced out when he insisted on keeping the CIA one of his targets. Senator Schweiker, Fonzi's patron, was no longer on the committee, which was now dominated by conservative legislators friendly to the intelligence community. Several congressmen pushed to cut its funding and demanded a fast conclusion. The original counsel's replacement was an organized crime expert who did not believe the CIA would lie about such an important matter. He wanted to pin blame on the Mafia. Fonzi wasted time checking leads on the latter and wrote most of the final report which said there had likely been a conspiracy but was inconclusive as to the identity of the assassins.

Fonzi was disgusted and wrote in effect a dissenting opinion to the report he had helped write. It first appeared in three long articles in Gold Coast Magazine in 1980. It also ran in Washingtonian magazine, a somewhat sensational form that got it sued by Phillips, the CIA man it associated with the crime. The magazine won after an expensive legal fight.

Fonzi continued with his research for years, and in 1993, those articles appeared in book form titled, "The Last Investigation." He revised the work in subsequent editions. It built an impact among other researchers who cited the book as a primary source. When Fonzi died in 2012, the New York Times, in a flattering obit, called it one of the best books on the assassination.

Antonio Veciana lived longer, until this past June. He was 91. As time separated him from his CIA days, he grew more candid. At the time he told Fonzi about Maurice Bishop, Veciana would not identify him publicly - even after they met face to face at a surprise confrontation Fonzi set up in Washington. But later in life, he said Maurice Bishop was indeed David Atlee Phillips. Fonzi knew that all along and had convinced thousands that the CIA engineered the assassination.

The title "The Last Investigation" reflected Fonzi's conviction that there would not be another serious government attempt to solve the murder. But thanks to his work, and the persistent research by Vince Salandria and courageous witnesses like Antonio Veciana, that may not be the case. Last year, a group organized to pressure Congress to take a fresh look at the JFK murder, along with those those of Robert Kennedy, Macolm X and Martin Luther King.

The members of this group relating to the Kennedy's cases is a virtual who's who of the Kennedy Assassination critics. Unlike the Warren Commission and the House committee Fonzi worked for, there is no danger of CIA infiltration. The Truth and Reconcilliation Committee will present the decades of compelling evidence to a new generation of Congress. Among the members are Hollywood names such as Oliver Stone, Rob Reiner, Martin Sheen and Alec Baldwin. G. Robert Blakey, the head of the committee Fonzi worked for, is there because he regrets that he trusted the CIA. Virtually every living writer who has contributed important research is among the group.

Most infuential may be the names Robert F. Kennedy Jr. and Kathleen Kennedy Townsend, Bobby Kennedy's children. Back in the 1960s, Bobby Kennedy and his brother Ted were largely silent on the subject of their brother's assassination, although it has been learned that Bobby Kennedy quietly followed the work of researchers and may have been waiting until he became president to reopen the investigation. Having Kennedys involved is meaningful.

It is too late to punish those who designed and perpetrated JFK's murder. They are all long gone. But it is not too late to correct a massive distortion of history.

The office of vice president of the United States, long considered a job without a job, has taken on more importance in this century. President Obama called on his vice president Joe Biden's long experience in the U.S Senate in giving him work dealing with other legislators on important matters. Apparently President-elect Biden handled them well. More recently, President Trump assigned Mike Pence the job of managing the Covid 19 response team, in which the VP did not cover himself with glory. He proved much better in his secondary role of figuring how to praise President Trump at least 10 times in a 12-minute speech.

Now, however, we have found a true responsibility for Kamala Harris, President-elect Biden's vice president. It is a role the world will embrace, and likely go down as the standard for future vice presidential performance. It is a decidedly simple task - make sure that no presidential function ever competes with Notre Dame football.

That was what happened two weekends ago when one of the more epic games in college football was interrupted by NBC to bring us the acceptance speeches of Biden and Harris. It may be the only serious mistake Biden made in his campaign. Fortunately for him, the election was over and won; had this happened earlier, it could have cost him the election. The game, of course, was ND's thrilling 47-40 win over Clemson.

Clemson, a talent heavy team, was ranked number one. The gritty Irish were number four. The game was exciting from the opening kickoff, and was being hotly contested midway in the second quarter when NBC switched to coverage of the acceptance speeches. This was after NBC had promoted the classic match up all week.

There followed about a half hour of Harris thanking everybody who moves, and Biden, in a somewhat shorter appearance, mouthing the usual banalities associated with such events. The interruption was particularly irritating because of all the promo NBC had given the game. Also, the speeches were carried on several cable channels. Anyone whose distorted sense of values would prioritize a political event over a great college football game had no trouble finding a station. Not so with the football game. It is doubtful that the protest heard around the land was any louder than in South Florida, especially Fort Lauderdale. Notre Dame has an extraordinary presence here. Clemson is a big school (20,000 undergrads) and so dominant in its neck of the woods that Clemson, South Carolina was renamed (from Calhoun) to recognize it. The school undoubtedly has its own local fan base, but it can't compare locally to the Irish following.

The Notre Dame-Fort Lauderdale connection goes back almost 100 years. It began with Governor R.H. Gore, a self-made Indiana native, who built the Fort Lauderdale News (now the Sun-Sentinel) into a remarkably successful paper. He was a big ND fan and sent six of his family to the school. One of them was a founder of the very strong local Notre Dame alumni club.

The media connection lived on until recent years. Not long ago, the three dominant magazines on the Gold Coast were owned by Notre Dame grads - Palm Beach Illustrated (Ron Woods), Boca Raton Magazine (John Shuff), and Gold Coast and its related magazines (Mark McCormick).

Another big Notre Dame family is the Mauses of the Maus & Hoffman clothing stores. The three brothers who ran the company for years - the late Bill Jr. and Tom, and John, who still runs the Palm Beach store - were all Domers. There were a number of relatives and spouses who headed for South Bend at ND, or attending ND's sister school, St. Mary's College.

Another brothers combination from Fort Lauderdale are the Zlochs. William Zloch, now the senior judge of U.S. Southern District of Florida, quarterbacked the Irish in the 1960s. He was followed by his brothers Chuck and Jim, both football players out of Central Catholic High, now Saint Thomas Aquinas.

A more recent Irish influential figure is three-term Fort Lauderdale Mayor Jack Seiler. He also is vice-chair of the Orange Bowl Committee. His grandfather, Earnie Seiler, was the founder of the Orange Bowl back in 1935.

There are a few professions in which a Notre Dame grad is not prominent. In the restaurant field, Paul Flanigan founded the chain of Quarterdeck restaurants. He started out working for his late uncle, Joe Flanigan, of Flanigans restaurant fame.

The Zlochs are one of a number of Irish athletes who either grew up here or played in South Florida as pros. Jimmy Evert, father of tennis champion Chris Evert, ran the tennis program at Holiday Park for decades. He was captain of ND's tennis team in 1947.

The late Nick Buoniconti and Bob Kuechenberg were star linemen on the Miami Dolphins' legendary undefeated 1972 team. Both had distinguished Florida careers after football - Buoniconti as a philanthropic attorney and Kuechenberg as an art dealer.

Notre Dame's all-time rushing leader, Autry Denson, has deep Broward County roots. He played for Nova High and later in a brief pro career with the Dolphins. He is now head coach at Charleston Southern University.

A less well-known athlete is retired attorney Harry Durkin, who played minor league baseball. He's locally known as the former president of the large and influential Fort Lauderdale Notre Dame Club. He also has the distinction, for which he was honored by the university, of having been president of an ND alumni club in his native New Jersey.

More recently, Anthony Fasano served two stints as a tight end for the Miami Dolphins. In retirement, he founded Next Treatment Addiction in Delray Beach.

Craig Counsell had a brief but distinguished career as part of the Marlins' 1997 World Series-winning team. He now manages the Milwaukee Brewers.

Brady Quinn, who holds several Irish passing records, is now an analyst for CBS and Fox News. He is just one of many former athletes who now call South Florida home. He lives in Fort Lauderdale's Rio Vista section. As a media figure, he is a good way to return to our original theme. Let's put him in charge of the new Veep's schedule to ensure this is the last column of its kind we have to write.

Those observing the current national election drama have cited resemblances to the early 1970s. President Richard Nixon had won an easy re-election but was under pressure when two Washington Post reporters uncovered some strange goings-on in Nixon's efforts to develop negative information on his political enemies. What became the Watergate scandal began in 1972 with articles by young reporters Carl Bernstein and Bob Woodward. Woodward is the same man who, 50 years later - just last month, revealed a series of tape recordings in which President Donald Trump contradicted in a glaring way all the public comments he has been making about the virus that has killed 200,000 Americans in the last six months.

Recall also that it was tape recordings that exposed Nixon's lies in 1970 and led to demands for his resignation in 1974. Then, as now, Nixon was surrounded by operatives who helped him try to hide information, leading to jail time for several of them.

There is another parallel that has not received attention, mainly because there aren't many people around who recall the circumstances, if they knew them in the first place. It goes back to 1968 and a man named Roger Ailes. Like Woodward and Bernstein, Ailes was just a young man who knew which way was up. Ailes, dead now three years, was the same man who decades later founded Fox News, which is the next thing to a public relations agency for President Trump.

The story begins in 1968 when Nixon appeared on Mike Douglas's afternoon show. Roger Ailes was Douglas's producer for the show, which operated out of Philadelphia. Nixon told Ailes he considered TV a gimmick, and Ailes told him he would never be president unless he learned to use TV. Nixon, impressed, hired Ailes as a television consultant to his campaign against Hubert Humphrey.

The result was a campaign that has been likened to the current election. Roger Ailes had Nixon appear largely before friendly audiences, with press conferences carefully staged with planted questions. He also embraced the race card in much the same way President Trump has. It was a cynical act. It was also successful. This was all chronicled in a number one bestselling book, "The Selling of the President 1968" by Joe McGinniss. McGinniss, only 26 at the time, had already developed a measure of journalistic con. He managed to gain Roger Ailes' trust, and the latter's amazing candor made him the star of the book. If you disliked Nixon before that book, you despised him afterward. Not so with Roger Ailes. If there was a hero in McGinniss’s book, it was Ailes. Ailes is portrayed as a driving, intelligent professional who ran the guts of the campaign, the television appearances, and provided moments of amusement with his irreverent and profane observations.

Here’s one example. Keep in mind that Ailes is describing the man he was working for in the campaign, who by then had been elected President of the United States:

“Let’s face it,” Ailes is quoted in the book, “a lot of people think Nixon is dull. Think he’s a bore, a pain in the ass. They look at him as the kind of kid who always carried a bookbag. Who was 42 years old the day he was born. They figure other kids got footballs for Christmas, Nixon got a briefcase and he loved it. He’d always have his homework done and he’d never let you copy.”

Ailes was understandably surprised when he saw such quotes in the book. We interviewed him for Philadelphia Magazine in 1970 shortly after the book appeared. He had never expected Joe McGinniss to quote him with such brutal fidelity.

“Oh, I laughed like hell the first time I read it,” he said. “But I was also shocked. I thought, that dirty bastard. He really screwed me.”

Ailes soon realized the book put him on the political map. Nixon hired him as a consultant and he and McGinniss became friends. Ailes actually coached the writer for his many TV appearances over the years. Thanks to the Nixon connection, Ailes over the next three decades established a reputation as a media expert and political consultant. That eventually led to the leadership of Fox News. It was the realization of a lifetime dream.

In the 1970 interview, he hinted at that goal. Even then it was known that Ailes considered the media too liberal. He only worked for Republicans and it was known for years that his goal was to balance what he considered Democratic dominance of the media by establishing a Republican network. The goal seemed far-fetched. There was no way major network icons such Walter Cronkite (CBS), Chet Huntley and David Brinkley (NBC), or Harry Reasoner (ABC) would have compromised their principles to be party to such a partisan enterprise.

Cable news changed all that. Ailes first established MSNBC, but left when he could not control news content. Then he founded Fox News and had the freedom he sought. The result today is a network which many think made Donald Trump president and without which he would not have a prayer of re-election. It has been reported that the network molds his views, for he watches it constantly and consults behind the scenes with its opinion makers, people paid to cater to the prejudices of the network's low IQ audience.

By the time he took over Fox, Ailes was going out of his way to portray television as the most honest medium, the one in which the essential man comes through. He liked the phrase “truth television,” and he insisted that President Nixon’s 1968 successful television campaign was "the real Nixon, expertly directed and counseled, of course.”

Power corrupts. The Roger Ailes we met in 1970 was an obviously ambitious young man, but his style could appear low key, that of a pipe-smoking, reflective man. He bore little resemblance to the bulbous, often obnoxious figure who almost 50 years later brought himself down with charges of sexual harassment from Fox's female employees. He died in Palm Beach in 2017, rich but shorn of the power he relished and abused.

But, he had succeeded in his life's goal. The evil that men do lives after them.

Before peaceful protesters are permitted to pull down their next historical statue or spray paint a monument, they should be asked one question: Have you heard of Shelby Foote? Our guess is that few, if any of the people who want to rid us of unpleasant Civil War memories know the name of the man who spent 20 years writing an enormous three-volume history of that great conflict. If they have heard of him, and especially if they had read his work, they would understand the modern interpretation of the Civil War legacy does not jive with the reality of the times.

Current politicians and writers, including some who should know better, insist on using the word "traitors" to describe Southern soldiers. But that was not the word used at the time. They were called Rebels.

Foote's account of the war is based largely on what motivated the people who fought it. Despite his work, he was little known until he became the star of Ken Burns' television specials on the war. Many more people saw those films than will ever read the books. In one of his TV interviews, Foote drew a distinction between the economic cause of the war, which was obviously slavery, and the reason men fought it. They were not considered traitors so much as loyalists to their home states. It is revealing that these "traitors" were not sent to prison. Only a few Confederate leaders, including Jefferson Davis, went to prison and none for very long after it was determined that had not committed a crime.

"The average soldier on either side didn't give a damn about slavery," Foote said. He added that the southern men thought they were fighting the second war of independence; northerners fought to preserve the union. Even southerners who opposed slavery fought for the rights of their states to self determination. Most respected historians agree.

The South did not rebel. It seceded, forming a new country. There was nothing in the constitution to deal with it. From the beginning of the union, there was an ongoing argument over who had sovereignty - the federal government or the individual states. In some respects, that debate survives to this day.

It is fallacious to judge 19th century attitudes by revisionist 21st century standards. Nobody thought the war would be as long and bloody as it turned out, and men were under pressure from families and friends to fight for their states. Most common soldiers, north and south, were not moved by idelogy. They joined out of regional loyalty and the lure of adventure.

Take the case of Irish soldiers, who fought in great numbers. Some 160,000 were in the Union army. Two of them were my great grandmother's brothers, John and James Gallagher. Like most of the Irish, they were recent immigrants who fled the great famine, in their case to Pennsylvania's Lehigh Valley. Both died in the war, but they did not die to end slavery any more than southern boys died to preserve it. The evidence for that is clear. There were far fewer Irish immigrants in the south, mostly in Charleston, New Orleans and other coastal communities, but as many as 40,000 of them wore gray (if they had uniforms at all). Most recent immigrants came from the same backgrounds as northern Irish, and shared the Catholic faith and heritage, but few of them felt a moral obligation to move north to preserve the Union and abolish slavery. That was not even a goal of the Union until Lincoln's emancipation proclamation of 1863.

It is revealing that almost at the same time as the proclamation, Irish rioted in New York City. They were disheartened by the terrible casualties the famed Irish Brigade had taken in the recent battles of Fredericksburg and Gettysburg, and resented the new draft being imposed in the north, a draft that wealthy men could avoid by paying for a substitute. Rather than opposing slavery, they actually resented the freed blacks who competed with them for low paying jobs. What began as a protest against the draft quickly became a race riot, requiring federal forces to be sent to break it up. The violence resulted in 120 deaths, including 11 blacks brutally lynched, and white women who consorted with blacks assaulted. It forced half of the blacks in Manhattan to flee the borough for Brooklyn. There was even talk of Manhattan seceding from the state government in Albany.

That was the history that is being forgotten today by those making a federal case of monuments. Of all the targets of the cancel Confederate symbols movement, the Confederate battle flag is one that makes sense, only because it has been adopted by the redneck culture that embraces racism.

The argument that statues and names of Confederate leaders at various sites were designed to preserve the memory of slavery is a dubious claim. So what if squares in Southern towns featured generic statues of Confederate soldiers, that rather than being works of art, as a recent writer noted, were mass produced like fire hydrants in a northern factory. Most of those monuments went up between 1890 and 1920, the same time frame that monuments appeared in northern cities. The veterans on both sides were aging, and as still happens today with respect to World War Two, Korea and Vietnam, there was a sense of honoring their friends who had undergone the ordeal of battle.

Those who understand this best were often the officers who led both armies. Many had served together before the war and remained friends after it. Union General Grant and Confederate James Longstreet were such friends. Even though Longstreet realized the evil of slavery, he still felt duty bound to fight for his native state. After the war he supported then President Grant in the efforts of reconstruction, a stance that made some southerners regard him as a traitor and tarnished his distinguished military reputation. On the flip side, Virginian George Thomas stayed with the Union and was one of its better generals. But after the war, he was shunned by his own family.

The monument removal craze has reached extremes with attacks on the memory of Christopher Columbus and Father Junipero Serra, the latter the builder of California missions, a number of which today are major cities. Apparently neither man had an unblemished civil rights record. Perhaps the most egregious defacing was a statue of Matthias Baldwin which stands outside Philadelphia's city hall. Protesters could not find many Confederate memorials to damage in that city so some went after Baldwin. He happened to be the man who founded what was once the country's largest steam locomotive manufacturer, whose machines helped win the Civil War. He was a noted opponent of slavery; in fact he made a point of integrating his extensive work force. So much for the historical knowledge of protesters.

Copyright: © Philadelphia Inquirer)

Perhaps the final say on this issue was already said by Abraham Lincoln. He understood the reality of his times. In his two great speeches, first at Gettysburg and later his Second Inaugural Address, when he referenced the sacrifice of soldiers, he did not take sides. He did not exclude Southerners from "the brave men, living and dead, who struggled here" at Gettysburg, and when he spoke at the war's end of caring "for those who have borne the battle, and for his widow and his orphan," he did not add - except for Confederate traitors.

So, protesters, remove statues if you must, but please leave the iron frame of history standing.

We recently wrote about our first brief meeting with Don Shula. It was 1971 and in just two seasons he had turned the Miami Dolphins from a below-average team into one with a shot at the Super Bowl. We followed his team late in that season, basically the same players who a year later became a team of legend. Its 17-0 record is the only undefeated team in NFL history.

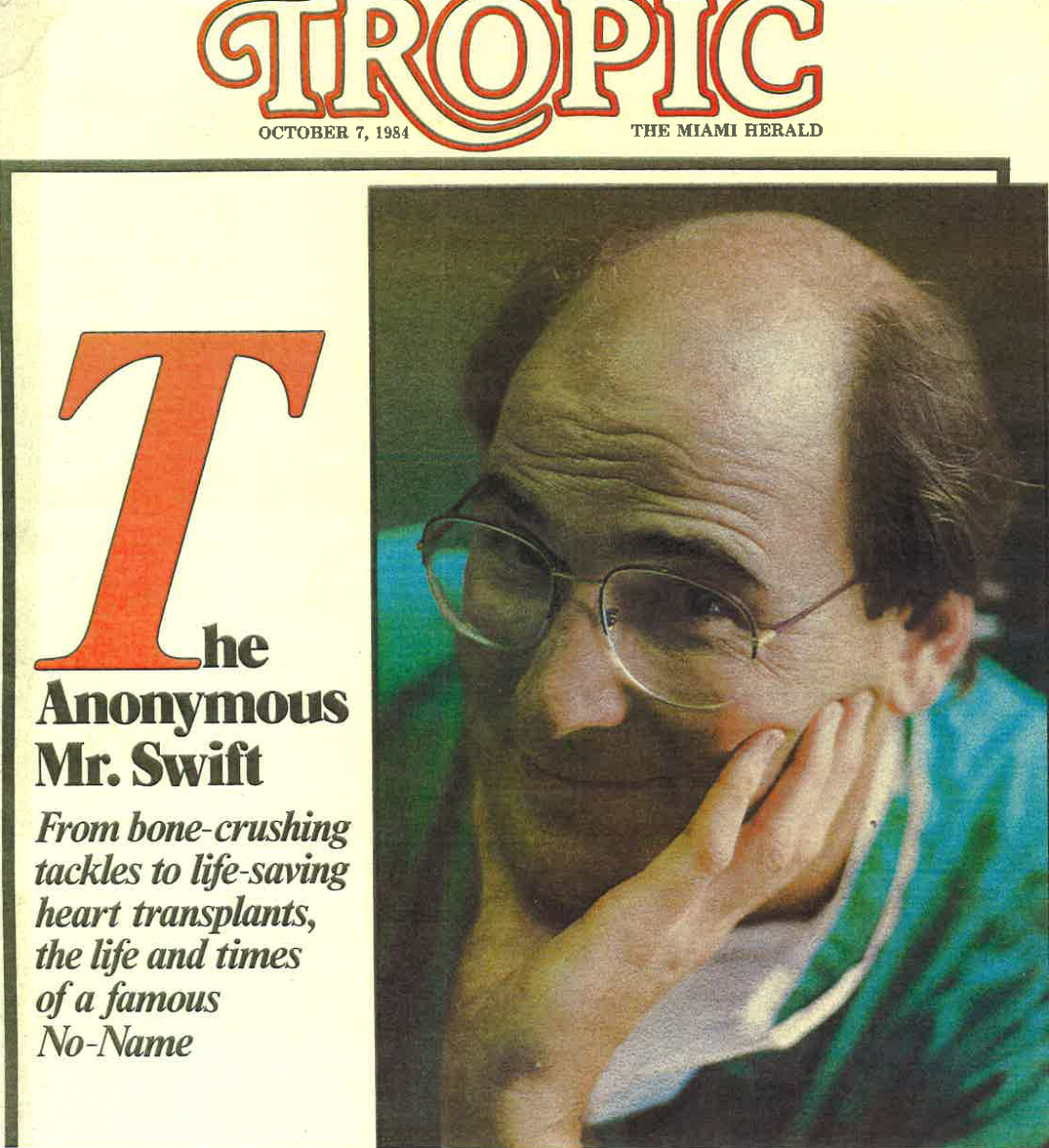

The article was not memorable, except for an iconic photograph taken on a cold December Sunday in New England. It showed a young Don Shula leading his team of destiny on the field. That story, however, led to a more interesting interview with the legendary coach years later. We had gotten to casually know one of the Dolphins' young players, perhaps the least known of the famous "No Name Defense." That was Doug Swift who had an interesting profile written about him by a young writer for our magazine.

Swift was a freak in pro football. He had attended Amherst, a western Massachusetts school known as one of the "Little Ivies." It was academically distinguished, and its sports programs rarely made national news. It was the kind of school where a top athlete might be an art major, which Doug Swift was. Swift did not think he was pro caliber and only thought about playing pro football after his coach suggested it, and the Dallas Cowboys sent a scout to check him out. He first tried out in Canada, was cut, but gained some confidence about his ability to play for money. He followed up when it was suggested he take a shot at the Miami Dolphins, who were rebuilding under a new coaching staff.

He caught an immediate break. There was a players strike and only rookies were in camp. Swift was quickly noticed. He had long hair and a mustache, not unusual today, but a contrast to the mostly close-cropped young players on that era. The late Nick Buoniconti, the recognized leader of the Dolphins' soon to be famous defense, recalled his first impression: ' I saw this big, gangling guy who looked like he should be teaching college somewhere. But as soon as he lined up on defense it was obvious he could play. I didn't know where they'd use him but I knew they'd find a spot for him."

Years later Swift reflected on that camp: "Things went well in Miami right from the beginning. I felt they liked me. I was easy to coach, and it wasn't a very good rookie group that year. Also, I could read. I think they liked me because I could read."

That type of line was common with Swift. He often spoke irreverently of the game he played so earnestly. Just three years into his pro career, he gave an interview to our magazine that was filled with amusing observations that you didn't hear from other players. Samples:

"Sometimes, even when you're not groggy, you wonder what the hell you are doing out there. You're at the bottom of a pile, and you're dressed in all that armor, the pads and the helmet, and you're sweating your ass off and you look down at that artificial grass, man, and you wonder what the hell it's all about. It sometimes seems like the pyramid thing, you know. You start thinking about that. Maybe you're just building a pyramid for somebody. It's kind of demeaning."

He resented politicians, notably President Richard Nixon, sticking their nose into the game. Also lengthy pre-game prayers.

"The bullshit that takes place on the field before the game is ridiculous. You are ready to go and then you have to go through that bullshit. It's like a bad joke. There's no need for those prayers, those invocations."

If that makes him sound bitter, Doug Swift was hardly that. He was a friendly guy, a good locker room presence, liked by his teammates. He laughed easily and his normal expression was a near smile.

But his irreverent quotes suggest that Doug Swift early on realized he had made it in football and now it was time to think about a lifetime vocation. He quit football after six years and entered the University of Pennsylvania medical school. Little was heard about him, at least from our perspective, until April 1984. We happened to be in Philadelphia and noticed a short item in a paper that a team of Temple University doctors had performed the first heart transplant in the history of Philadelphia. It noted that one of the doctors was a former pro football player, Dr. Doug Swift. To be part of such an elite surgical team was a remarkable achievement for a man just four years out of medical school. It was on a par with his football success - a rare case of an undrafted walk on becoming a starter on a good team in his first season.

We figured that story would have played big in South Florida; 12 years after their feat, the '72 Dolphins were ascending into legend. But nobody even seemed to know what happened to Doug Swift. We got an assignment from Tropic, the Miami Herald's Sunday magazine, to do the story. That story led to our second interview with Don Shula, but first the Dr. Doug Swift story. It proved to be infinitely more interesting than our first story on the Dolphins, when we followed that promising team for the last part of the 1971 season.

Dr. Swift remembered us from Florida and could not have been more gracious and helpful. We had lunch, with his beautiful wife Julie along. In response to our questions about his work, he invited us to watch open-heart surgery. We figured that would take 10 miles of paperwork and releases to set up. But he did not bother with the PR stuff. He just said to meet him at the corner where the surgical team entered the hospital. We dressed in scrubs and Swift introduced us to the men and women on his team with simply, "Fellas, this is my friend Bernie up from Florida to watch us work."

The next five hours were the easiest story we ever wrote. Dr Swift wrote it, with vivid explanations of everything he did as an anesthesiologist and quotes during various stages of the procedure. The surgery was a double by-pass of a middle-aged man, and it went perfectly We even got to take a quick look at a beating heart when the man's chest was still open. Not many writers have gotten such a front-row view of a delicate operation, especially not 35 years ago.

We learned that his job was in some ways more complicated than that of the knife-wielding surgeons. He met with the patient first and stayed with him after the operation, assuring he recovered from the very heavy drugs he had been under. Dr. Swift had to be part psychologist, keeping a patient relaxed as he put him to sleep. We watched him make small talk with the patient.

"The banter is important," he explained "It helps determine the anxiety level of the patient and relax it, as well as your own. If they recognize your name and want to talk football, that's fine. Anything to get their mind off what's going on."

The entertaining part of his personality that made him fun for his football teammates was apparent with his fellow physicians. Several times during the operation he made asides which caused their surgical masks to vibrate with obscured laughter. He also made an occasional reference to football. He spoke of the importance of double-checking equipment lined up for the surgery.

"I'm compulsive about this stuff," he said. "Arnsparger made me compulsive." The reference was to Bill Arnsparger, who coached the Dolphins' acclaimed defense of that era.

After that operation, the story was basically ready to go. There remained only to bring it back to South Florida, and that proved easy. Both Nick Buoniconti and Coach Shula not only were willing to talk about Swift, they appeared pleased to do so.

"Doug and his wife Julie really did listen to a different drummer," said Buoniconti, recalling how Swift and travel roommate Garo Yepremian always had healthy foods and fruits in their room. "Actually I love Doug Swift," he added, "He was just unique. Actually there were a bunch of unique people on that team which is what I think made us successful."

Shula recalled how much he enjoyed dealing with Julie Swift, who had gone to law school at the University of Miami and served as her husband's agent. He was not surprised at Swift's medical success.

"I knew he had medical school in the back of his mind," said Shula. "It was just a question of how long he would stay before he got on with the rest of his life." Shula even gave Swift, in his last season, permission to travel a day ahead of the team to take a medical school exam in Boston.

So where is Dr. Doug today.? Good question. He did come to a 10th reunion of the undefeated team and attended the 2013 ceremony when President Obama honored the team at a White House reception. He was extensively quoted in a 2016 piece written by another doctor. Attempts to contact him through the Dolphins were futile. We checked to see if he was mentioned in Shula obits in the Philadelphia papers. Several local coaches were quoted, but no former players. There are several listings for his practice on the internet, but the only phone that worked referred us to Pennsylvania Hospital. The young man who responded said he had no Douglas Swift on his physicians list. It did not help when we mentioned we were looking for a man who had played on the only undefeated team in pro football history. The name did not ring a bell with the young fellow.

Sic transit gloria mundi.

The deal closed in the late summer of 1970, but we didn't move down until January of '71. It took months for us to have much impact on a magazine called Pictorial Life. Like the rest of the magazine, the name was sort of meaningless, unless you counted the classy advertisers who filled its pages. We adopted the name Gold Coast in stages. It was the only name that described our market from Hollywood to Palm Beach.

We also made editorial improvements at a pace. Compared to the award-winning Philadelphia Magazine we had left, the book was amateurish. There were a few serious columns (one written by future Broward County Commissioner Anne Kolb), but most of it was advertising fluff. The design was not much better. The previous owner boasted that she never paid for a photo. In an effort to speed things up, we began doing sports features. An obvious story was the Miami Dolphins, only in their second year under a new head coach, Don Shula. They were the only professional team in South Florida. We knew Shula had coached at Baltimore, but we identified that team more with their hard-nosed quarterback, Johnny Unitas.

Shula's first year had been impressive. He had turned a losing team into a winner. His second season was going surprisingly well. By November the Dolphins were on a winning streak, and the team was drawing big crowds and getting a lot of ink, including the playful "Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid" photo of running backs, and off-field buddies Larry Csonka and Jim Kiick. We decided it would be good reading to follow the team for the rest of the season, especially since the Super Bowl was scheduled for Miami.

We were ill-prepared for the task, but that was nothing unusual. Until that fall we had barely heard of Csonka and Kiick. The only names we recognized were Nick Buoniconti, Bob Kuechenberg and Bob Griese - only because they had played for or against Notre Dame. Also Paul Warfield, because he had become celebrated on championship Cleveland Browns teams. In reading over the old story, it is clear we also had some contact with probably the biggest no-name on the now renowned "No Name Defense." That was Doug Swift, a rare pro from Amherst College in Massachusetts who literally tried out for pro football on a lark. That connection was through a young writer on our staff who had gotten to know him. He later would write an entertaining story on this most unusual football player.

With nice cooperation from the team, we began hanging out at practices, going to the home games and made arrangements to follow the team on the road. Our trips had an ulterior motive. We had other business in the north.

After a few weeks of lurking around practices and the locker room after games, Coach Shula began to notice. We had not made any effort to talk to him, and it was making him nervous.

"Don't you want to talk to me?" he asked one afternoon in the practice locker room. We replied that we intended to, but at that moment did not know enough to ask sensible questions. He was such a controlling figure that he wanted to know what strange reporters covering his team were up to. This was not a negative as far as reporters were concerned. A Philadelphia-based reporter had told us that when it came to all aspects of a coach's work, including dealing with the press, Shula was the best. And he thought the latter was an important part of being a successful coach. As his career lengthened, Shula made it clear that being a community ambassador was part of his role.

All writers covering the Dolphins saw that side of him. Sun-Sentinel columnist Dave Hyde wrote in a recent Shula appreciation: "Everyone had his home number - and he didn't just think you'd call late at night if needed. He demanded it, he wanted his voice to shape a story. He grew upset if he wasn't called."

At games, we sat in the press box near Miami Herald guys, including Bill Braucher and Herald sports editor Edwin Pope. We had learned enough over the years to pick the brains of those who knew the most about the subject.

We also spoke to out-of-town writers in Baltimore and New England. They were uniformly impressed with the newly powerful Dolphins.

Some of the glow came off the team when they lost both those road games, but they still managed to get to the Super Bowl. In retrospect, it was an amazing job that in just two years Don Shula had taken basically the same players he had inherited from a far below average team and turned them into a Super Bowl contender.

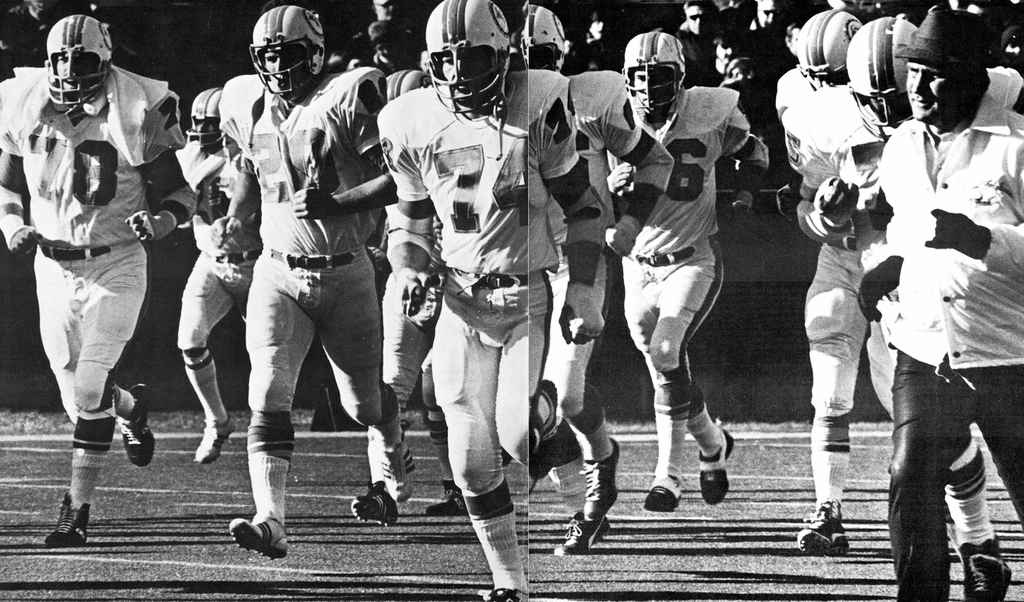

And we did get to interview Shula. Maybe twenty minutes of uninspired questions and canned answers. In further retrospect, the trip to New England had an unexpected benefit. That game was in early December and we had to break off our story in time to get it in our January issue. Later than that, it would lose impact. We had hired a photographer through friends at Boston Magazine. We just told him to work the sidelines and shoot anything that moved. When we got his pictures we were immediately taken with one, so much so that we ran it as a double page in the story.

It was an unusual shot, unlike anything we had ever seen, and as the years passed it became ever more dramatic. It is one of our favorite pictures in Gold Coast's 50-year history. It shows a young Don Shula on a cold afternoon, his game face on, leading a determined-looking team onto the field. No matter that they lost that day. It still has great prophetic impact. It depicts a coach and his team charging into legend.

And they next season they did.

Bernard McCormick had a second interview with Don Shula years later. It was far more memorable and we will discuss it in our next blog.

It was about 1975. It was our fifth year into the magazine we had renamed Gold Coast. We had been running a column by a financial fellow named John Pond. It was supposed to be about money management, but John did not tout stocks or discuss retirement strategies as much as he waxed philosophical about various subjects. It was quite a change from the columnist who preceded him, whose pieces were turgid, usually self-promotional and only appeared in the magazine because he was a regular advertiser.

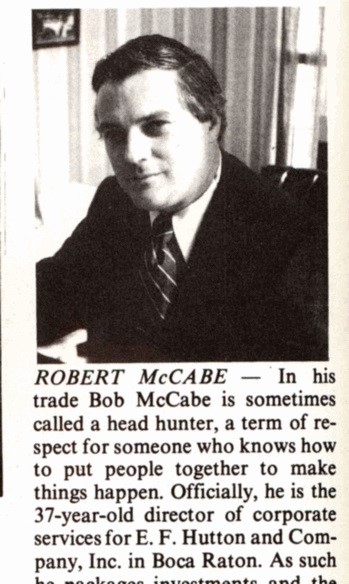

We were still getting to know our way around Fort Lauderdale. We had just become convinced that there were only a few roads from the mainland to the beach, and there were no short cuts down waterfront finger islands. We needed friends in high places and John Pond suggested we get to know a young fellow in the financial world named Bob McCabe. For reasons we have never quite understood, Bob McCabe took an immediate interest in our magazine. Realizing we were undercapitalized, it wasn’t long before he arranged a luncheon with a banker. Not just any banker. This man was president of one of South Florida’s biggest banks.

Our editorial partner Gaeton Fonzi attended. He was editor of Miami Magazine which we had acquired for a song and were in the process of building to the Gold Coast standard. Bob McCabe did such a good job of selling our story that before lunch was over the banker offered to lend us a ridiculous amount of money. He had not even seen a financial statement. It was obvious that he had not loaned our magazine the money. He had loaned it to a friend of Bob McCabe.

That story tells about Bob McCabe’s life. He branded himself “a people chemist”, if that alchemy can be enhanced by a love for witty asides and pithy comments, often colored by self-ridicule. Example: “I have never been drunk, but occasionally I’ve been over-served.” It was one of the qualities that appealed to the wealthy associates he developed over the years – a quality he preserved until the last days of his life, which ended April 21 after a battle with heart disease.

Bob McCabe was featured in a 1976 issue of Gold Coast on young people on the move.

Bob was not born to money. He came from a working-class family in the St. Lawrence River town of Ogdensburg, New York. But as a youngster getting through Syracuse University he worked summers at The Thousand Islands country club, where he became comfortable around creditworthy people and made easy friends with some of them. One of them was Milton Weir, who headed Arvida Corporation which was in the process of building Boca Raton. Weir was impressed enough with this young man to invite him in 1967 to come to Florida to handle PR for a bank he owned.

By the time we met him he was director of corporate services for E. F. Hutton in Boca. He was also a director of the Bankers Club, where the powers of the city hung out. His contacts were so widespread that the joke was that Bob McCabe had a microphone under every table at the club. There were few influential people in Boca that he did not know and become friends. For all his wisecracking, he rarely offended anyone of high rank or low.

Nila Do, a young editor who joined our company shortly out of the University of Florida, recalls that quality: “I remember having lunch in Vero Beach, and Mr. McCabe speaking with me as if I were an equal, looking me in the eye, and listening when I spoke. What I took away from our brief time was that he embraced me, the company’s new managing editor, in all my unproven ways, and that his trust in Bernie was unbreakable.”

Those people skills changed venue in 1984 when he met and soon married Eleonora Wahlstrom in Vero Beach. She was already known as one of that well-heeled community’s leading philanthropists. Much of his last 40 years were spent in philanthropic activity. The Robert F and Eleonora W. McCabe Foundation supported many charities in Indian River County, and Bob was involved in most of them. He also became an active investor. Living on John’s Island, he made important friends as effortlessly as he had in Boca Raton, connections that a decade later proved a huge benefit to our magazine.

His move to Vero coincided with a disaster for our company. A reorganization failed due to some corrupt investors and a marathon lawsuit followed. Bob was supportive through that ordeal, and when we finally regained control in the early 1990s, he worked his magical charm again. This time we expanded to the Treasure Coast with a whole new investment group. We found important people in Fort Lauderdale. Bob took care of the northern region.

Did he ever. Among those he brought to our boardroom was a CPA for Wayne Huizenga’s enterprises; a retired millionaire lawyer who was a John’s Island neighbor; a partner in the old line financial firm of Brown Brothers Harriman; and a young scion of one of the country’s foremost financial families who became southeast regional president for JPMorgan in Palm Beach. Bob himself was the logical choice for board chairman.

As anyone who has raised money for a new company will attest, quality attracts quality, and several of those initial shareholders introduced us to new investors over the years. We wound up with four people associated with Wayne Huizenga’s companies. Altogether we had 28 shareholders (not all at the same time) and every one of them got out with a nice profit. Not the least Bob.

Our son Mark had attended Notre Dame on an NROTC scholarship and had just completed six years of active duty. He joined our company as a salesman, but quickly learned enough about publishing to take over as chief operating officer. Bob served as a mentor during those early years and, although originally skeptical, supported Mark’s decision to devote funds to start a software program designed for the publishing industry – a company that has been highly successful. Bob stayed with us as chairman until last year, when he was the last shareholder to exit.

We know he enjoyed his role as chairman and he took great satisfaction in that all of his investors made a tidy profit. Still, we were surprised when his official obituary, in which he obviously had a hand, said he considered the magazine company his main business achievement.

Raised in a Catholic family, Bob described himself as a " Roaming Catholic” and did not seem overly concerned about the next world. But one thing you can count on. When it comes to the dark regions below or heavenly paradise, he knew which way was up. And if he did go above we can be sure his new best friend would be St. Peter. And he would work his way up from there.

For most of us who are newly housebroken, watching television is about the only thing we can legally do. There is justification for this, considering that we are all hungry for news about the pandemic. Also, the things we usually watch, such as sports, are not available. It is more than obvious that the TV broadcasters and their political guests are enjoying this national disaster because it gives them more exposure in a day than they usually get in months.

Some of the reporters are worse than the politicians. They make speeches rather than ask questions, and as President Trump points out, some ask questions that have no answers, or questions they know the answers to, and they only ask to get a rise out of the president. And that is incredibly easy to do. And some of them, in telling us not to panic, are panicking themselves. One prominent MSNBC woman reporter seems to be on TV day and night and always seems about to have a nervous breakdown as she describes the awful things going on. When her guests seem too composed she interrupts them, almost as if to say, “what’s wrong with you, don’t you know the world is ending?”

It makes one wish these prime time actors would study the works of Abraham Lincoln, or a more recent example – John F. Kennedy. JFK rarely misspoke and was usually concise and brief, and when the occasion called for it, quite entertaining. The otherwise admirable Andrew Cuomo, governor of New York, manages to take a half-hour to say what Kennedy would have explained in five minutes. How many times does he have to tell us not to panic, that panic can be worse than the disease, and refer to Hurricane Andrew as an example of the panic being worse than the event? Well, he wasn’t here when whole families were jammed against the doors to keep them from blowing in and taking the house apart.

Not surprising, after watching the tube all day, it extends into our dreams. We have had a recurring dream in which the reporters are as rude to President Trump as he has been to them. Just last night:

President Trump has turned over the mic to his supporting cast after having used the word “incredible” 25 times in his 15-minute ramble. Vice President Pence has spoken. Then the President asks “any questions?”

Reporter: Yes, but you shut up and let Dr. Fauci speak. Doctor, we won’t ask the same stupid questions you have been getting every day, and to which you give the same patient answers. We notice you went to Holy Cross. Now Holy Cross has many famous grads, but most of them are tall. Bob Cousy, Tom Heinsohn and Chris Matthews come to mind. You, however, seem quite small, at least standing beside that fat Mussolini. We wonder if back in the day you were the coxswain on your school’s crew? I think of that because I was a coxswain in high school, only weighed 75 pounds as a freshman. We got to know Kel – that’s Jack Kelly, our national singles champion, whose sister Grace went on to become a famous movie star and princess. We sometimes saw her hanging around Boathouse Row. We only knew her as Kel’s good looking sister. Now our guess is Holy Cross didn’t have a crew back in the 50s when you went there, and we doubt if they had a horse racing team, so you couldn’t be a coxswain or a jockey, and you had to become a world-renowned epidemiologist. Right?

President Trump: Tony, don’t bother with that nasty question. Let me...

Reporter: I told you to be quiet. I have a question for Vice President Pence. Mr. Vice President, You just spoke for 11 minutes and only mentioned President Trump 16 times, breaking your record of 14 said yesterday. Now, don’t you think you should give the president a little credit? And you probably know what happens to people who don’t suck up to him…

President Trump: That’s a nasty question, designed to hurt my re-election...

Reporter: You be quiet. But I do have a question for you. You are obviously under tremendous pressure. Your face is as orange as your hair. How do you relieve the pressure? Are you getting anything strange?

President Trump: That’s a good question. I was noticing that incredibly well-built reporter in the back, the one with the funny accent. I may give her a personal int … WAIT THAT’S A NASTY QUESTION! YOU ARE TRYING TO ENTRAP ME! Well, that won’t work, I’m too smart for that. You are an incredibly terrible reporter!

At that point, all that shouting woke us up. We tried to get back into the dream, but no luck. So all we can do now is to remind everyone that for the duration of this crisis, whatever you do, don’t panic. But If you must panic, panic calmly.

If that doesn’t work, boil some water.