Harry Rosenfeld (right), as remembered by The New York Times, with Ben Bradlee (left) and Dustin Hoffman (middle) in 1976.

Harry Rosenfeld's recent death prompts a discussion of the then and now in American journalism.

Harry who?

Think back to the award-winning film All the President's Men in which Jack Warden portrayed him. It was one of a number of excellent performances, including Robert Redford as Bob Woodward, Dustin Hoffman as Carl Bernstein, and Jason Robards as Ben Bradlee. The Washington Post stories resulted in the resignation of President Richard Nixon. If this doesn't ring a bell, stop reading. You won't get what's coming.

Rosenfeld was the assistant managing editor of The Washington Post who supervised young reporters Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein when they stumbled on the Watergate story, which ranks among the best that American journalism has to offer in the last century. He supported his reporters when managing editor Ben Bradlee, realizing the magnitude of the story, wanted to replace them with more experienced reporters.

The Watergate scandal began in 1972, and here is the connection which relates to today. The event occurred not long after I interviewed Roger Ailes for Philadelphia magazine. Ailes was a communications advisor to President Nixon. He got that role after he coached Nixon in his winning presidential campaign of 1968. Ailes was prominent in Joe McGinniss' best-selling book, The Selling of the President 1968. He came across as very smart, very amusing, and very unscrupulous. Ailes was based in Philadelphia at the time. He was producer of Mike Douglas afternoon talk show. In our interview, Ailes defended his presentation of Nixon as fair and balanced. It wasn't. Press conferences were stacked with friendly reporters who asked only softball questions. It was contrived at every turn. Exposing that is what made McGinniss' book a sensation. Ailes did admit that he thought the media was biased in favor of Democrats, and said he'd like to see a Republican outlet to balance the three major networks. I barely mentioned it in the piece; it seemed so far-fetched. But two decades later, after he rose in television status, Ailes saw his opportunity in cable TV. He started Fox News and stayed as its head until forced out by a sex scandal in 2016.

When The Washington Post first went after President Nixon, it was alone. Other media, print and broadcast, largely ignored its stories. Eventually, however, as the evidence mounted over two years (tapes were discovered proving Nixon's heavy involvement), the rest of the journalism world joined in. Prominent Republican politicians sealed his fate when they came to believe that using CIA operatives to spy on Democrats, and then lying to cover it up, was a very serious matter. Men like Republican Senator Howard Baker of Tennessee, Democratic Senator Sam Ervin of North Carolina, and Republican Attorney General Elliot Richardson put their reputations on the line by respecting the Post's reporting. Richardson resigned rather than obey Nixon's order that he fire the lead Watergate prosecutor. Ultimately there was little support for Nixon among his own Republican colleagues.

But imagine if now were then, and Ailes had launched Fox News in 1972. Suppose, for two years, it brought on guests, including elected officials, to say Watergate was a hoax and a plot to get Nixon. And every time a negative Nixon story broke, the network switched the subject to President Kennedy having chased girls or the seemingly endless Vietnam War or some other "false equivalency." Suppose this network did not cover Watergate at all, or only when it figured out a slant that defended the president and made a large number of Americans believe that there was nothing wrong with using the CIA to spy on political opponents, and lying about it under oath. Suppose men like Baker, Ervin, and Richardson said nothing, or voted not to pursue the matter in any way. And suppose their silence was applauded at every opportunity by a well-watched network.

The difference between then and now is media treatment, and a Congress filled with Republicans who would throw men like Baker and Richardson out of the party. And attack Harry Rosenfeld and his newspaper as enemies of the people.

It should be noted that Nixon’s transgressions, so shocking then, now seem like venial sins compared to the gravity of trying to overthrow a presidential election and helping incite an attack on the U.S. Capitol.

Congratulations Harry Rosenfeld and The Washington Post for your journalistic courage. And also recognition to Roger Ailes for proving that the evil men do lives after them.

The McCormicks were honored to be part of the television presentation marking the 100th anniversary of St. Anthony Parish, Broward County’s oldest Catholic church. Compared to some Fort Lauderdale families who date almost to the beginning of the parish, we are newcomers — only 50 years. We are perhaps unusual in that we remain in the same house we bought in a hurry in 1970, and have had four kids and six grandchildren attend St. Anthony.

It was all quite accidental. Moving into a new state and a new magazine, we did not have time to house hunt. Most young families were settling out west in Plantation and Coral Springs. The old neighborhoods in east Broward were out of favor with the younger crowd. Accordingly, Peggy began asking Catholic schools in Plantation if our three young kids could get in. She was amazed to hear one school had a three-year waiting list. We had never heard of a waiting list for a Catholic grade school in Philadelphia.

When she asked if there was any Catholic school they could get in, it was suggested we try the old school downtown — St. Anthony. When we learned there was no waiting list, our house hunt shifted east and was quickly solved by the delightful Martha Brown of L.C. Judd & Company, who had, in her words, “the perfect” house for us. She was sure right. Fifty years later we still live on a quiet street in the historic Colee Hammock neighborhood. It combines well preserved old cottages such as ours, built with durable Dade County pine, shaded by ancient oaks, with some spectacular (and expensive) new structures occupied by some of the city’s leading citizens. And St. Anthony found us that location.

We did not, however, want our kids in St. Anthony just for the convenience. We wanted a learning environment we both knew well, a safe and orderly classroom experience, hopefully instilling the values we shared, and presumably shared with all the parents in the school.

We found that, and much more. On the first day of school the first young mother we met was Jane Hearne. She was the former Jane Maus of the Maus & Hoffman men’s clothing family. They had created the modern Las Olas Boulevard when, in 1940, the original William Maus led a group of merchants from northern Michigan to establish winter operations in Florida. At least 10 stores followed that company south. That first meeting led to a relationship with three generations of one of the town’s most prominent families. That relationship led to a trip to Petoskey, Michigan, to see (and write about) where all these businesses had their start.

It soon became obvious that we had found in St. Anthony a trove of Broward County’s leading citizens. We learned that Brian Piccolo, newly dead and not yet memorialized in the film Brian’s Song, had gone there. Also Chris Evert, still in high school when we arrived but already a national tennis figure. The Gore family, which was still running the Fort Lauderdale News (now the Sun-Sentinel) had strong connections to the school. The family of E. Clay Shaw, Fort Lauderdale’s mayor in the 1970s, and later a longtime U.S. Congressman, was a member of the parish. Jack Seiler, who became mayor several decades later, was a student in the school at the time. The Thies family, of beer distributor fame, were parishioners. Many of the pioneer families have had two, and in some cases three generations (going on four) associated with the school. Mauses, Camps, Buckleys, and many others have added new waves of students to the school.

Over the years our family was no more active in parish activities than dozens of other families, but we were privileged to be selected by the then Pastor Timothy Hannon (one of several Irish born pastors over the years) to have our daughter Julie among the small group of children who met the Pope at the Miami International when he visited in 1987.

The anniversary TV presentation included remarks by Father Michael Grady, St. Anthony pastor, who has built a reputation as a master of short, trenchant homilies (rarely longer than three minutes) and Sister Therese Margaret Roberts, age 94, who said she remembers the building opening. She taught at the school for decades.

Key participants in the video, and most deserving, were members of the Camp family. James Camp II was in the same class as Sister Therese. He joked about her catching his passes in gym class. His father was one of the earliest parishioners, arriving in 1925. He helped launch Broward’s first bank after they all closed in the troubled 1920s and became a statewide figure in the financial industry. James II became a lawyer and was joined by his son, also James, in the law firm.

“My dad is 93, and was baptized here,” Jim Camp III said. “I’m one of five, and we were all baptized here, as well. We’re members here with the school, went on to St. Thomas Aquinas, and I have five children, and they were all baptized here.”

“I hope that it’s always here,” he added. “I guess I’d like to see some of my grandchildren to continue part of their life here as well.”

The graceful St. Anthony Church opened in 1948, replacing the original smaller church on Las Olas Blvd., which moved to 3rd Ave. and became the First Evangelical Lutheran Church (above). Only recently, it closed and is slated to become a restaurant nightclub.

It did not make it into the TV interview, but we contrasted our Philadelphia experience with St. Anthony’s legacy. In the 1950s we could walk to three Catholic grade schools and had a short ride on public transportation to reach several more. All but one of those schools are gone, and in several cases even the parish churches, beautiful old structures, have closed. On the other hand St. Anthony is close to its capacity of 490 students. Its affluent surrounding neighborhoods and the explosive growth of downtown assure the school continued support.

St. Anthony not only continues to thrive. It is still growing. The parish used its 100th anniversary to launch an ambitious expansion of the school and a parish social center. Come back in 100 years to see how that worked out.

The proposed and much-debated infrastructure bill includes money for Amtrak improvements, quite a contrast from past budgets when Amtrak was routinely starved for funds. Part of the proposals for Amtrak is fast intercity trains, connecting major cities with other population centers that are too close to warrant airline service. The Acela train on the northeast corridor proved the concept. Such trains are being considered all around the country, especially for major markets such as Chicago and L.A. Some are already in service.

Locally, Brightline is a good example. Although currently suspended due to the pandemic, it has already proved itself as a fast way to navigate the Gold Coast from Miami to Palm Beach, and should really show its value when extended to the Treasure Coast and eventually Orlando. These new railroads are not conventional commuter trains. Tri-Rail has stations every three miles, but the intercity concept puts stations 10 or 15 miles apart. They are meant to be a quick ride.

To implement this fast train concept, existing railroads will have to be improved for higher speeds — in some cases entirely new tracks unimpeded by grade crossings. Such plans are being considered for a new service from Atlanta to Nashville by way of Chattanooga. That revelation brought to mind an idea we have promoted for almost 50 years: an expansion of the successful Auto Train concept.

The obvious move is a Midwest train, using the existing Sanford station as its Florida terminus and somewhere in the Indianapolis area as its northern. The concept is not new. In fact, it was tried, back before Amtrak took over what started as a private company. That was in the mid-1970s. Auto-Train Corporation had introduced its northeast service so successfully that after riding it a few times, we were so convinced the idea would sweep the county that we bought stock in the company.

The move to serve the Midwest made sense, especially when the train was combined with a regular passenger service. Alas, the execution was poor. Railroads in general were under pressure at the time, and the quality of many routes in the Midwest had deteriorated, slowing speeds and creating hazards. The host railroads even warned Auto-Train Corporation that its locomotives were too heavy for the substandard tracks.

The new service barely had a chance to prove itself when a serious derailment caused the train to be suspended. The legal problems that followed caused the whole corporation to fail. Amtrak discontinued its conventional Chicago-Florida train in 1979. But the concept of loading cars on trains was sound, and after a few years Amtrak took over the northeast Auto Train and has run it to this day. It is one of the few Amtrak trains to almost pay for itself.

The idea of a Midwest auto train comes up periodically, but now, with the possibility of rebuilding the rails it would use, it is tempting to make a real push. Combined with a conventional long-distance passenger train, it seems more than feasible.

The trick is to combine the best features of the proposed intercity trains with the established Auto Train. It would begin in Miami and serve the present Amtrak stations in South Florida. There are five between Miami and Palm Beach. But once it hooks up with Auto Train in Sanford, there should be only a few stops at key locations — South Georgia, Atlanta, Chattanooga, Nashville, Louisville. Those few minutes delay will not be important to Auto Train patrons, but should add considerably to ridership, and the bottom line. That kind of schedule would work well as a connection with the intercity trains being planned.

The same applies in the north. After Auto Train disconnects somewhere south of Chicago, the conventional Amtrak section could continue on to Chicago and the Twin Cities or Milwaukee.

Initially, this train need not be daily. Schedule what the traffic will bear. Auto Train users, and Amtrak long distance riders in general, do not make spur of the moment travel decisions.

A Midwest auto train made sense 50 years ago, but it was badly executed. Now seems the time to do it right.

With everybody staying home so much of the last year, we all saw a lot of TV interviews on all manner of subjects: politics, sports, civil rights, finance, religion, and sex, to name a few. Regardless of the topic, we heard repeated use of creative terms as we recognized the intersection of the existential and systemic influences on the conversation.

We have been in this rodeo before, and without getting over our skis and spiking the ball ahead of our pay grade, we invariably dreamed we were involved in one of these interviews. In this dream, we were both asking and answering the questions. For ease of simplicity, we refer to these roles as Q (for questions) and A (for answers).

Q. Thanks for joining us to talk about this existential reality. You know the rules. We belong to the Larry King school. We never read a book before we do an interview in order not to prejudge our guests. We will ask only questions we know the answers to, and if we don't like your answer, you can thank me for having you on the show and go home.

A. Right, and you know I'm only here to promote my book. Whatever you ask me I will turn my answer into a plug for the book.

Q. Roger. And what do you think of the world today? Do you recognize the existential presence of systemic systemicism?

A. Maybe I can deal with that in my book.

Q. And what is your book actually about?

A. I don't know. I haven't read it.

Q. I thought you wrote it.

A. Ask not what your country can do for you. Ask what you can do for your country.

Q. Isn't that from a JFK speech? What does that have to do with your book?

A. President Kennedy didn't write those lines. Everybody knows Ted Sorensen wrote his stuff. Nobody writes their own books today. But I do intend to read my book. I've been running around with the NBA playoffs, Stanley Cup, and Trump's new Twitter stuff. But I will find time.

Q. What about the bipartisan issues? People want to know where you stand.

A. I'm working on that seven days a week, 24 hours a day.

Q. That's a lot of time. Does that count the afternoons I see you chasing broads in Las Olas bars?

A. No, that's on my own time.

Q. You obviously manage your time well.

A. Any man who can't handle his job in two hours a day is in over his head.

Q. Is that another Sorenson quote?

A. No, that's my Uncle Chris. He divided his time between selling real estate and the track.

Q. Well, our time is up. We just have time for a half hour's worth of commercials. We'll ask if you get lucky in our next interview. Thanks so much for casting light on this important subject.

A. It is always a pleasure to discuss existential indigenous tribalism. I look forward to dreaming another book with you.

The most outlandish proposal was to rebuild the Atlantic Ocean near Weston. The second was to build a tunnel from Broward Boulevard to the beach. We deemed both ideas absurd solutions to the problem we were addressing, which was the mounting congestion on and near Las Olas Boulevard, Fort Lauderdale's oldest and most heavily traveled path from the mainland to the beach. These preposterous proposals were intended as a preface to a complaint about the ridiculous overbuilding in downtown Fort Lauderdale. The increasingly heavy traffic already created a traffic mess that will only get worse when (and if) all the too tall buildings under construction are completed and filled with new residents. Why does the city approve developments that welcome new residents while damaging the quality of life of those already here? The worst bottleneck is Las Olas, which the city proposed narrowing, a move that would only make living in the old neighborhoods around Las Olas increasingly unpleasant.

We shouldn't have deemed our ideas absurd so fast. On the same Sunday morning we began to write these thoughts, The Sun Sentinel carried a front page story titled: "Tesla tunnel to the beach may not be a pipe dream."

The story appeared incredible until we saw quotes that showed influential people were taking the idea seriously. The most catchy name was Elon Musk, who was known to do impossible things. The tunnel would be built by Tesla's Boring Company, which already built a similar tunnel on the West Coast. The quoted cost of the 2.6 mile tunnel was surprising low, compared to the proposed cost of bridges to eliminate the drawbridge crossing where the FEC Railway tracks meet the busy New River.

Fort Lauderdale Mayor Dean Trantalis was quoted as intrigued by the idea, as were other community leaders, including Mary Fertig, a respected neighborhood activist who lives off Las Olas in the Idylwood development. The catch? This tunnel is not the Henry Kinney Tunnel that carries cars under the New River on Federal Highway.

It would not be for cars. It would be two lanes, only 12-feet wide, which would convey a transit car capable of great speeds. It would begin at the new Brightline rail station on Broward Boulevard and end at the beach with stops along the route where passengers could exit and use elevators to reach blue sky.

Useful? Of course, but how useful would depend on how many commuters between the beach and downtown require their cars during work hours. Tourists obviously don't, but many of those now jamming the rush hour roads funneling into to Las Olas are workers, coming and going in all directions from Downtown. They need cars just to complete their daily commute, not to mention work-related trips.

Since the idea of a tunnel is considered feasible by informed parties, why not recognize the Age of Biden and think bigger? Much bigger. How about a combination of the futuristic rail tunnel and a conventional tunnel carrying cars and other standard vehicles? It would be a big job indeed, but it would be a solution to a traffic problem that until recently appeared unsolvable.

The location was ideal, on the corner of one of the busiest intersections in the old Philadelphia neighborhood of Germantown. Chane's pharmacy (we called them drug stores in those days) was surrounded by other active businesses. There was a popular bar across the street, a super market just a half block away, and a high-end candy store just a few doors down.

There was a busy shoe repair store close by. The second floors of the buildings housed offices, including dentists and lawyers. There were two large grade schools a few blocks away. Students passed the pharmacy on their way home. They often stopped in to enjoy the soda fountain. The year was 1951.

Our friend Tom McGill, who worked there as a soda jerk, recalls meeting the owner and his wife. We don't, but we understand the senior Mr. Chane was ill and may have died about that time. But we did know his son, Marvin Chane, who appeared to be running the place when he was only 19. He was a good looking, personable guy, and seemed to be a savvy young businessman. We saw him when we dropped by to visit Tom McGill, which was often. In fact, we had hoped to get the job as a soda jerk when Marvin hired Tom. Our problem is that at age 14, we were only 4'11" tall, one of the smallest boys in our high school freshman class. Tom McGill, although a few months younger, was about a foot taller. Marvin thought we were too short for the fountain counter. He hired Tom.

Tom liked to tell the story about how he left the job after about a year. He liked Marvin Chane and enjoyed his job, but money is money.

"I was making 55 cents an hour," he recalled recently. "I had a chance to earn 75 cents working at a Sears auto store, changing tires and stuff. I asked Marvin for a raise. He said no and tried to talk me into staying, pointing out that I would have to spend carfare to get to the Sears store in Jenkintown. But I did leave."

McGill recalled the incident when informed of Marvin Chane's death at age 90 earlier this month, after a long battle with Parkinson's disease.

We are not sure how long Marvin Chane ran the pharmacy. In the next decade, the neighborhood went down. Most of the good stores closed. Thousands of families moved. Today, you can hardly recognize the intersection. It is a place where you make sure your car doors are locked when you stop at the light. We think he sold out before things got really bad. He was, as we said, a good businessman.

If the Germantown pharmacy was a good business, his next move was an apparent gold mine. He owned a pharmacy downtown, in the high-toned Rittenhouse Square area. He probably had that property for most of the 1960s, but we don't recall seeing him during that time. The next time we heard his name was when our managing editor at Gold Coast Magazine began dating him in the mid-1970s. By then, he was a co-owner (along with his cousin Marvin Himelfarb) of the Bahia Cabana in Fort Lauderdale. They were known as Big Marvin and Little Marvin. They turned an obscure non-descript little hotel located on the south side of the Bahia Mar Marina into one of the most popular waterfront hangouts. It took advantage of the great view of the active marina, which was separated by only a narrow inlet. That location is what prompted Chane to make the purchase.

In the process, they pioneered open air waterfront bars. That is according to Bob Townsley, who had a 50-year career as a bar manager on the Fort Lauderdale beach. Townsley worked with Chane during the early days of the Bahia Cabana.

"The bar there was indoor," recalls Townsley. "One day Marvin said to Little Marvin, 'What would you think about putting the bar outdoor near the water?'"

The bar soon became a reality. It was a round bar, and the owners also rebuilt the small dock with tiered seating leading down to it. Thus began a 28-year ride as the bar attracted a steady crowd. According to Bob Townsley, it also inspired numerous places with waterfront views to put in open air bars. It was sold in 2000 and closed after serious storm damage in 2017. A major development was recently announced for the site.

We are sure that during our many visits, sometimes with our young family, we brought Marvin up to date on Tom McGill, who retired early in New Jersey after a successful career in marketing. Tom became a valued shareholder in our magazine, and we saw him when he spent part of winter months in the Naples area.

On one of his visits to Fort Lauderdale, we decided to have some fun. We arranged through Marvin's girlfriend, our editor, to go to dinner with a visiting couple. Neither couple knew who they were about to meet. That meeting was in the lobby of Bahia Cabana. I simply said, "You people know each other, don't you?" The couples looked at me strangely. "Don't you know each other?" I repeated. Marvin Chane broke the awkwardness by extending his hand to Tom McGill. "I"m Marvin Chane," he said, and I heard Tom, almost beneath his breath, slowly drawl "M a r v i n C h a n e," and then introduced himself with a great smile.

There followed a fun dinner with a lot of reminiscing about the old Philadelphia neighborhood and both men telling stories about their respective careers. Toward the end of the dinner, after a few drinks, Tom brought up the subject of his leaving the soda jerk job in 1952 when Marvin wouldn't give him a 20-cent raise. To our amazement, something of an argument broke out, with Marvin making the same arguments about the time and carfare involved with Tom taking the suburban job. This did not rise to the level of a lawsuit when both men realized the absurdity of rehashing an incident from almost 50 years ago. A happy good night was had by all.

The incident does illustrate, however, the quality that made Marvin Chane such a success in two very different careers a thousand miles apart. Once a businessman...

The Declaration of Independence had 45 signers. Only two had distinctly Irish names: Charles Carroll of Maryland and Thomas Lynch of South Carolina. And, there was not a single signer with the first name of Sean, Patrick, Kelly or Ryan. Such was the Irish influence (or lack of it) at the nation's birth date. Four score years later, there was a huge wave of Irish immigration prompted by the famine of the 1840s. Multitudes of half-starved Irish arrived in the U.S. determined to become good Americans. They proved it by volunteering in huge numbers for the Civil War and gave history a record of valor exemplified by the legendary Irish Brigade.

Now, a century and a half later, they celebrate St. Patrick's Day with the knowledge that they have not only become Americans, they have made America Irish. At least that's the impression one gets if you go by the names Americans proudly wear. Unique among the various nationalities who compose the American mix, the Irish have their traditional names adopted by other blood lines. For some reason, not too many babies are being named Cuomo, Brezenski or Spoelstra.

Part of the reason is that many Irish last names have been adopted as first names. Of the top 10 Irish family names in the U.S., six of them have served as first names. Among the most common are Kelly, Ryan, Brian and Neil, the last two variations of O'Brien and O'Neil. Less frequently found are Murphy and Conner. Going deeper on the list of Irish surnames produces an abundance of names which have appeared as first names. Riley, Quinn, Brady, Donovan, Nolan, Duffy, Carroll, Casey - the list goes on.

This is a fairly recent trend. Growing up in a neighborhood and going to schools with a number of Irish families, we knew only one person with the first name Ryan. It appears the name came into common use when Ryan O'Neal became a well known actor in the 1960s. Today, it is popular with both sexes. You hear it every day.

A newcomer to the last-to-first names club is one familiar to our family. Cormac is beginning to appear as a first name, partly thanks to Pulitzer Prize winning novelist Cormac McCarthy. He actually changed his name from Charles to Cormac. The name illustrates the full-circle trend of Irish names. Cormac is derived from medieval Irish kings and prominent clergy. In that time, Irish only had one name. When second names were introduced, many Irish who had taken a royal name became McCormick. That happened with all the Irish names beginning with Mc or O. Those prefixes simply mean "son of" or words suggesting a family lineage.

This is only half the story. Traditional Irish first names have become so common among other ethnic groups that some of the most popular, such as Sean, Kevin and Barry, have lost their brogue. But, there seem to be new ones waiting in the wings. Liam, the Irish form of William, owes increasing use to the actor Liam Neeson. And rarer names, such as Colin, Aidan, Eamon, Dillon, Seamus and Shane, are gaining in numbers.

Irish names for women are also common. We already mentioned Kelly and Ryan. Then there's Caitlin, Cara, Maeve, Shannon, Deirdre, Fiona and Shauna, all beginning to creep into common use.

These rarer names are often Irish versions of English names. Sean is John, Seamus is James, for instance. Those names normally emigrate to the U.S. with Irish families anxious to preserve their heritage. But once they are attached to a prominent person, they tend to go mainstream. We find no research explaining this, but our theory is that ethnic groups with surnames that are difficult to pronounce pick Irish first names, not because they are Irish, but because the names strike them as solidly American.

The irony is that original Gaelic names were at least as difficult to the Yankee ear as any European or Asian name. For example, Kennedy is the English translation of Ó Ceannéidigh. For reasons lost to history, emigrants from the Emerald Isle had the good sense to translate them to English spellings as they found their way across the seas. If they hadn't, maybe today we would be naming babies DiMaggio.

Organized crime has a long and colorful history in South Florida.

Going back to the 1920s, the archives are filled with stories on which mobsters lived or vacationed here, where they chose their homes, what restaurants they favored and with whom they associated. But one of the most interesting stories about the wise guys in South Florida is one that never happened. It is how police prevented one of the most violent mob families from setting up their deadly business in Broward County.

If it remains a largely untold story today, it is because it got very little publicity when it happened more than 30 years ago. That lack of public knowledge goes to the essence of the tale. The investigation that has a unique place in American law enforcement - resulting in the take down of an entire Mafia family - succeeded largely because of its secrecy.

It began in 1983. Police agencies were aware of a growing organized crime presence in South Florida. A number of Mafia families were active here, but their activity was largely non-violent and there were no territorial disputes which periodically bred violence in northern markets. Florida was considered open territory. Mobsters came here for the same reason as everybody else - sun and fun. They did not choose to bring attention to themselves by killing each other here.

Local police departments wanted to keep it that way and were concerned that they needed a better method to monitor the various Mafia families who had a presence here. One of the problems is that local forces did not communicate well, either with each other or northern jurisdictions, whose organized crime units sometimes knew more about what was going on in Florida than local police. Thus, the Metropolitan Intelligence Unit was born.

It consisted of representatives of four local police agencies, plus the State Attorney, Justice Department, the Broward Sheriff. It had close contacts with several departments from northern states. The man who headed it was Douglas Haas, who had been a Fort Lauderdale homicide detective. The affable, articulate Haas was better known for the few years he had done off-duty security work at the popular Bahia Cabana Hotel than he ever was as MIU head. But that was no accident. He wanted it that way. A rare Sun-Sentinel story about MIU in 1987 quoted former Fort Lauderdale Police Chief Ron Cochran:

"It's not a glamor group going out to make arrests," says Fort Lauderdale Police Chief Ron Cochran, a member of MIU's board of directors. "It has always been behind-the-scenes work. The arrests go to other agencies."

That story was written by Michael Connelly, who had a fascination with police work. That interest shortly led to his move into writing crime story fiction, at which he has become a widely known best seller. Connelly also wrote one of only two stories about MIU's biggest score - the investigation which brought down the dangerous crime family.

In 1985, MIU was just getting its bearings when Doug Haas picked up a tip from a Pennsylvania organized crime source that the Nicky Scarfo was setting up business in Fort Lauderdale. That was not just news; it was alarming information. Scarfo headed the Philadelphia/South Jersey crime family, which had built a reputation as one of the most violent in Mafia history.

For decades, Philadelphia's Cosa Nostra had been conspicuously low key. Philadelphia magazine called the organization headed by Angelo Bruno "the nicest family." Bruno, unlike gang leaders elsewhere, lived modestly and there was little violence in his family. That ended when he was murdered in 1980.

A new generation of Mafios had taken him out and replaced him with men exactly the opposite. In just a few years, there were 17 murders associated with the leadership of Nicky Scarfo, whose small size led to the nickname "Little Nicky." Most of the victims were fellow mobsters. Scarfo would kill on a whim. He seemed to take pride in his ruthlessness. When Doug Haas heard Scarfo's name associated with Fort Lauderdale, he knew big trouble could be coming.

Scarfo was expansion-minded. He had taken his Philadelphia organization to Atlantic City when gambling was approved. Through strong arm tactics, including killings, he worked his way into various businesses, including casino ownership. He imposed a tax on anyone who had a business his organization could influence. That history suggested his move to Florida would break the long-standing open territory tradition, and that would lead to mob warfare. It was a situation made to order for MIU.

Although the Pennsylvania source knew Scarfo was becoming active in Fort Lauderdale, he had no further information, including where he was living. There was no record of his name on any real estate. Haas, through an Atlantic City connection, discovered that Scarfo had a house in Coral Ridge listed in a local businessman's name, and it was already a hotbed of Mafia activity. Thus began a surveillance that has gone down as an historic intelligence coup.

MIU rented a unit in a condominium across the canal from Scarfo's house. For almost two years it had a birds eye view of constant mob activity, whose openness amazed both local and out of state authorities, including the FBI, who had a squad assigned to the investigation. Scarfo assumed he was free from the scrutiny he experienced in the north.

In fact, every move he made, along with numerous associates, was closely followed. Haas was quoted in a 1990 piece we wrote for the Sun Sentinel's Sunday magazine, Sunshine. It was rare publicity for the secretive MIU.

"At times we had so many people on the case that Scarfo's car was the only car on the road that wasn't one of ours," says Haas. "We had cars behind him, in front of him and beside him. We were the traffic."

Chuck Drago, the lead detective of some 20 MIU agents assigned to the case, was in the same 1990 article.

"One time Scarfo had 29 people at the house for a party," Drago recalls. "They were all men, all documented mobsters. And they did things they would never do up north. For instance, we got pictures of them lining up to kiss Nicky. Usually they do those rituals in the clubs where they meet. But they did this right out on his patio. You had to kiss Nicky, because you were in deep s--- if you didn't."

Drago actually sat beside Scarfo's breakfast table at a oceanfront hotel and heard him plan to knock off one of his supposed Mafia rivals.

MIU supplied Pennsylvania authorities with that dramatic information, along with numerous photos and tape recordings, for Scarfo's eventual trial. The evidence was so compelling that several of his mob flipped and testified against their leader. Drago was one of several MIU agents who were star witnesses at the trial. The trial was one reason MIU got so little ink. It was held in Philadelphia, and Scarfo and 16 mob associates were convicted. It represented the heart of the Philadelphia/South Jersey mob, dismantling an entire organization in a way unmatched by anything before or since.

Nicky Scarfo, sentenced to life, died in prison in 2017. By then Doug Haas, who rose from sergeant to captain during his MIU service, was long retired from the Fort Lauderdale PD, and had worked a few years heading organized crime units for the Broward Sheriff and State Attorney's office. He now lives in New Hampshire where he continues a 20-year career as a private investigator.

MIU was always tricky to hold together with different entities and their changing leadership. It was dissolved when Ken Jenne became Broward County Sheriff in the mid-90s.

This memoir is occasioned by a visit recently from Doug Haas. He reminisced with understandable pride about the MIU era 35 years ago, especially the Scarfo investigation.

"It's the only time an entire organized crime family went down," says Haas. "MIU got them before they could become entrenched down here. And if it hadn't happened, it would have been a blood bath."

This may be a little late for full effect, but considering that only two percent of the U.S. population has been vaccinated, it may save some people valuable time. We got our second dose of the vaccine (the Pfizer variety) at exactly the same place and almost the same time as our first. But it took four hours less.

Even with vaccination outlets increasing rapidly, there will likely be long lines as younger people become qualified for their shots. We therefore draw upon our recent experience to offer some insider advice as to how to jump the line. It is: don't get in line, at least not at the same time everybody else shows up. Be patient. Don't show up early.

Getting ready for our second dose recently, we heard from a neighbor that the worst time to show up was first thing in the morning. He said people figured the earlier they checked in, the faster the service. The result was lines starting to form an hour or more before sites open. The result was usually a longer wait than if people came later in the day when the morning rush subsided.

We decided to check this out. The day before our second dose, we showed up at our site - Fort Lauderdale's Central Broward Park on Sunrise Blvd. near the Swap Shot, a little after 8 a.m. It had just opened and the line to enter the park was more than five blocks on Sunrise Blvd. and then turned north on 31st Ave. God only knows how far north it extended. Based on our first experience, we figured it would take at least an hour to even enter the park and join the serpentine line crawling to the vaccination tents on the other side of the park.

We came back around noon and noted that the line, while still backed up on Sunrise Blvd. was only about a block long. We wondered what it might look like in another hour or so. Anyway, our decision was made to show up about 12:30 p.m. We quickly realized we were right. There was no line on Sunrise Blvd. and the column in the park was notably shorter than it had been three weeks earlier. Furthermore, relatively few cars arrived soon behind us. On our first dose, dozens of cars came in right after us.

Good fortune bred good fortune. It was clear the line was not only shorter, it was moving much faster. On our first visit, delays between cars moving were often several minutes; drivers were shutting down engines during long pauses. People left their standing vehicles to make quick trips to the portapottys along the route. This time the stops were much briefer. The whole operation was improved. Kids checked to make sure everybody in line was scheduled for that date, and that everybody was over 65. But when we reached the end of the line, the big reason was apparent. We had not counted the tents administering the vaccine on our first visit, but this time there were obviously more. We counted 11.

The bottom line. We were in and out in just over an hour and a half. The first visit took five hours. Going late might not be as effective as younger people sign up. Our group was largely retirees who could make their hours. Working people might not have such flexibility.

For some, going early may be the only option.

But for many, we are confident the last will be fastest.

Larry King. It was a name we heard in 1970 a few times before we left Philadelphia. People who knew South Florida said he was a media celebrity we should get to know. He was a radio star, something that did not exist in Philadelphia, where only TV personalities rated top billing. It took some time, but we did get to meet Larry King. Frankly, we had not been listening to his radio work. He was identified with Miami, and our magazine's circulation was Fort Lauderdale and north.

That changed, however, in late 1971 when we had a chance to acquire Miami Magazine for a song. That book was barely alive, and the chap who ran it suggested we meet Larry King, who might prove useful. King had just made news by being fired from his broadcasting jobs after he was arrested, accused of stealing money from an influential friend. The situation was blurry at the time, but it related to large gambling debts King had incurred and using money intended for other purposes to handle that debt. He needed work, and we met at lunch to discuss it.

We had no money to pay him, but that did not seem to matter. He wanted exposure to keep his name alive. We recall that for a man possibly facing jail time, he seemed relaxed. You had to like him. He may have actually written a piece for our new magazine. Copies of that early issue do not exist, but we recall reading a chatty, inoffensive column that he submitted. If we did use it, he is a member of an elite club - men who wrote for obscure Miami Magazine before they became national figures. The other man was Bill O'Reilly.

It appeared Larry King was finished, but over the next few years, we were vaguely aware that he was still around. His legal problems were settled, and he was back on radio and doing writing for local publications. But it was not until the mid-80s when he began appearing on national TV for Ted Turner's rising CNN cable station, that we realized the extent of his recovery. It seemed overnight that his interviewing skills had translated perfectly to live television, complete with his memorable suspenders and hunched forward on-air posture. He had risen from near obscurity to become the number one attraction on cable and a national figure.

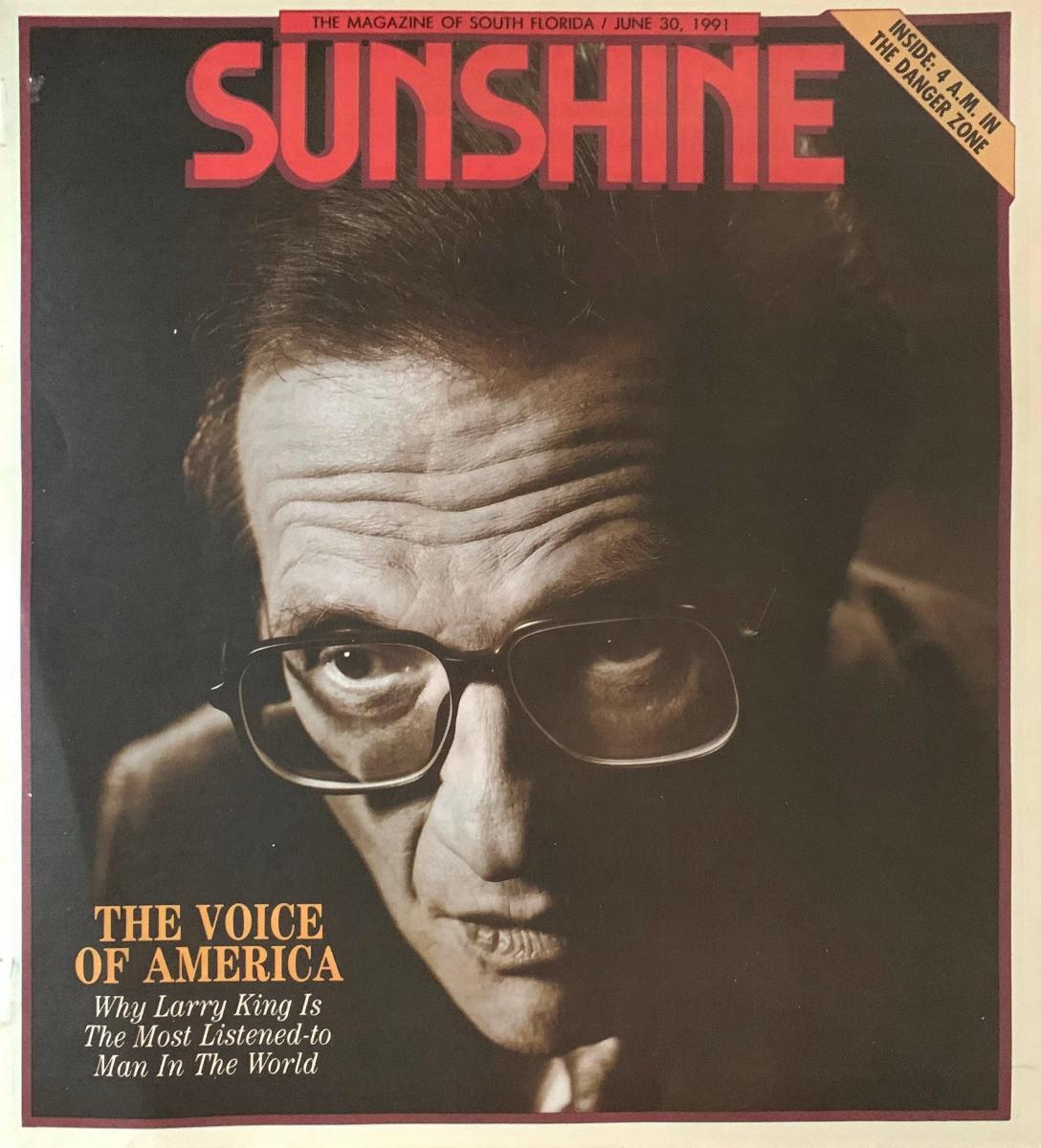

Our own fortunes had taken a nose dive. A reorganization effort in 1982 resulted in a 10-year lawsuit over control of the magazine. During that time, we freelanced for anybody whose check would clear. Much of the work was for Sunshine, the Sunday magazine then published by the Sun Sentinel. By the spring of 1991, as King's popularity continued to grow, along with the years since he left Miami, we figured many of South Florida's new residents might not know of his tangled broadcasting roots here. We also figured it would be an easy story to do.

It was. We arranged to sit in on his nightly Washington-based one hour TV show, followed by several more hours of radio work at the Mutual Broadcasting station just across the Potomac River. It was sort of a "day in the life of" story, and Larry King made it easy. We met about an hour before his 9 p.m. television show and chatted as he went through make-up and prepared for upcoming interviews. His principal guest that night was reporter Bob Woodward of Watergate fame. He was promoting a new book and was not at the CNN studio behind Union Station. "Nice to do another book with you" was the first thing Woodward said when he appeared on the remote TV screen.

King had not read the book. He never did, preferring to let the author tell what it was about. There was little remarkable about his quotes in our story, at least not today. In fact the wording of some of his recent obituaries in the national press was so similar to stuff in our piece that we wonder if it was not part of files news organizations accumulate for death watches. Anyway, the Woodward interview went smoothly and as usual, King made his subject look good, with interesting but non-confrontational questions. He was criticized for asking mostly softball questions, but it was that quality that made figures as important as U.S. presidents want to appear with him.

"I've always considered myself a conduit," he expained while driving to his radio site. "I leave myself out of it. I never use the word I. I ask the beat questions I can, and I let the viewers ask their questions."

Larry King, having interviewed so many people on so many subjects, literally interviewed himself, answering questions he had not yet been asked. He exuded confidence and candor. He did not know who that night's radio guests would be and wasn't worried about it. His range was so broad that a mere hint of a topic would quickly be enough for him to wing it.

He showed that late in his three-hour radio gig, which consisted of several interviews and numerous phone calls. King loved sports (he was on the Dolphins originally broadcast team) and between breaks that night was checking baseball scores. It was apparent that his gambling habit was still alive, but now he could afford it. At one point he asked where we had gone to school, and the word "La Salle" was barely out of our mouth when he exclaimed, "I can see Tom Gola now in the Garden. What a ball player! LaSalle had sleeves on their uniform."

This was 40 years after Gola's college days. He was player of the year and led La Salle to the NCAA championship, but after four decades, outside of Philadelphia his name had begun to fade. But King not only recalled him instantly, he added that trivia about the classy uniforms. You got the impression he could easily go on for an hour recalling teams that played in Madison Square Garden and the uniforms they wore.

Asked about his comeback from the dark days in Miami, King said: "Did I foresee all this? Jesus Christ, no. I always knew I'd come back. But national? Never." Later he discussed his income, about $2 miilion a year from TV, radio and books he wrote. "I really started making major money at 55. That's not young to start making money. It's kind of a hoot."

He shared that hoot as a unique broadcasting figure for the next 20 years.