Coverage of Broward Crossing in Sun Sentinel's January 14, 2022 edition

Our recent blog on the wall-to-wall development being permitted in downtown Fort Lauderdale appeared a day too soon. Almost on cue, the Sun Sentinel reported on a proposal for the tallest condominium in the city, located just west of the Brightline station on Broward Boulevard. The novel modern design would provide for 1,000 new units.

In describing the 47-story structure, to be known as Broward Crossing, the paper illustrated the divide between the city officials' attitude toward growth, and the thinking of people who have to deal with the consequences of the seemingly endless parade of cranes signaling tall new buildings. Nobody questions the location. It is within a short walk of the commuter train.

"It's very dramatic," Mayor Dean Trantalis said. "It's dramatic in form and shape as opposed to a static rendering that we see in almost all the other buildings in our downtown. It creates movement and awe as you look at it."

Commissioner Steve Glassman, who represents the district where the building would rise, also sounded enthusiastic. "My first impression was ‘Wow,’" Glassman is quoted. "I thought the architecture was really cool. We have several cool buildings downtown, but we have too many boxes. This design really does make a statement for Broward Boulevard as a gateway for people heading into the city from the west."

Charlie Ladd, a developer and board member of the Downtown Development Authority, thought the design's flair would inspire other developers to be more creative in their designs. But none of those individuals mentioned the impact of all those new units on those of us already living here. To the contrary, some of their quotes sounded as if they were written by the developer's PR firm.

Christian Garay, president of the Sailboat Bend Civic Association, praised the design and added that he has friends in real estate who tell him the city needs more high-rise towers. "Now more than ever you're seeing a lack of available properties out there, both commercial and residential," he said. "There's not enough properties on the market to keep up with demand. The city needs to progress. And buildings like this show progress.”

Charlie Ladd concurred, and responded to people who said the new building was just too much. His comment: "Last I heard they don't have cities in the United States where they say, ‘No one else can come here.’ Builders will stop building when people stop filling up the buildings."

He said current high rises are full and the city needs to facilitate new development. The comment seems doubtful to anyone who has seen buildings at night with few lights on suggesting occupancy.

As far as cities that don’t welcome newcomers, you don’t have to go very far to find Florida communities which don’t want many newcomers. Stuart and Vero Beach, for instance, in the 1970s passed height limitations (about four stories) to prevent what they saw going on to the south. And this was before Fort Lauderdale’s downtown took off. Fort Lauderdale’s one tall building was nine floors. It was rather a reaction to wall-to-wall high rises along the beaches of Dade and Broward counties.

Fort Lauderdale was — and still is — used as an example of what these cities don’t want to become. And it is no coincidence that both Vero and Stuart are filled with people who fled South Florida to return to an unhurried lifestyle that attracted them in the first place.

The irony of the opposition to the proposed latest big building is that the site just west of the railroad could use development. It is a perfect location for a nice four-story office building which would attract commuters using the convenience of Brightline from up and down the coast, and be gone after work, rather than new residents who would rarely use the train but add their cars to the worsening traffic mess.

The Sun Sentinel recently had several editorials regarding the seemingly unbridled growth being permitted in downtown Fort Lauderdale. One piece dealt with the proposal to put condos in Bahia Mar. The paper urged the city commission to be careful about approving any plan that hurts the annual boat show, and isn't the best deal for taxpayers. Another story dealt with a proposal to build a condo along the New River that is opposed by residents as too tall for its location among much smaller buildings. The idea even has opposition from the Rio Vista neighborhood on the other side of the river. Residents think a trend toward tall buildings so close affects their own low rise quality of life.

The feeling here is the city should approve all new buildings, no matter how tall or ugly, as long as the people who buy in those buildings are not permitted to drive cars. It seems that in approving so much tall construction over the last decade, the city ignores the traffic they generate that compromises the quality of life of the older, increasingly attractive neighborhoods on the edge of downtown.

In one of its pieces, the paper asked the question that residents have been asking with each new skyscraper: Why do people who almost always run on controlled growth platforms readily approve exactly the opposite when they take office? Developers always say how their projects enhance their neighborhoods by bringing in new business and taxpayers. They never mention the negatives, which include the possibility that access to their buildings could be underwater in a few years, to say nothing of the traffic messes they create.

The latter gridlock is already bad, and will only get worse when (and if) all that new construction is occupied. There are complaints all over Broward County, but the worst problem seems to be getting people from downtown to the beach. The most used route is the biggest problem. Most traffic between the beach, downtown, and western Broward is on Broward Boulevard, which links to Las Olas Boulevard and then on to the heart of beach activity. The problem is that link.

Broward and Las Olas are both four lanes, but Broward ends at Victoria Park. The only way to Las Olas is three blocks of narrow, two-lane residential streets through the old neighborhood called Colee Hammock. The city over the years has made 15th Avenue the primary connection, and it simply can't handle the increasing volume of traffic. During busy hours, vehicles line up for blocks on Broward and Las Olas as drivers wait to make the turn onto 15th. As a result, impatient drivers cut through other streets, some of which are notable for their abundant heritage oaks and well-preserved older homes, and are favored by people walking dogs and pushing baby carriages.

The only solution advanced recently is the exotic Elon Musk tunnel from the Brightline Station on Broward all the way to the beach. But because its two lanes will only accommodate special vehicles and not ordinary traffic, it will not come close to solving the problem. Commuters still need their cars at either end of the tunnel. The only people who would use it are tourists who don't need cars, and they aren't the cause of gridlock.

The impractical tunnel idea, however, leads to a more practical one. Why not a real tunnel, such as the Henry Kinney Tunnel under the New River? It need not be an enormously expensive tunnel all the way from the Brightline location to the beach. It could be just long enough to connect Broward Blvd. to Las Olas, following the present traffic jam corridor from 15th and Broward over to Las Olas and then a few blocks toward the beach, coming up where the Las Olas Isles begin. It would be a challenge to build it along Broward, but no more so than it was to build the entrances to the New River Tunnel on U.S. 1 years ago. The access on Las Olas would be easier as there is a median which provides plenty of room.

Now that would solve the problem, at least as it exists today. In the long run, if all the tall new buildings under construction are ever filled with office workers and residents, it is hard to imagine any solution to the avalanche of traffic that will follow. Perhaps city planners and commissioners will give that prospect some thought the next time they are asked to approve buildings that are simply too big for this city.

It was the summer of 1996 and Senator Bob Dole was running for president. Some thought he was not a strong candidate, despite his well-known war record and years of experience in Washington, because he was not a show horse and not as known to the public as some other senior senators. I was inclined to make him the second Republican I voted for for president (there was also one independent). His opponent was incumbent President Bill Clinton, who always rubbed me the wrong way. I had chuckled in approval when, following the 1996 election, ABC's David Brinkley said that Clinton "has not a creative bone in his body."

And so it came to pass that candidate Dole came to Fort Lauderdale for a reception sponsored by the Republican Party. It was at a beach hotel, and Mark McCormick, somewhat active in the party at the time, was invited, and he brought along his dad. We arrived a bit early and were surprised to find Senator Dole almost alone. What was immediately apparent was his handicap from his WWII wound in Italy. He quickly extended his left hand to shake, while his right hung uselessly by his side.

He must have asked Mark what he did, and Mark said he was just finishing six years in the Navy. Dole asked about his service, and they chatted for several minutes about Mark having been navigator of a fast frigate, and then teaching at the Navy Surface War School in Newport, R.I. The room was filling quickly, and as others approached him, Dole continued to show interest in Mark's background. Soon he turned to the work of the night and there followed two hours of greeting strangers and listening to speeches. By the end of the night he must have met hundreds, maybe a thousand people, most of whom were strangers.

We did not plan it that way, but as we headed for the door we chanced to see Dole again. This time he was surrounded by people, but to our amazement, he noticed Mark and made another comment about his Navy time. I have met a lot of politicians over the years, and even though some of them are good at names, we doubt many of them meeting so many people at a reception would remember someone five minutes later, much less resume a conversation from several hours before. Needless to say, he got our votes.

It wasn't enough, but as was apparent in the memorial service for him Thursday, Bob Dole has gone down as an all-round patriot, an admired war veteran, a legislator known for his integrity who got along and was respected by people on both sides of the aisle, and a man who put service above self.

One could not help but contrast this dominant Republican from what seems a distant era with the dominant Republican today — the latter a draft dodger who doesn't begin to know the meaning of integrity, who seems more at home with our nation's enemies than his own people, and who places himself above all others, living and dead. And despite his glaring abuses, continues to enjoy the support of many members of his own Republican party who are as dishonest as he, or too gutless to disown him.

Photo Credit: President's Commission on Care for American's Returning Wounded Warriors (PCCWW), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

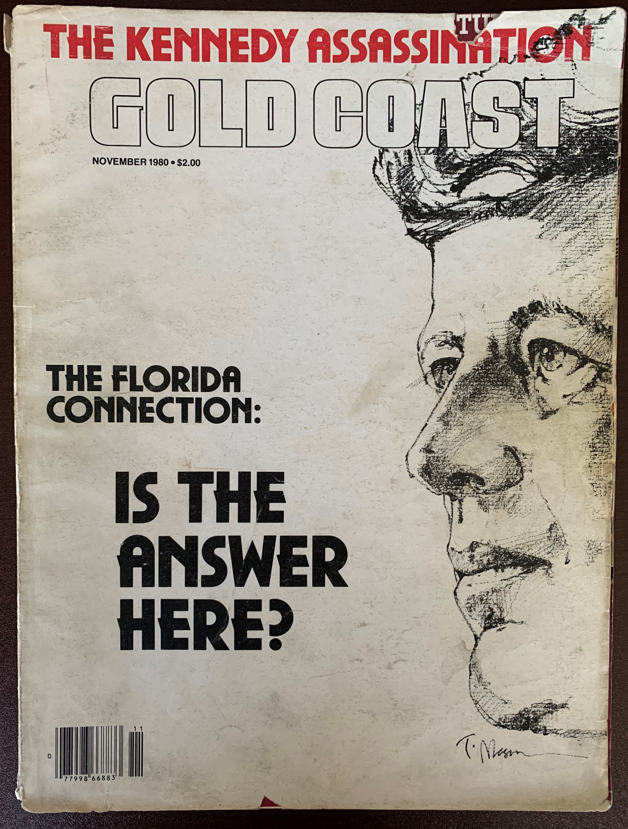

Gaeton Fonzi's first piece on the JFK assassination appeared in the November 1980 issue of Gold Coast.

"Don't you see it, boys? Don't you see it? There's only one outfit who could have pulled this off."

It has been 56 years, but you can still hear the gravelly voice of Vince Salandria in a motel room in Wildwood, New Jersey, telling Gaeton Fonzi and me that he was convinced the CIA had murdered President John F. Kennedy. The Warren Commission had been recently released, assuring us that Lee Harvey Oswald was a lone assassin. The report had been widely praised, but the problem was that those who praised it hadn't read it. They had just seen a summary. Almost nobody had taken the time to examine the 26 volumes of evidence supporting its conclusion.

Vince Salandria, a Philadelphia school board lawyer, had read the full report, and over the course of an hour he had pointed out the glaring inconsistencies which made it obvious that more than one shooter had been at work that day in Dallas. Salandria, a chronic mistruster of government, had sensed a CIA hit, especially when Oswald was crudely eliminated in a police station after proclaiming his innocence. This was long before researchers had found evidence that Oswald was an intelligence operative who had been set up to take the blame for the murder. The CIA connection has come out in bits and pieces over the decades — most recently last week — more on that later. And one of those researchers, and the man who uncovered the most damning connection to the CIA, was Gaeton Fonzi. He wrote some of the first articles challenging the Warren report for Philadelphia magazine.

He was no ordinary critic. Pennsylvania Senator Richard Schweiker, who recalled his stories in Philadelphia, hired him when he headed one of the committees that reopened the JFK probe in the mid-1970s. Schweiker shared Vince Salandria's view, describing Oswald as having "the fingerprints of intelligence all over him." He wanted Fonzi to look into the CIA's relationship to the anti-Castro movement in Florida and Oswald’s connections to that group.

Over several years Fonzi had access to government information that no other researchers enjoyed. It eventually led him to Antonio Veciana, who headed Alpha 66 — the most active Cuban American group trying to kill Castro. Before Veciana even learned what Fonzi's real mission was, he made the startling revelation that he had seen Oswald in the company of his CIA handler, a man who had risen to one of the high ranking jobs in the agency, shortly before the November 1963 hit on Kennedy.

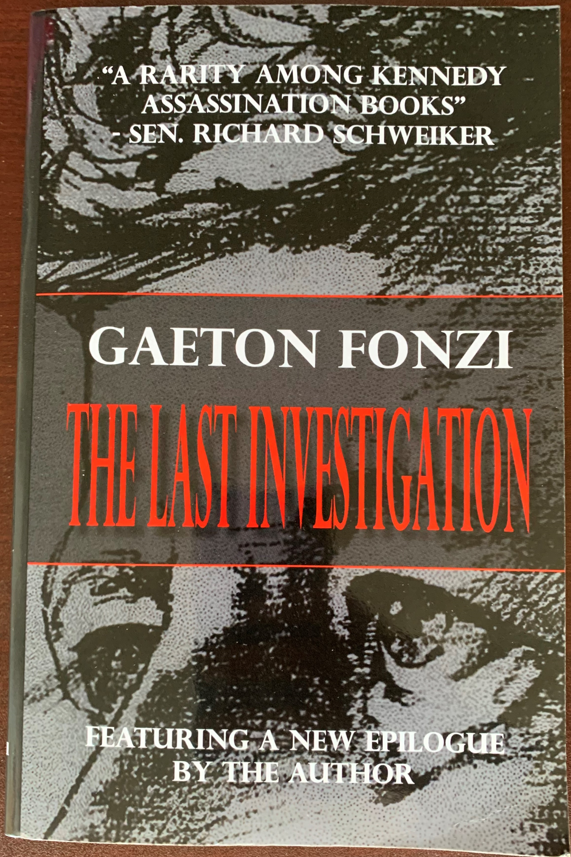

Fonzi's 1993 book, The Last Investigation

Fonzi's magazine pieces ran over three issues in Gold Coast in 1980, and after considerable additional research, appeared in book form in 1993. The Last Investigation has undergone two reprints. In its 443 pages of text and nine pages of fine print footnotes, Fonzi revealed how the CIA operatives, both Cuban and American, sabotaged his work with false leads which wasted his time. Political figures friendly to the agency also impeded his committee's work, especially when it attempted to get cooperation from the CIA, and ultimately shut it down for lack of funding. But Fonzi realized that his anti-Castro contacts seemed to know stuff about Oswald and the assassination that they only hinted about. And most approved of Kennedy's murder as just retribution for his not using our military to save the disastrous 1961 Bay of Pigs invasion. Despite these obstacles, the committee’s final report, which was largely written by Fonzi, concluded that Kennedy’s death was not the work of a lone gunman, but a conspiracy. By whom was not included.

Which brings us to two weeks ago when the Miami Herald ran a story about Ricardo Morales, one of Veciana's allies in the Alpha 66 organization. He was mentioned in Fonzi's book. Morales’ son said his father told him and his brother late in his life that Oswald was one of the men he gave rifle sniper training to for the CIA. He did not think Oswald killed President Kennedy. He also said that two days before the assassination, his CIA handler sent him to Dallas to await a mission, and brought him back after the assassination. He thought he was part of a "clean-up" team in case they were needed. They were not. He also said he feared for his life because he knew too much about the CIA nefarious activities. That statement echoed what Veciana told Gaeton Fonzi in the 1970s when asked why he kept his explosive information quiet for more than 10 years. He said his goal was to eliminate Castro and did not want to alienate his CIA supporters. Also, he said if they murdered the President of the United States, why would they hesitate to silence him?

Ricardo Morales’ story would not have surprised Fonzi, who died in 2012. His book mentions others who told similar stories about going to Dallas for a mission they were never asked to perform.

The same Herald piece noted that President Biden recently joined a series of presidents to postpone declassifying the remaining 15,000 pages of documents pertaining to the assassination. According to the Herald, the stated reason: The need to protect "against identifiable harm to the military defense, intelligence operations, law enforcement, or the conduct of foreign relations that is of such gravity that it outweighs the public interest in immediate disclosure."

Isn't that some statement? Fifty-eight years after a president is murdered, revealing all the government knows about it will endanger national interests. That admission is that some government force that existed in 1963 is still operating. Those few — those dwindling few who have followed this case from the beginning — think that at the very least those documents will show Oswald's connection to the CIA and suggest decades of efforts by our government to conceal the fact that its lesser angels murdered a president.

Don't you see it, boys, don't you see it?

The Boring Company

The idea of a tunnel from downtown Fort Lauderdale to the beach, under Las Olas Boulevard, has been proposed to solve the rush hour gridlock on the few roads to the beach from the heart of the city. That would be Las Olas Boulevard, and the narrow north-south streets connecting to Broward Boulevard.

Las Olas, east of 15th Avenue, is wide enough to handle heavy traffic with its four lanes. But what is not wide enough are the few streets connecting that boulevard to the similarly wide routes headed in every direction from downtown. The biggest jam is on 15th Avenue, between Las Olas and Broward Boulevard. You have busy four-lane commercial boulevards being linked by two-lane, largely residential streets. That is a formula for traffic jams. There are days when traffic waiting to be funneled into the narrow corridor backs up for blocks west on Broward.

The situation has been building for years, but it has worsened with recent efforts by Las Olas business interests to discourage heavy commuter traffic along its section of shops and restaurants. That has put more pressure on the streets of Colee Hammock, as frustrated motorists look for short cuts through the attractive neighborhood of oak-lined streets east of the downtown business district.

The tunnel would seem to be a solution to the problem. If it works. And that is a concern as momentum for a revolutionary concept seems to be gaining speed fast.

What is being proposed by Elon Musk's Boring Company is not a tunnel in the conventional sense — not like a tunnel under the Hudson River to New York or, more locally, the Henry Kinney Tunnel under the New River in Fort Lauderdale. As presented so far, details of the tunnel remain vague, but it appears to be a modern version of a subway, used only by Tesla vehicles. It would run from the Brightline Station on Broward Boulevard at the FEC rail crossing to the end of Las Olas on the beach, with a few stops in between. But you can't drive your own car through it. And that makes one wonder how useful it would be. How much of the traffic now using Las Olas and cross connecting streets requires people to have their own vehicles? Last week a source in Fort Lauderdale's communications department said there have been no studies of traffic patterns for the affected areas. That would seem to be a necessary first step in determining whether this tunnel would serve anybody but tourists going to and from the beach from downtown hotels.

As one who lives in Colee Hammock and sees the traffic movement daily, it seems most of the traffic through the neighborhood are cars that people need for daily commutes. They are either people who live on the beach or the Las Olas Isles and head to work outside the downtown, or vice versa. Most traffic seems to cut over from Las Olas and turn west on Broward to Federal Highway or other north and south routes. What good would a tunnel do them if they still need their cars to complete their commutes after they leave the tunnel. Some people would find the tunnel convenient to take them to the Brightline Station, where they catch that fast train either to Miami or West Palm Beach, but that is not a large number. And obviously tourists in downtown hotels would appreciate a quick way to the beach. But who else would use it?

A real tunnel that could handle conventional traffic would undoubtedly relieve much of the congestion. Before it gets swept up in the euphoria of an exotic concept, the city should first figure out where people in the affected area are actually going. That would help predict if the proposed tunnel might turn out to be a novel ride for tourists, but all-but-useless for locals fighting gridlock.

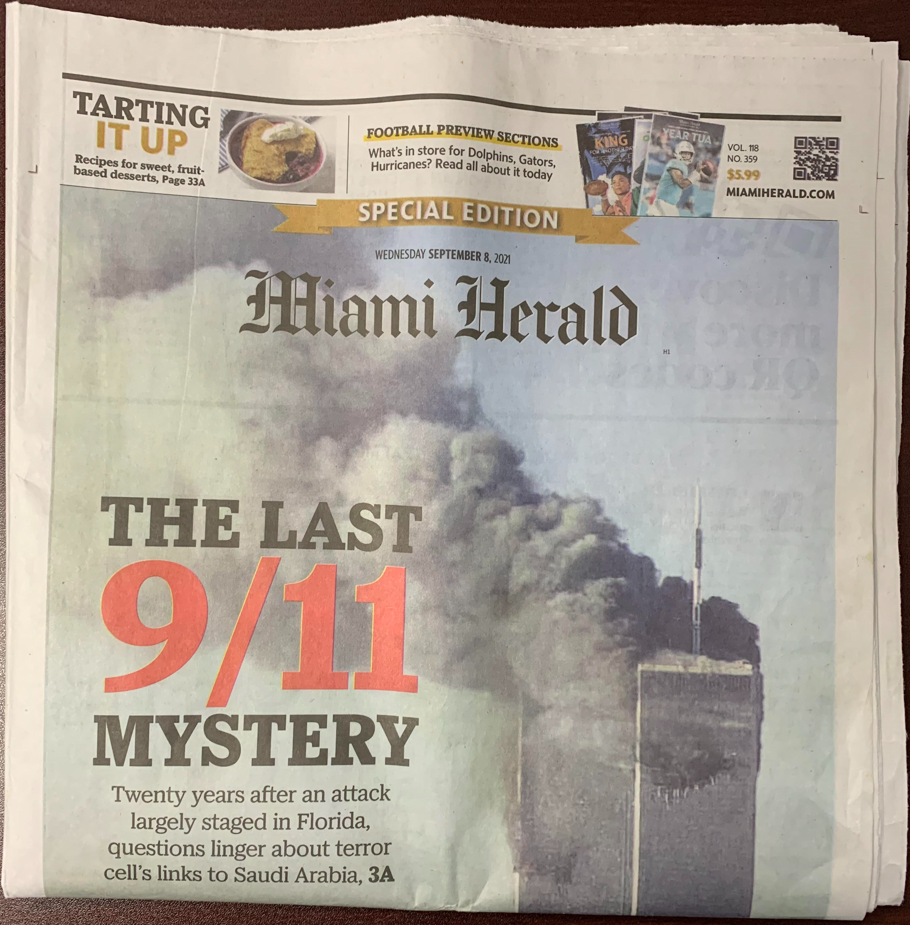

The front page of Miami Herald's September 8, 2021 edition

This piece has been held for several weeks, waiting to see if a dramatic Miami Herald story about 9/11 got picked up around the country. As of this writing, only the Tampa Bay Times and the Bradenton Herald have run it. There was also an excellent story about the background of the Herald report in the recent issue of Sarasota Magazine.

Watching the exhaustive coverage of the 9/11 anniversary and the country's chaotic departure from Afghanistan, one would get the impression that the whole matter began and ended in Afghanistan. Very little mention was given to the fact that 14 of the 19 suicide hijackers were from Saudi Arabia.

An impressive and dramatic exception to this omission was the Sept. 8 issue of the Miami Herald. In a special edition, the Herald devoted its entire front page, with a full page photo, and four more full pages and part of a fifth to a story revealing connections in Florida between the hijackers and people associated with the Saudi Arabian government. It also described two decades of the FBI elaborately trying to cover up the facts. Rarely does the Herald — which, despite mounting financial pressures, is still among the most highly regarded papers in the country — devoted so much space and resources (three writers contributed) to a story that, by its own admission, it did not originate.

The paper did credit the originator: Dan Christensen, and his online investigative site Florida Bulldog. Christensen, the paper noted, has been on this story for more than 10 years, slowly prying loose details of the mystery from a reluctant FBI. Christensen, based in Fort Lauderdale, started his organization when he took a buyout when the Herald first began cutting back its staff in 2009. Over the years, he has gotten an occasional reference in stories questioning the role of the Saudi government in 9/11, but this is the first time he got the serious credit he deserves. Florida Bulldog has published numerous investigations, but none with the international impact of this one. Make that potential international impact, for Christensen's stories, especially this one, have never received the attention they seem to warrant.

The details of this tale almost require a mystery story buff to grasp it all. It has taken Christensen a decade to research, and the Herald a lot of space to explain. Christensen and Bob Graham, the former Florida Governor and U.S. Senator who chaired the Senate Intelligence Committee during 9/11, were tipped in 2011 by another investigative reporter, Irishman Tony Summers, about connections between suspected Saudi government operatives and the hijackers in Florida. Summers is a familiar name. He also worked with our former Gold Coast Magazine colleague, Gaeton Fonzi, in his landmark work on the CIA's suspected involvement in the Kennedy assassination.

Summers had picked up information from sources at a Sarasota community who became suspicious of the behavior of a Saudi Arabian family. Following up, Christensen discovered that the leader of the hijackers visited the family, who had connections to the Saudi government. Most of the hijackers spent time training and even partying in Florida before the event. They seemed to have mysterious financial support and assistance, but from whom? The Sarasota family was well off. They lived in a gated community, which they left for Saudi Arabia shortly before 9/11.The departure was so hurried that they left their cars and other valuable items behind, even dirty diapers. That was what attracted the attention of neighbors and the community's security unit.

Christensen also uncovered similar connections in Southern California between hijackers and individuals associated with the Saudi government.

Christensen's original article, and subsequent pieces, have been picked up by the Herald. He shared his findings with Graham, who had suspected a Saudi Arabian government connection to 9/11 but had no proof. Graham, 84 and retired from public life, has not commented recently, but he has gone on record accusing the FBI of withholding crucial information, including the Sarasota connection, from his commission. In fact, there was no mention of the Sarasota family in the FBI's original report. It wasn't until Christensen filed lawsuits that the FBI revealed it had investigated the Sarasota family connection and found numerous contacts with the hijackers, but did not establish a connection to the 9/11 attack. Confronted by that blatant contradiction, the FBI later said the agent who filed the report did a sloppy job, suggesting he did not know what he was doing. Lawsuits have since forced more documents to become public, including one that indicated the FBI was still looking at the Sarasota connection 10 years after 9/11. Bizarre, to put it mildly.

These lawsuits were filed pro bono by Miami attorney Tom Julin, who specializes in first amendment cases. He has gradually forced release of some of the abundant classified records on 9/11. Christensen, and presumably the Herald, continue to press the case. "There is so much more," Christensen told the Herald. "All of us want to know what happened.The FBI is hiding that from us, and I don't think they have the authority to do that."

Except for the Tampa Bay Times and the McClatchy-owned Miami Herald and Bradenton Herald, Christensen's work has been ignored by the state's newspapers. One especially wonders why the Sun Sentinel has not mentioned this important story developing for years under its nose. Its editors know Christensen well. His wife Doreen worked for the paper for years. It would seem smart journalism to at least acknowledge such a story. His work has had one interesting result: It has bolstered the case of thousands of families of 9/11 victims who are suing in federal court the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and related entities.

Broward County recently lost two important and popular figures who, although in very different fields, have had a memorable impact on our lives. Civic and political leader Joel Gustafson and public relations agent extraordinaire and Fort Lauderdale booster Jack Drury passed away in the last weeks. Gustafson died on August 31 at age 83, Drury on September 11 at 90.

The men shared an interesting dynamic. Gustafson’s career was often political but he had an excellent PR sense, and was very popular with the media. Drury, although in PR, not surprisingly had good political instincts. Almost everybody liked him, and if he did not fancy people he worked with, he kept it to himself, at least until they belonged to the ages.

In both cases there was no public notice for days after their deaths, a revealing comment on these unusual times.

Jack Drury (screenshot: sun-sentinel.com)

Jack Drury came to Fort Lauderdale in 1960. He was from North Jersey and had majored in marketing at Seton Hall. He had begun his PR work for a New York firm that transferred him to Fort Lauderdale to handle the big Gill Hotel account. He struck out on his own two years later. He was well on his way when I met him in 1971.

He was one of the first important contacts I had when arriving in Fort Lauderdale, and goes down in our personal history as one of the handful of people who conspicuously helped our restyled Gold Coast Magazine gain acceptance under difficult circumstances. He is in good company. Two of the others were Theresa Castro and Joe Amaturo.

I knew almost no one in Broward County when we bought Gold Coast Magazine. Not without cause, the woman who sold it hated me and my partners. She thought she had sold to a local wheeler-dealer who would be a sugar daddy, leaving the book-running to her. She had not expected real magazine writers from the highly respected Philadelphia magazine to be involved. I soon learned she was trying to sabotage our efforts to improve the publication, which started out with the name Pictorial Life and was amateurish, but financially successful.

Jack Drury contacted the magazine in regard to the 15th anniversary of the Mai-Kai restaurant in 1971. Drury introduced Bob Thornton, one of the brothers who owned what at the time was likely the city’s best-known restaurant. I was impressed by both the handsome and engaging Drury and Thornton, and the result was a readable cover story. That cover had Thornton posing beside a sexy Mai-Kai girl in a huge vat. It was a notable departure from previous covers and suggested more sophisticated directions for the magazine.

What was important about that story is that Jack Drury seemed to believe in our group and our ultimate success. Not everybody did. And over the years, he involved our magazines in almost everything he promoted locally. Of course it was smart business for him, but it was also a standing endorsement of our product, and much appreciated.

In the ’70s, Drury was at the height of his professional success. He had represented, or associated closely with, some very big names. He could write a book about it; in fact, he did in 2008, in paperback form. Fort Lauderdale: Playground of the Stars featured photos and commentary on the many celebrities he had worked with. He was especially close to Johnny Carson and sidekick Ed McMahon, but the book also included Bob Hope, Buffalo Bob Smith (of Howdy Doody fame), Cary Grant, Billie Jean King, and many others.

It was revealing that Drury included Fort Lauderdale in the title. He was responsible for bringing big names to town. Former Fort Lauderdale Mayor Jack Seiler called him the biggest cheerleader the city ever had. In the process, he helped build events which are now strongly identified with Fort Lauderdale and South Florida.

It is often forgotten that he was one of a group that saved the Jackie Gleason Inverrary Classic golf tournament after the strong-willed Gleason, who Drury found hard to work with, decided to back off the event. They found new sponsors, and today it is the Honda Classic in Palm Beach County, one of the area’s premier sporting events. He was also active in the Winterfest Boat Parade. He brought Ed McMahon to be that event’s Grand Marshal.

In the later years of his long life, he reunited with one of his first associates in Fort Lauderdale. He had known Ken Behring since the latter began his development career by founding the city of Tamarac. Behring went on to become one of the country’s top housing builders, and eventually owned the Seattle Seahawks football team. Drury arranged for a magazine interview with the unpretentious Behring when he returned to Fort Lauderdale in connection with launching the Wheelchair Foundation, of which Drury was Southeast President from 2002 until his death. The organization has delivered more than a million wheelchairs worldwide.

A public memorial service for Drury is being planned for late October.

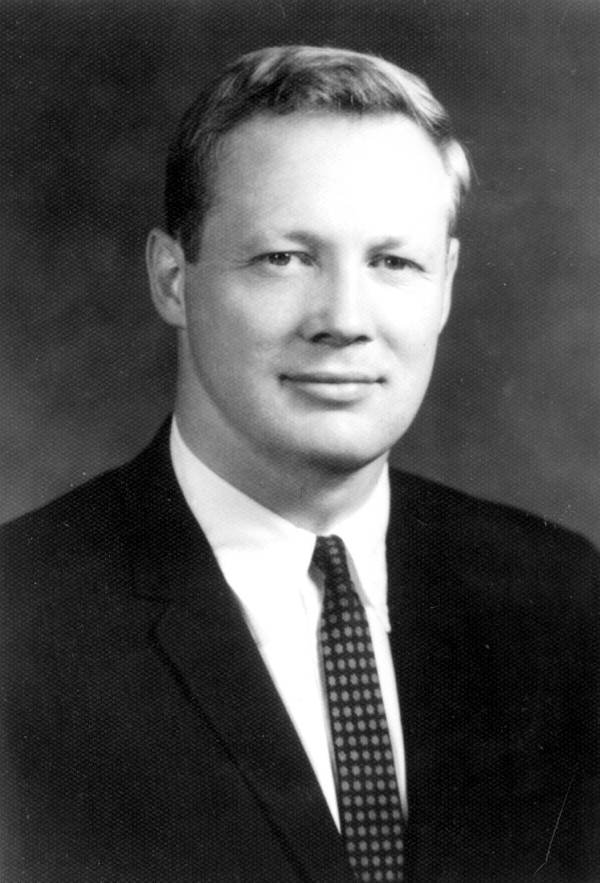

A young Joel Gustafson (photo: Florida Gov't, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

Joel Gustafson was a lifelong athlete. From Connecticut, he attended Lafayette College on a sports scholarship and was captain of both the football and track teams. He remained an active outdoorsman. He came to Fort Lauderdale after earning his degree from Tulane Law School in the early 1960s. He quickly established himself as an emerging community leader and was elected to the Florida Legislature in 1967 and served three terms. That’s where I first encountered his name when Gold Coast did a story on South Florida legislators. I was a stranger to the capitol, but Van Poole and Ed Trombetta led me to valuable contacts. In retrospect, it was a distinguished era for that body. The quality of South Florida members was especially impressive. In addition to Gustafson, they included Bob Graham, Sandy D’Alemberte, Janet Reno, and Marshall Harris, all Democrats. Gustafson, a Republican, had just departed the legislature, but his name came up often in Tallahassee, for as Republican Minority Whip he got along well with the opposite party. It resulted in some years of important modernizations of Florida’s laws.

His subsequent career filled a long obit in the Sun-Sentinel. Highlights were terms under four Florida governors on the Florida Commission on Ethics from 1978 to 2004 and six years on the board of the North Broward Hospital District. He also served on the Orange Bowl Committee, the Whitbread Race Committee, the host committee for two Super Bowls, the Breeders’ Cup, and on the boards of the Henderson Behavioral Health Center, the Broward Alliance, and the Florida Chamber of Commerce. Later in life, he was chief of staff for his longtime friend Congressman E. Clay Shaw.

In every endeavor, his charm and wit made him universally popular.

Among the many tributes to Gustafson, this one from highly respected political writer Steve Bousquet is notable:

“I knew him well, and covered him for many years as the Broward political reporter for the Miami Herald. I found him accessible, astute and candid, and someone who never took himself too seriously. I profiled him in 1991 for a story about the five most effective land use lobbyists in county government. Behind the scenes, he had a major influence in the modern development of Broward. He was in the Legislature at the dawn of what’s now regarded in hindsight as a “golden age.” Today’s Legislature sure could use someone like him.”

Amen.

Our oak tree, in the late stages of the takedown

A neighbor noticed it first. The oak tree in the back of our house had a broad upper span, as 100-year-old oaks will. Its thick branches were extending over the rear of three neighboring properties, and the neighbor to the south noticed that a large branch over their home did not look healthy. The leaves were turning brown. It was a dead limb, and with hurricane season approaching, neither of us were anxious to see it break off and land on his roof. The rest of the tree seemed to be okay, but in the few weeks that it took to get a tree expert to look at it, other upper branches were also turning brown. The dead leaves were leaving the limbs bare. At first the tree guy thought we could just cut off a few dead branches, but by the time he was able to schedule the job, the whole tree seemed to be turning brown. And huge chunks of bark were now falling off the lower parts of the huge trunk.

"Lightning hit it," the tree guy decided. "When that happens, there's no way to save it."

Now this story does not rank in gravity with the situation in Afghanistan, or even the Covid pandemic. But in our neighborhood, the death of a vintage oak tree is not a trivial matter. In fact, Colee Hammock is named for the majestic oaks which line its streets and give the neighborhood a shaded charm that has few matches anywhere in the state. That beauty was obvious to the earliest developers of Fort Lauderdale. Mary Brickell, who owned the hammock in the late 1800s, took on one of the most powerful forces in the young state to preserve it. When Henry Flagler wanted to extend the Florida East Coast from Palm Beach to Miami, he wanted to keep it on a straight line on the high ridge where Florida's watery coastal strip gives way to more solid earth. That would bring the tracks through Colee Hammock.

But Mary Brickell insisted Flagler move his route west, away from her densely wooded hammock. Thus the sharp inland veer which takes the FEC tracks west and into downtown Fort Lauderdale. She had the foresight to preserve Colee Hammock for the shaded residential neighborhood it is today. It is more than a desirable place to live. Visitors enjoy walking several streets that are largely insulated from the heavy traffic to the beach on Las Olas Blvd. It is not unusual to see people pause to photograph the more striking homes, especially those with dense moss hanging from the oaks.

Thus it was with reluctance that we had to take our ailing tree down. It was not our first oak casualty. Over 50 years we have lost three others. One, maybe 50 years old, died in the middle of our front yard several decades ago. We replaced it with a tree that has grown about half as big as the original. Hurricane Wilma cost us two trees. One, very old, snapped about 10 feet up and landed on our roof. Fortunately the leafy branches cushioned the impact and we escaped with just a few holes to patch. The other was a younger tree in the back of the house, shading our deck, that was uprooted when the top half of a very old mango tree in the adjacent yard snapped and fell on it. Many younger oaks were uprooted by that storm and were propped back up. We wish now we had done that with our tree.

Preserving the character of Colee Hammock has not been easy. Most of the houses in the 1930s and 40s were built around the position of the trees. With a few exceptions, most of the homes were modest single-story cottages, designed to the scale of their lots. Inevitably some were neglected and became knockdowns. Most new construction, invariably much larger, has been respectful of the old trees, especially those which shade the streets. Increasingly, however, buyers are knocking down the old houses, even those in good shape, simply to make room for houses of several floors which take up the entire lots. This land usury has led to the disappearance of some apparently healthy old oaks under mysterious circumstances. There is a suspicion that some trees were poisoned to justify their removal and permit much larger homes than would otherwise be possible.

John Harris, whose firm Earth Advisors in Plantation is one of the country’s leading authorities on tree preservation, understands both sides of the story. An arborist and forester who also has a master’s degree in economics, he is a consultant to environmental groups, teaches a class on the subject, and writes a technical editorial for the Society of American Foresters. He sympathizes with those who want to protect old trees, but he also understands the problems Florida governments have in granting permits for tree removal, or enforcing vague regulations to protect neighborhoods such as Colee Hammock.

“Some of the oaks may be 200 years old or older,” he says, “and as they get older just as people they have health problems.” He says an arborist supporting a tree’s removal can find numerous hazards ranging from branches extending over a neighbor’s roof to trees whose surface roots constitute a tripping hazard. He says that roots sometimes affect water pipes, and when the roots are cut back, the tree can become unstable in severe weather.

“Public safety will always win,” he adds.

Florida’s problems are compounded by a state law passed and sponsored three years ago by legislators who had concerns about mitigation on their own properties to expand homes. Says Harris: “The law is deliberately written in such generic language that is so ambiguous that it makes it difficult for any city or county to decide if they have legal standing for code violations.” The result is that some old trees are obviously removed to make room for bigger houses that are determined by local laws governing the size of a building that can be built on a lot.

Further complicating matters is that not all arborists have Harris’ integrity. One element determining a permit for tree removal is a letter of support from a certified arborist. Some Colee Hammock residents think that all some arborists need to provide such a letter is a check that clears. And in fact, when it comes to 100-year-old oaks, almost all of them could be found to have potential hazards, such as our oak, whose decayed innards could not stand Wilma's gusts. This construction trend has resulted in a number of modern "box on a box" structures which are barely separated from and in fact dominate their older neighbors. Whereas the original houses had a cozy charm, some of the new construction has all the appeal of an Army reserve center. Longtime residents are upset and bewildered by new buyers who are drawn to the neighborhood because of its attractive canopy and then build monstrous homes that remove trees and destroy the very quality that attracted them in the first place.

Our late tree, because of its location, does not change the neighborhood's leafy character. Most only knew it was taken down by seeing the remnants lying in our swale waiting for pickup. Only the backs of adjacent houses were deprived of its shade. But a few days later I awoke in the middle of the night. The bed is close to a window, and when lying down one can see some sky. And in that sky was a strange yellow oval. For a second the thought of a UFO occurred, until the realization that this object was there all along, but the thick foliage of the tree had blocked its glow.

The object is called the moon.

Photo by: DonkeyHotey, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

People may wonder how Governor Ron DeSantis can expect to be re-elected, much less run for president, after all his terrible recent publicity. The answer in a word is socialism.

Republicans all over the country, but especially in Florida, use that word at every opportunity. It works magic, particularly among those immigrants who have arrived in Florida from Cuba and other countries where their freedom has been lost. The great irony is that they have not fled socialism, although their former countries may have used that term for their political system. What these people really fled was dictatorship — authoritarianism, loss of basic rights and property, rigged elections, false imprisonment, etc. And they come to Florida and vote for people who would do the same to them if they get the chance. Go figure.

Wondering if socialism is enough to save DeSantis led to a consultation with this writer's chief Republican lobbyist, Elwood O'Goniff of McCormick, O'Goniff and Craven. He said DeSantis could survive any bad publicity by saying socialism as often as possible. The only word that could beat him is, oddly enough, socialism.

"That makes no sense," he was told.

He explained that when the Social Security Act was passed in the 1930s, and Medicare in the 1960s, Republicans opposed them both as socialism. They still use the word to oppose expansion of medicare. So what Democrats should do is ask DeSantis why he wants to get rid of Social Security and Medicare. He'll go crazy, because he knows that even among his most fanatical supporters, the same seniors who voted for Trump, the one thing that would kill him would be the idea of taking away Social Security and Medicare.

But when he protests that he would never in a thousand years get rid of Social Security and Medicare, you counter by saying that a lot of people think you would, because Republicans oppose socialism, and they originally opposed both of these socialistic ideas. Our source explained that it is the same trick Trump uses about the election. Say a lot of people are asking about fraud, even if you know they aren't, and after you repeat it a thousand times people will start believing it.

"But isn't that immoral?" he was asked.

"Don't be ridiculous. Morality has nothing to do with politics," he said. "If I were advising Florida Democrats, which I would never do unless they paid me, I would tell them to run ads imploring DeSantis not to get rid of Social Security and Medicare. When he says he has no intention of doing that, they say a lot of people are saying you will. When he says that's a crazy rumor, you bring up socialism and say if he's against socialism, how can he be for socialistic stuff like Social Security and Medicare? They can even say they know he wouldn't get rid of them, but he should clear up the rumor that a lot of people are spreading. And that way they keep spreading it. It works every time."

“Socialism.”

Watching the Olympics, and financial and political channels, makes one aware of the extent to which the sports lexicon has invaded other forms of human activity. Hardly five minutes go by without hearing an expression that originated on the playing fields of man or beast.

Watching the Olympics, and financial and political channels, makes one aware of the extent to which the sports lexicon has invaded other forms of human activity. Hardly five minutes go by without hearing an expression that originated on the playing fields of man or beast.

Baseball probably started it when a home run became any successful endeavor. President Roosevelt in the 1930s referred to his batting average on getting his historic agenda passed. The other day a TV reporter referred to major league supporters of the big lie propaganda. Three strikes and you're out pertains to any politician who commits multiple mistakes. Reporters throw a curve when they ask a politician who expects a question on the immigration disaster if he is messing around with that cute new intern. When the same politician is too hungover to make a speaking date of the Kiwanis lunch, he sends his PR man to pinch hit for him. If the same politician also likes boy interns, he may be called a switch hitter.

Football is not far behind. It has one expression that has come full circle. Hail Mary, a Catholic prayer, became a synonym for a miracle pass, such as Doug Flutie's winning bomb against Miami in 1984. The term has grown wings and now is used for any long chance situation. An NBC reporter chose it to describe the odds of Republicans voting for the elections bill. Inside the 20 has come to mean any effort that is in the home stretch (itself borrowed from horse racing, as is not their first rodeo from bronco busting). A quarterback is the recognized mastermind of a business or political situation. When a Republican Senator is asked what he really thinks of Donald Trump, he punts, changing the subject to the Mexican border.

Basketball has fewer contributions to regular speech but a full court press can mean an all-out effort to register voters, and a slam dunk has multiple applications.

Which brings us to our real theme. For the first time since 1908, the U.S. did not win a single medal in rowing. Not one — not even bronze — in a dozen men’s and women's events. It is an awful downfall from the days when John B. Kelly Sr. was a national hero for winning in the 1920 Olympics, or our men's eight-oared crews (usually our best college crew) won almost every Olympics from the ’20s to the ’50s. Since the 1960s all countries have sent all-star crews. Our women had won the eight for three straight Olympics. This year both men and women finished fourth. Despite the fact that high school and college rowing has never been more popular, our national image seems in decline. It was hard even to get results this year; maybe because the media prefers covering winners.

This writer was once a coxswain, back in high school. As a freshman I stood 4’10” and weighed 75 pounds, not exactly an offensive lineman's dimensions. But I was a natural coxswain. And just as I was becoming the best in the world, or at least on the Schuylkill River, I grew a foot and gained 30 pounds and the coach kicked me out of the boat. But everyone knows coxswains are a little weird, so to raise the rowing profile, here is a weird idea: Insert some popular rowing expressions in general discourse, as with baseball and football.

One of the more obvious Is to catch a crab, which happens when an oar goes into the water at an angle, rather than squared up. The oar slices deep and sends the oarsman sharply back and brings a whole crew almost to a halt. In smaller boats it can knock a rower out of the boat. It rarely happens with elite crews, but it did turn a boat over in the recent Olympics. It has great possibilities to describe any major screwup by a politician or anybody else. Another popular phrase is open water. It means when one racing shell is more than a length ahead of a rival. Open water between the boats. At standard distances, such a lead is rarely overcome. A candidate who polls more than 55 percent would have open water over their opponent.

A Power 10 is when the coxswain calls for the crew to row especially hard for 10 strokes at a key point in the race, hoping to build a lead or narrow one down. It could be used anytime a heightened effort is required. Perhaps the best of all is weigh enough — a command that goes back to Shakespeare, meaning to stop rowing immediately. It could be used for any circumstance where an individual must cease and desist. It would be a good way to silence someone like Matt Gaetz, or a super heavyweight wrestler who goes over 500 pounds. That person would be told to weigh enough.

And with that slam dunk of a dreadful pun, it may be the right time to weigh enough.