Congresswoman Debbie Wasserman Schultz has come to the aid of the beleaguered WAVE trolley—the one designed to solve Fort Lauderdale’s downtown traffic problems with 1890s technology. Schultz was quoted in the Sun-Sentinel to the effect that killing the WAVE deal, as recently elected city commissioners have vowed to do, would be a mistake. She says the city would have difficulty attracting federal money for any future projects. She added that the trolley is needed to relieve traffic. She also said the city had an obligation to those who made investments in downtown based on the expectation that the trolley was coming.

The strength of Ms. Schultz’s opinions has been weakened since her embarrassing removal as Democratic National Chairman after her committee was accused of favoritism in backing a candidate in the last presidential election, but she is probably right about a refusal to accept federal money leading to difficulty getting money in the future. But she is definitely wrong in saying the trolley will relieve congestion. No vehicle that blocks a lane of traffic is going to spell relief. It would be a different story if the trolley had a dedicated lane for its tracks, as new light rail systems have in other cities. The trolleys shoot right past lines of cars, encouraging people to abandon those cars in favor of the faster mode.

And the argument about investors is wrong. It’s the other way around. The WAVE was used as an excuse for developers to get approvals for overbuilding without consideration for the traffic problems—on the spurious grounds that the trolley would enable people to leave their cars at home.

With so much time and money already invested in the WAVE, is there no way out of this mess? There is. The city should accept the government money and send those pretty artists' renderings up to Washington—pictures that show a futuristic trolley on lightly traveled streets—and say the system is up and running and is a great success. Only we need some more money because the electric bills are higher than expected, and there have been expensive lawsuits from families whose breadwinners have committed suicide when frustrated by gridlocked traffic when trolleys stop to discharge and board riders.

Chances are that with Washington in such chaotic condition, nobody will challenge this effort, but if they do, there are several options:

(1) Say that stealing from the government is traditional, as many in the Trump administration have been proving.

(2) If someone challenges that reasoning as problematic, say we were victims of fake news and really meant to say that the WAVE concept has had some change orders. These include giving up the idea of tracks in the street and overhead wires in favor of compact electric vehicles that can get out of traffic when serving passengers and run on well-publicized busy streets so often that as in Chattanooga or Atlantic City (the century old jitneys are not electric) you don’t need to follow a schedule because you can almost always see one coming a few blocks away.

That should certainly satisfy the U.S. Secretary of Transportation—if there is one—and the enormous savings of replacing the trolley with efficient electric buses would give the city money to use on something that the public really wants and needs—such as bringing back Maguires Hill 16.

Image via

If Ed Kennedy had died 20 years ago, instead of living to the ripe old age of 87, his departure from this life two weeks ago would have warranted an important obituary in the newspapers, maybe even page one. But with newspapers hurting, and not that many people even reading obits in print these days, the former Broward County commissioner had to settle for a paid, not very long sendoff in the Sun-Sentinel.

The brief obit did cover the man’s salient achievement, however. It recounted how as a Broward County commissioner from 1984 to 1992, he was an early advocate of a commuter rail. He was not the earliest, we must note. Anne Kolb deserves that distinction when she was commissioner in the early 1970s, but her vision turned out to be a long way off. A decade later, it was Kennedy who managed to bring three counties, historically not known for cooperation, into the compact that resulted in Tri-Rail. That was in 1989, and for a time, Kennedy was much in the news as Tri-Rail got off to a rocky start with late trains and disappointing ridership.

We got to know the man at the time. We were writing a column for the late Hollywood Sun-Tattler, and being a train junkie, we followed the problems of a system that everybody, including Ed Kennedy, knew was on the wrong track. Its initial reliability was hampered by the fact that its dispatching was controlled by its landlord railroad—the CSX. And, as happens with Amtrak trains all around the country, railroads give priority to their own freight traffic, even if that makes passenger trains chronically late.

We were sympathetic to Kennedy and Tri-Rail, a rare voice of hope amid a chorus of criticism from much of the media. We wrote of the challenges of a commuter train that missed by a mile the downtowns all along its 71-mile CSX route, while the nearby FEC tracks, perfectly positioned to the east and penetrating the commercial centers of Delray Beach, Boca Raton, Fort Lauderdale, Hollywood and Miami, were used exclusively by slow-moving freight trains. We illustrated the problem by trying to talk to the FEC about the possibility of using its tracks for passengers. We waited for weeks for a return phone call, and when it came, it was the president of the railroad. The FEC did not even have a PR person. Didn’t need one. The president, in a gruffly amiable way, said “Sorry Mac, no interest in commuters. We’re a freight railroad.”

Ed Kennedy appreciated our efforts, and was always available—even to meet a few times after work at Danny’s Downtown, a short-lived restaurant bar owned by the late Danny Chichester. It was in one of downtown’s taller buildings at the corner of Broward and Andrews avenues. It is now that green Bank of America building. Despite the pressure he may have felt, Kennedy was always upbeat and calm. It took some time, but eventually, his confidence was rewarded as Tri-Rail overcame its startup problems and turned into a useful train, gradually building ridership to 16,000 daily, despite the handicap of being on a track to nowhere. Its southern terminus was in a seedy neighborhood near Miami International, miles from the city’s booming business center. That will soon be changed, as the service is scheduled to be re-routed (along FEC tracks) into the heart of the city.

Ed Kennedy lived long enough to see the seeds he struggled to plant in the 1980s bear promising fruit after the FEC changed ownership and decided to re-enter the passenger field with Brightline, the fast train planned to connect Miami to Orlando. With that breakthrough, it is anticipated that Tri-Rail will at last use the right track, routing some trains to serve the core of fast-growing downtowns all along its right of way. Recently, Brightline has even hinted it might even serve commuters, with additional stops between West Palm Beach and Miami.

Too many politicians leave behind them a legacy of self-serving deals, sometimes even jail time. Ed Kennedy leaves behind something of value. He may have outlived the accolade, but amiable Ed Kennedy deserves a fond farewell.

Image via

We all know the question about the one person in history we would most like to have dinner with or get to know a little bit. Would it be Judas Iscariot, Winston Churchill, Stormy Daniels? Those are all good choices, but not ours. We have long thought the person we would like to know better is Hugh McNeelis.

That’s how he spelled it—at least that’s what it says on his gravestone in Allentown, Pennsylvania. Other members of that clan have spelled it McNealis, McNelis, just plain Nelis and, in the case of one chap who moved to Australia—Nayliss. Hugh McNeelis is our great-great-grandfather, and we think of him this time of year and wonder how much he would enjoy what has become the season of St. Patrick.

He was not just another Irish immigrant. He was the first of our family to leave Ireland, in his case from Donegal. He lived about as far north as you can go. He came over in 1835, when he was 32 years old. This was a decade before the great wave of Irish immigration caused by the potato famine. But he did not stay long. He arrived with his newly married sister and brother-in-law, a fellow Donegal native named Tom McFadden. They landed in Brooklyn, New York, where the sister had a baby and died six months later. Hugh and Tom felt challenged with raising a baby, so they returned to Ireland.

They made it through the famine (four of mother’s great grandparents did not) and then re-emigrated around the time of the Civil War with the baby, also named Tom, now grown. Hugh McNeelis by then was married (to Tom McFadden’s sister) and had his own family, which he brought over all at once. That suggests he had more money than the average impoverished Irish immigrant. This time he settled in Allentown, where he owned a tailor shop.

That’s not unusual, for Donegal is famous for its tweed industry. But what was unusual was that Hugh McNeelis fancied genealogy—at a time when many Irish had never heard of the word. He kept records of every relative he could trace. Thus we know that his father was Michael McNeales, born around 1767. His mother was Catherine McCarron. Other names he traced to the 18th century include McFadden, of course, along with Sweeney (mother’s name) McGee, Gallagher, Campbell, Ward and Durning, all of Donegal. There is also O’Toole and O’Malley from County Mayo, Burke from Cavan and Ryan from Tipperary. The latter produced our most famous ancestor, Patrick John Ryan, who is believed to be a cousin of our great-grandmother. As a young priest he ministered to Confederate prisoners in St. Louis during the Civil War. He later was archbishop of Philadelphia from 1884 to 1912. He was a gifted orator and a charmer, credited with becoming friendly with the old line power structure and easing tensions between Irish Catholic immigrants and the Philadelphia Protestant establishment.

Hugh McNeelis lived long enough to know most of these relatives. At age 89 it took a train to kill him. He was struck by the Buffalo Express on the Lehigh Valley Railroad while bringing the cow home from pasture. By then he had passed along family records, including 19th-century photos, to his granddaughter, Kate McNealis (shown above as a young woman c. 1885). Her daughter Sara (Sweeney), our mother, updated them until her death in 1990.

And we wonder how old Hugh, who obviously had great pride in his Irish heritage, when earlier American settlers had contempt for the new immigrants, would feel today when a college football team takes pride in the name “Fighting Irish” and other teams go by names such as Celtics and Gaels. He did live long enough to see his countrymen literally fight their way toward respectability, partly because of their brilliant service in the Civil War. He knew that two young Gallagher relatives were among the many thousands of Irish who died preserving the Union.

But we still think he would be amazed to see Irish not just in the mainstream of American life, but celebrated each March as no other group in the country. Mick, once a slur, today offends few. Irish have become the symbol of American success. The name Kennedy has been described as American royalty. The surnames of people who once saw “No Irish Need Apply” signs have been adopted by more recent immigrants who want to appear American. No other group has family names prevalent as first names. Ryan, Bryan, Ward, Carroll, Kelly, Murphy, Nolan, Donovan, Grady, Connor, Riley, Murray, Neil—the list goes on. Most parents who select those names don’t even think of them as Irish.

This does not happen with other nationalities. You don’t find many people named Gaetano O’Brien, and for some reason Huizenga, Netanyahu and Putin have never really caught on as American first names.

It would be great fun to break bread, or share spirits, and discuss all this with Hugh McNeelis. Some day, God willing, we might. Until then, Stormy Daniels should suffice and might be nice.

A few weeks ago, the lead editorial in a Sunday edition of the Sun- Sentinel was one for the ages. It dealt with the extraordinary reaction by some South Florida political leaders to an extraordinary situation. Namely, the refusal of the state legislature to even consider a ban on military assault-style weapons in the wake of the Parkland tragedy, despite unprecedented appeals by so many people, including the eloquent Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School students, to do something about these weapons in the hands of unstable people.

The Sun-Sentinel applauded “local profiles in courage”—prominent South Florida leaders, and others in municipalities around the state, who are advocating what we might call “civic disobedience,” a government version of civil disobedience—defiance of the state government whose gun laws are dominated by redneck legislators who are either bought off directly by the National Rifle Association, or otherwise intimidated by the threat of political opposition in their next election. Among those saluted by the paper:

Coral Gables City Commissioner Frank Quesada and his colleagues for passing an assault weapons ban in that city—in defiance of a state law that local communities can’t pass gun control ordinances, and says such conduct is punishable by a $5,000 fine, removal from office and requirement to pay one’s own legal expenses.

Coral Springs Mayor Walter (Skip) Campbell, who is calling for a state initiative to ban assault weapons. He needs more than 700,000 signatures to get it on a ballot, but considering that polls show overwhelming support for gun control, that is possible.

Broward Commissioner Michael Udine, Parkland’s former mayor, who has been an outspoken advocate for an assault weapons ban.

Weston Mayor Dan Sterner, whose city commission is planning to sue the state to overturn present laws permitting such weapons. The Sun-Sentinel also cited Dania Beach and Boca Raton, who have passed resolutions calling for an assault weapons ban and other gun reforms.

The Sun-Sentinel showed its own courage by writing: “Many more communities need to join this overdue revolution.” It was, in effect, endorsing defiance of the state, encouraging civic disobedience. Later in the piece it added this strong assessment of the situation:

“This is an existential struggle between the gun lobby’s perverted idea of ‘freedom’ and the right of everyone else to freedom from fear and to life itself. To the NRA, ‘freedom’ means being able to manufacture, sell, buy and bear any weapon anywhere and anytime. If people die on that account, it’s the price of their ‘freedom.’”

Considering the decline of The Miami Herald’s circulation (and influence) in half of Broward and all of Palm Beach County, the Sun-Sentinel enjoys a monopoly over a broad stretch of the Gold Coast with the audience that still reads newspapers. That audience, although smaller than in the past, is still the power structure of the communities it serves.

Because the Sun-Sentinel’s circulation dies off around Delray Beach, our northern readers don’t often see it. But they have a consolation prize in the Palm Beach Post, whose opinions on the gun subject are in sync with the Sun-Sentinel. And they get a bonus with the popular local columnist, Frank Cerabino, who often adds a touch of humor to his insightful opinions on the subject of guns.

If the Sun-Sentinel’s editorial were designed to make people angry, it succeeded brilliantly. The only thing we might have added are the salaries earned by the NRA figures. Wayne LaPierre, the CEO, reportedly earns in the millions. Marion Hammer, the organization’s lobbyist who is credited with making Florida the leader in reckless gun-friendly laws was reported making in the hundreds of thousands—for relatively few actual working hours.

In the past, such a gutsy editorial from the Sun-Sentinel would have been close to shocking. But today, not so much, thanks to the leadership of Rosemary O’Hara, editorial page editor (above). In the opinion of the many newspaper people in the area, this woman has been one of the best things that have happened to local journalism in years.

Dan Christensen, former Miami Herald reporter who does the Florida Bulldog blog, an investigative outlet that has filled a void left when newspapers cut staff drastically, shares a common view with Ms. O’Hara: “She’s almost single-handedly brought respectability to the paper’s editorial page with her strong, thoroughly researched editorials. A side benefit is that she’s boosting the paper’s image in the community even as it dwindles in size and coverage.”

Well done, Ms. O’Hara. Well done, Sun-Sentinel.

Image courtesy of Rosemary O'Hara

Jimmy Fazio, the late restaurateur who knew how to navigate the rougher waters of life, had just been paid a visit by the cops. This was in Wally's Olde Town Chop House back in the mid-1990s. The place is now called Himmarshee Public House.

The police visit had resulted from a complaint by one of Fazio's business associates.

"They said Mr. M----- said that I had threatened to kill him," Fazio reported. "They asked, 'Did you threaten to kill him?’ I told them, 'No, I never threatened to effin' kill him.' They said, 'Did you threaten him in any way?' I said, 'Yes, I threatened to break his effin' legs.’ ‘Oh,’ they said, ‘That's OK.’ So Bernie, be sure to never threaten to kill anybody, but it's OK to threaten to break their legs.' "

This picaresque tale may be amusing, but it applies to a situation that is anything but funny. It is a defense mechanism to prevent us from writing anything extreme about the punishment deserved by those we consider accomplices to the murder of 17 people in our county last week.

This awful incident was not just close to home. It was home. There are not many people around here who have not been personally affected by the latest mass shooting. In our case, one of Gulfstream Media's oldest and most valued employees, art director Craig Cottrell, had a kid and a nephew at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School. Thank God they were not victims. His daughter escaped by climbing over a fence.

One of the students killed is the daughter of the lacrosse coach at St. Thomas Aquinas High School, which our grandchildren attend. Another victim was Douglas' cross-country coach, whose team competes against our talented grandsons at St. Thomas.

The anger here is therefore more immediate and personal that any of the other mass shootings. And the accomplices to murder are close enough to be reminded of Jimmy Fazio's advice. They are all the Florida politicians on both the state and federal level who are prostitutes for the NRA. They take campaign contributions which amount to bribes. That money is legal, but it should not be. It is blood money. Some observers have noted that it isn’t all about money. There is also the fear that the NRA will use the same dollars to defeat any candidate it can’t control, and will fund a primary challenge to those who defy it. Either way, the politicians are afraid to cross this organization which is funded by the arms industry.

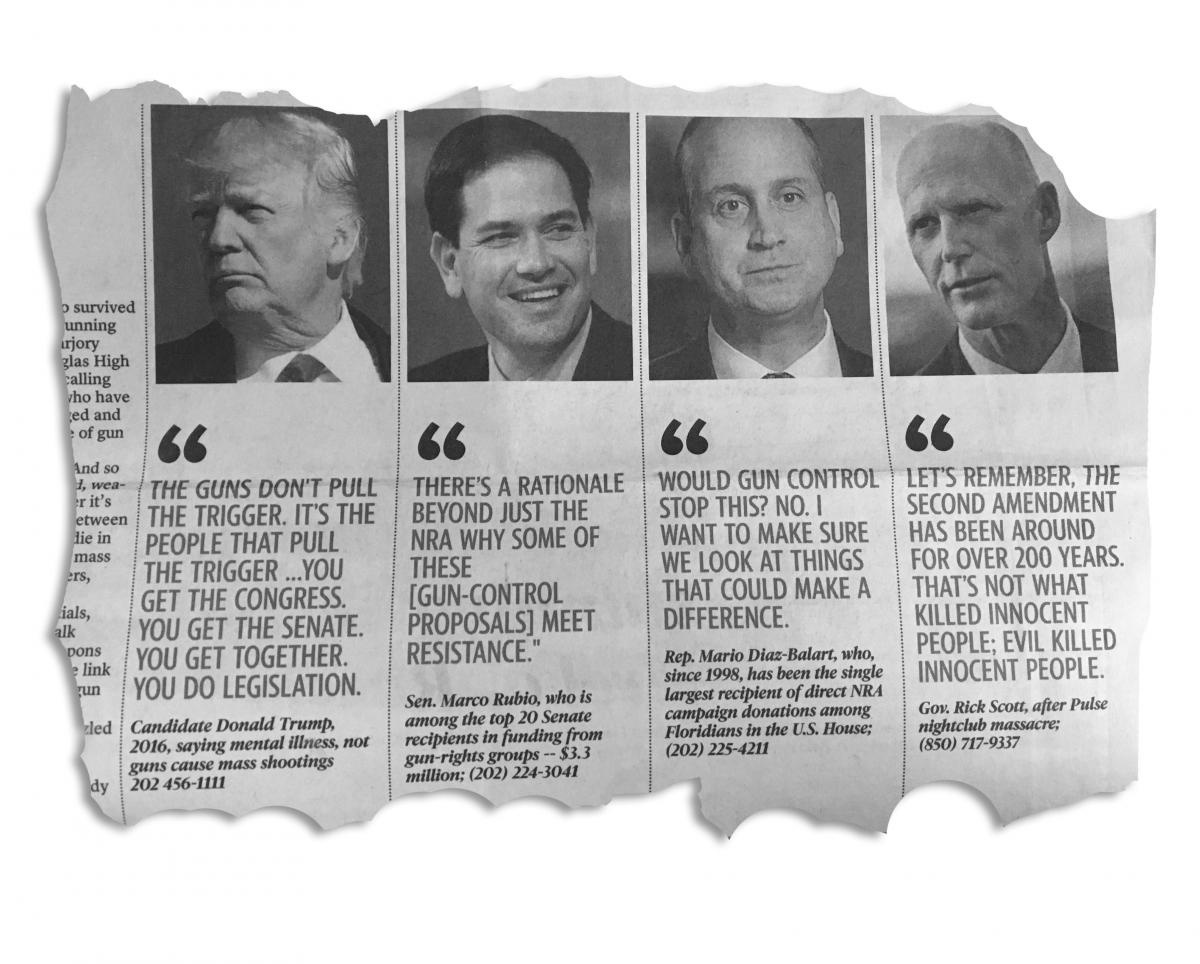

Sunday’s Miami Herald ran the photos of nine of these politicians, beginning with President Trump, which looked almost like a “Most Wanted” poster. Such condemnation leads to hope that perhaps our local tragedy may prove a tipping point.

"Maybe this time it will be different, maybe this time people will be so angry that something will happen." So spoke our colleague Craig Cottrell, father and uncle of two students at Douglas. We would like to think so, but the early reaction seems to be terribly familiar. The local response has been uniformly admirable. Saturday's Sun-Sentinel caught the mood. There was a lead op-ed piece by Gary Farmer, Broward state senator, calling for gun control. His piece concluded with seething determination:

"As legislators and parents, we will not rest until we can ensure the safety of our children and communities. We will fight tooth and nail against every dangerous and nonsensical pro-gun piece of legislation in the legislature. We will not allow our legislature to act as a contributing factor for the terrifying violence that we saw this week, and we demand that our fellow legislators do the same."

In the same section Broward Commissioner Michael Udine, whose district includes Parkland, wrote "...in addition, we must demand that Congress enact an assault weapons ban that includes AR-15 semi-automatic rifles and further background checks. Any issue whatsoever that comes up in someone's background should be investigated before they can obtain a gun."

Even more telling were nine letters to the editor. One was a short pious "praying for you" thought. The other eight all called for gun control or voting out those paid-off legislators who block sensible laws. There was no sign of the usual second amendment rights BS.

That was here. Elsewhere, the early returns showed the usual NRA lackeys reaction to such tragedies. President Trump made a publicity trip to say this was bad and praised the first responders and health care workers, but there was no mention of gun control. It was more of the same with Sen. Marco Rubio, House Speaker Paul Ryan, State Senate President Joe Negron, who all called for action, especially in the area of mental health and increased school security, but did not touch the obvious problem—the existence of military-style weapons in the hands of anyone except combat troops.

The mental health issue is simply a way of avoiding the truth. And the same Sun-Sentinel page handled that canard beautifully. Surely the young man who confessed to the murders is mentally ill. Steve Ronik, the highly respected CEO of Henderson Mental Health Clinic, whose organization had contact with the shooter, and did not consider him an immediate threat, wrote that the percentage of violent crimes by the mentally ill is very small. He identified the real problem—that the mentally ill can get their hands on the weapons that even the sanest person should not possess in civilian life.

But newspaper articles are not going to solve the problem. And since Jimmy Fazio’s advice to threaten to only break their legs is probably illegal, even in Florida, where do we go from here?

We go back to the west of Ireland, 1880, when Charles Parnell suggested to angry Irish who wanted to kill a hated landlord, Charles Boycott, that a better, more Christian solution was to “shun” the man.

And they did. No restaurant would serve him; no carriage driver would transport him; no servant would work at his house; no field hand would harvest his field; no one would even speak to him. People crossed the street when they saw him coming. It worked. He could not even get a driver to take him to the train when he left for his native England. He left Ireland and he left the English language with the word “boycott.”

So it should be with these NRA bribe takers. They should be met with contempt at every turn. Do not honor them with invitations. Boo when they are introduced. Call the Hessian bastards exactly what they are—accomplices to murder. Make their lives unlivable, as the better angels of the Irish nature did to Charles Boycott so many years ago.

And, of course, vote them out of office, early and often.

A tourist walks into a bar and asks for a Bud. Bartender hands him a bottle of Miller.

“I asked for Budweiser,” man says.

“That is Budweiser,” replies the bartender.

That exchange used to happen on a regular basis in Fort Lauderdale, especially in its busiest neighborhood bars. The reason: William Thies & Sons, the local Miller Beer distributor, had developed such a close relationship with its best customers that a number of bars did not even carry Budweiser. Back in the 1960s, when Budweiser was the dominant beer in most of the country, it failed to keep pace with local customers’ needs when the crush of college spring break caused bars to run out of product and need a resupply fast.

When Budweiser was slow in response, William Thies & Sons made sure that Miller was available during the busiest times. Some of the most popular bars rewarded that service by refusing to carry its rival.

Bill Thies, who as a young man built that remarkable relationship after he took over the business when his father died suddenly at age 53 in 1964, died Tuesday at age 80. He had been in failing health for several years and did not recover from the effects of pneumonia over the Christmas holidays.

Thies and his brother-in-law, Bob Blaikie, were a Mr. Inside and Mr. Outside team. Blaikie was at the company plant in Wilton Manors, watching the books and keeping the trucks rolling. Thies was mostly on the outside, knowing the customers and expanding the company’s business. His friendly nature and big personality made him a natural salesman, and one of the best known figures in the bar and restaurant industry. He was on a first-name basis with countless bar owners and their staffs.

“My father never told me I couldn’t enjoy my job,” he liked to say.

The company’s market was large, stretching from Broward County to Vero Beach. Thies’ younger brother Dennis, known as Dee, ran the business north of Broward County. The company had a second distribution center in Lake Worth. It eventually expanded to include distributorships in Fort Myers and Sarasota. The brothers (Bill is on the left) are shown in a photo that first appeared in Gold Coast magazine in the 1970s, and was repeated in the magazine’s 50th-anniversary issue in 2015.

It did not hurt the business that the Thies family was well connected in Fort Lauderdale. The family came to Florida from Washington, D.C. in 1948 and got the Miller franchise in 1951. Bill attended St. Anthony School and Central Catholic High School (now St. Thomas Aquinas) where he was a three-sport athlete. He attended Notre Dame for two years and left when he married and joined the army. He was 26 when he took over the family business.

The company capitalized on the popularity of Miller Lite in the 1970s. Before it was sold in 2001, it had expanded to carry numerous brands, including Heineken beer. Thies had seven children and was joined in the business by his sons, Bill Jr. and Jim, who also joined him in real estate investments. A daughter, Krista Marx, is a judge in Palm Beach County. Other family members live in South Florida and Hawaii.

In retirement he became a private investor. He and his son Bill were shareholders in Gulfstream Media Group, publisher of Gold Coast magazine, when the company reorganized in the mid-1990s. Among the real estate investments was a Christmas tree farm in Blowing Rock, North Carolina.

A funeral mass will be held at 11:30 a.m. on Tuesday, Jan. 30 at St. John the Baptist Church in Fort Lauderdale. In lieu of flowers, contributions may be made in Bill’s name to the St. Anthony Friends for Education, 920 NE Third St., Fort Lauderdale, online at saintanthonyschoolfl.org/give-now-2/ or call 954.467.9009.

Our latest project, with the working title "All The President's Women," will be groundbreaking for its use of language. We plan to set a record for dirty words. That is going to be a challenge, for in the last few years words we would not use outside of locker rooms—and men’s locker rooms at that—have become commonplace in the media, including national television.

Not long ago certain expressions for bodily functions, or places where they normally occurred, were considered vulgar. You bloody wouldn’t use them when being introduced to the queen. But in recent years they have become bloody common, almost to the point that they are losing their shock value.

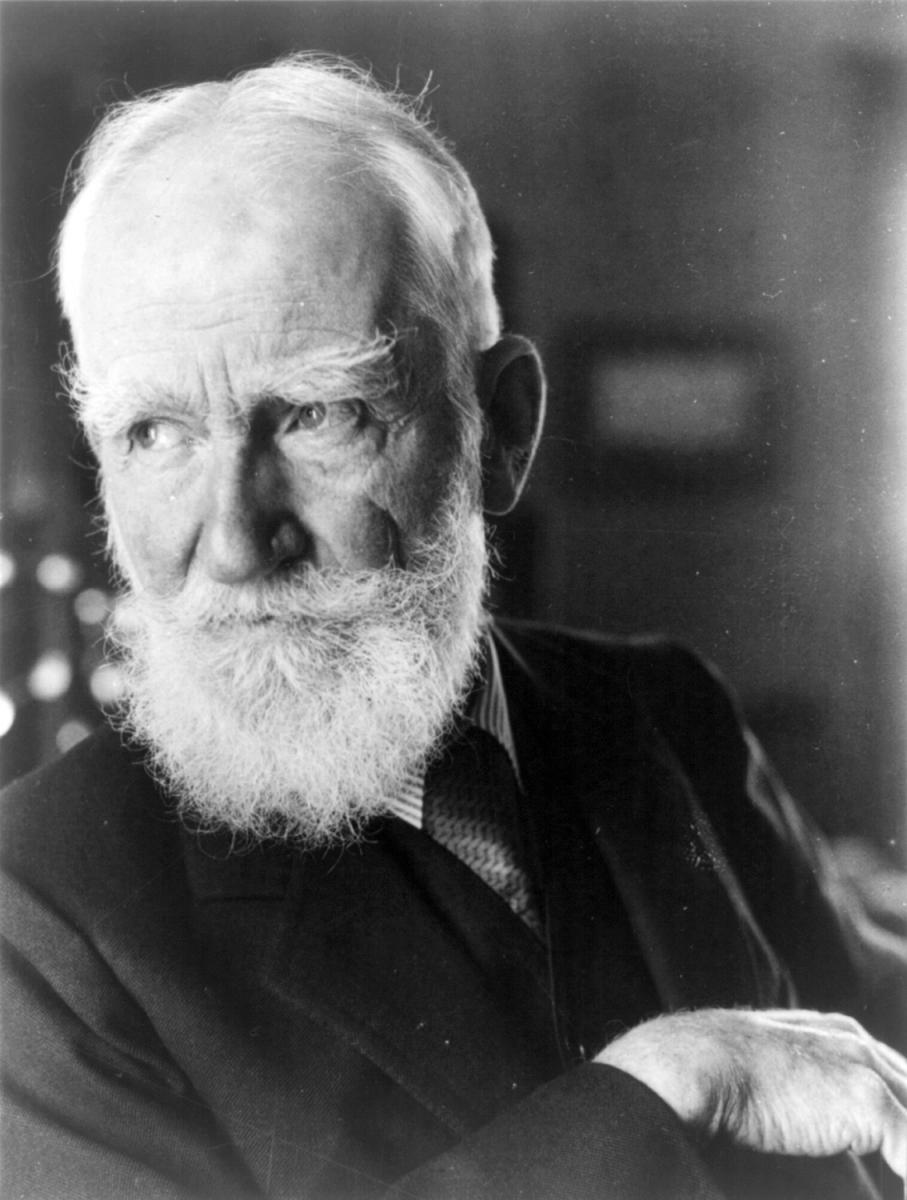

Which brings us to the word “bloody” and the memories of the best teacher we ever had. His name was Dan Rodden. He taught English at La Salle and began every course by spending the first two weeks dissecting word by bloody word a definition of art. “Art is intellectual recreation achieved through the contemplation of order.”

It would take us two weeks to repeat those lectures, so let’s move on. Dan Rodden ran our college theater, which was strong in musicals and at one time had quite a nice little reputation in Philadelphia. After rehearsals, he went drinking with his student performers, which meant he sometimes felt and looked bloody awful in the morning. It was a mood he carried into the classroom. With that being said, he was a delightful teacher and the man who first explained to us that when vulgar language becomes too common, it loses its shock value.

In teaching a course on theater, he mentioned a George Bernard Shaw play. We forget which one, but it was probably “Pygmalion,” which decades later inspired the musical “My Fair Lady.” In it, a character used the word “bloody.” Rodden pointed out that at the time (1913) the word was never used in polite British society. Rodden said this was like using the word “s**t” in our time. Our time, of course, being the1950s. It shocked the British audiences and helped mold Shaw’s image as a literary rebel.

That revelation amused us, as it still does most people in the U.S. Here, the word is regarded as just another example of British slangish, like “bloke” or “mate.“ But it still is regarded in Britain and parts of Australia as rather lowlife and used only by the culturally inadequate.

And so it may be with some of the crude words, now emanating from Washington sources that are increasingly polluting our national discourse on events, and in venues that deserve more refined expression. Which is why we need to come up with all the bad words we can think of and put them in a single historical source. And use them while they’re still bloody good and dirty.

Image via

“The Post” is a movie that could not miss being a winner. Not with Steven Spielberg directing two of the best actors of our time—Tom Hanks and Meryl Streep. It doesn’t hurt that the story is an important piece of journalism history, and part of a genre ennobled by a classic—“All The President’s Men.”

Aside from its artistic value, what we appreciate about this film is its timing. It makes every serious journalist, especially newspaper people, proud of their calling. It validates, almost to the point of glorification, a profession that has been shamefully attacked by that miscreant in the White House, whose actions have been affirmed by the scummiest of his political associates and by that paragon of fake news called Fox News.

As journalism history, critics have observed that the film gives too much credit to The Washington Post for exposing the Pentagon Papers, somewhat downplaying The New York Times, which owned that story and won a Pulitzer Prize for its work. Nonetheless, it is excellent drama and should do for the Pentagon Papers what “All the President’s Men” did for Watergate.

The latter film appeared shortly after Watergate took down a president, yet until the movie brought it all to life, a lot of people had difficulty understanding what all the fuss was about. To many, it seemed like just another political dirty trick gone wrong. The Pentagon Papers incident pre-dated Watergate and for most people it was also a vague affair, relating to a war that people just wanted out of, anyway we could.

But it was hardly a unanimous sentiment. Many of us had been through years of brainwashing, going back to the French defeat in North Vietnam in 1954, afraid that if South Vietnam went Communist, all of Southeast Asia would soon follow. The “domino effect” was a concept people could grasp. It was easier to understand than a nationalist movement, which was affecting countries that had enjoyed European civilization for hundreds of years. It was inconceivable in the early 1970s that one day American veterans would return to Vietnam as tourists and be warmly greeted by those who once tried to kill them.

The Pentagon Papers are more readily understood with the perspective of four decades and the reality of a war that has been brought home numerous times in books and films such as “The Deer Hunter,” “Platoon” and “Apocalypse Now” and its memory hardened in granite on the National Mall. That wall is a reminder of an afternoon in 1969 in a cemetery just outside Philadelphia when an honor guard of his friends, still in uniform, lowered Lenny Martin to his grave, and the sun suddenly burst through on a day that had been wet and gloomy.

What Daniel Ellsberg revealed when he leaked the Pentagon Papers is that Lenny Martin and more than 50,000 others had died in vain and that the government suspected it all along. In that respect “The Post” goes a bridge too far. It lumps four presidents, going back to Eisenhower, as sort of conspirators who deceived the American people on the reality of that war. That is unfair to at least one. Although he initially sent in American forces as military advisors, President Kennedy was on record as a young senator in the 1950s to the effect that European colonies, such as the one France had, were doomed. As president, he had begun to realize that further military involvement was a mistake. After the Bay of Pigs disaster in 1961 and the tension of the Cuban Missile Crisis a year later, he had lost confidence in the CIA and some of our highest-ranking military men. He told confidants that he planned to withdraw from Vietnam after he won re-election. He also angered the military-industrial establishment by reaching out to the Soviet Union in an effort to end the Cold War.

As with the Pentagon Papers, time can be history’s clarifier, and it is increasingly clear that John F. Kennedy was one more casualty of Vietnam

Image via

There are at least 30 local magazines in the same Florida markets (Gold Coast and Treasure Coast) that once had only a few. It is doubtful that many of them would exist today had it not been for the example set in Philadelphia some 60 years ago. That was when an obscure publication called Greater Philadelphia Magazine began to evolve into the first important city magazine, virtually inventing a new media form that has been copied in hundreds of cities, large and small.

Greater Philadelphia dropped the Greater in the mid-1960s, and as Philadelphia it cast the mold for what are now important media voices such as New York magazine, Washingtonian and Texas Monthly, as well as less punchy magazines all over the country. In our lifetime only a few people can claim to have invented something new in the print communications field. Jimmy Breslin, who died in March, was one. He created the “news column”—applying the license and artistry of a columnist to the leading news stories of the day. D. Herbert Lipson, who died Christmas morning, was another (shown above on the right with Alan Halpern in the late 1950s). He is the man who invented the city magazine.

Well, to be historically accurate for the dwindling number of people who care about such things, he should be termed co-inventor. For Herb Lipson, fresh out of Lafayette College, joined his father’s company at almost exactly the same time as Alan Halpern. And many people who worked for him, including this writer, considered Halpern, a gifted editor, as the man with the vision to turn a Chamber of Commerce organ into a groundbreaking magazine.

But, as we pointed out in our bookazine, “The Philadelphia Magazine Story,” which published in 2013, the writer most influential in Philadelphia’s dramatic growth in the 1960s, thought otherwise. Gaeton Fonzi, who joined the magazine in 1959, wrote most of the blockbuster stories that built the magazine’s reputation throughout the next decade. He recalled that it was Lipson who pushed for the transformation of a publication, which survived by selling its cover as advertising into a hard-hitting, must-read magazine.

He encouraged Fonzi to do the first stories that attracted new readers as the magazine grew in a few years from a free distribution of 15,000 to a paid circulation of nearly 100,000. As we wrote several years ago: “Lipson had a vision of what the magazine could become and the sense to give Halpern largely a free hand, and to support him in running stories that took considerable courage and exposed him to legal risk.”

Those stories included the expose of a crooked reporter at The Philadelphia Inquirer who used his reputation as a hatchet man for the paper’s feared publisher, Walter Annenberg, to shake down numerous businesses, including the city’s largest bank. That story landed the reporter in jail, where he died. It also led to Fonzi’s book on the disgraced Annenberg, which appeared to prompt him to sell the paper to Miami-based Knight-Ridder a few years later.

By that time Herb Lipson had expanded to Boston, where Boston magazine still thrives. That was actually our idea, and we helped him launch it at the same time we were preparing a move to Florida.

Fonzi, who later joined us in Florida and was editor of Miami Magazine in the 1970s, also began his acclaimed work on the Kennedy assassination at Philadelphia. He interviewed Arlen Specter, then an assistant district attorney, shortly after the Warren Commission published its controversial finding that a lone assassin killed JFK. Specter had received considerable publicity, initially favorable, for his work on the Commission. To Fonzi’s amazement, Specter, later at U.S. Senator, could not explain his own theory of the “magic bullet” that underpinned the lone gunman conclusion.

Our first journalistic assignment in Florida was made in the company of Herb Lipson. We stayed at the Boca Raton Resort and Club and met with the former publisher of the defunct Philadelphia Record at his Palm Beach home. J. David Stern was celebrated for shutting down his paper after a newspaper strike by the very union he had helped create. Lipson was known for taking such fun trips with writers. He had more than a little playboy in him in his early years, manifested on that trip when he insisted we visit Fort Lauderdale to check out the sexy girls at a restaurant called the Mai-Kai.

He later spent the last of his 88 winters partly in Florida in the Naples area. When Gold Coast celebrated its 50th anniversary in 2015, we invited him over for the event. We thought it would be fun to introduce the man who started it all. He politely declined, saying we would meet at another time.

The release of the long-sealed files on the murder of President Kennedy has produced little new information. Those of us (we few, unhappy few band of doubters) who have been following this cover-up of a presidential assassination for the last 50 years, were not actually expecting to find a file labeled: “How We Knocked Off A President and Got Away With It.” The people who committed this crime have had ample time to make sure no incriminating documents survive.

However, one interesting detail long known to those who have studied the crime was reinforced. Documents make it clear that within days of the assassination Lyndon B. Johnson’s White House and Robert Kennedy’s attorney general’s office wanted to be sure that Lee Harvey Oswald alone be blamed for the crime. They may have had different motives, but for both, it was a priority that any talk of a conspiracy be immediately squelched. The Warren Commission’s job was to do exactly that. And it did.

Still, it is puzzling that some parties still object to releasing all the documents relating to JFK. And those they have released are teasers. They tend to have crucial parts missing, especially references to the CIA and other aspects of our intelligence network. Researchers think those withheld documents may confirm that Oswald was both a CIA and an FBI operative, which shatters the Warren Commission portrait of him as a pro-Castro communist sympathizer. It also supports the principal conspiracy theory: Oswald was a “useful idiot” whose role was to take the blame (and a bullet) as part of a high level government hit.

If one thinks the refusal of government sources to give up documents to the public is something of the past, think again. And listen to Dan Christensen. Christensen (above) is the founding editor of Florida Bulldog, an independent news organization whose work is often picked up by local papers. He is a former Miami Herald reporter. Florida Bulldog celebrated its eighth anniversary last week with a party at YOLO on Las Olas Boulevard.

For six of those eight years Christensen has been waging a campaign to get the FBI to release what it knows about a Sarasota Saudi Arabian family that was visited by some of the 9/11 hijackers prior to the 9/11 attacks—perhaps the only event to compare to the Kennedy Assassination, and infinitely greater in the death toll.

The Sarasota Saudis were connected to the Saudi royal family and disappeared in a hurry (they left their cars and other belongings) shortly before 9/11. The obvious questions: Were Saudi royals behind the 9/11 attacks? Does our government know it? Did they conceal it?

The FBI never told the 9/11 Commission about the Sarasota Saudi connection, which has angered former Florida Sen. Bob Graham, a member of the commission who has been working with Florida Bulldog to find out why such dramatic information was concealed. Slowly, and only with constant legal pressure, has it been revealed that the FBI had a report on the matter, but never told the 9/11 Commission, and has for six years resisted the efforts to make it come clean. Christensen likens it to the Kennedy Assassination files.

“It’s worse, if that’s possible,” Christensen says. “Say what you want, one thing the Warren Commission did was they laid everything out. There were 26 volumes of evidence, and nothing was blocked by black tape. It was all there. But now (on the Saudi matter), very little is laid out, and there is no documentation. Much of it is being held for a variety of reasons. It’s a completely different ball game.”

“We see that lies have been told,” Christensen adds. “It’s what Bob Graham calls ‘aggressive deception.’ They [The FBI] are actively lying to us since 2011. First, they said they notified Congress [about the Sarasota Arabs]. Well, we have demolished the argument that they told Congress. We found documents in their files that showed there were many connections between the Sarasota Saudis and the hijackers.”

Florida Bulldog has lived up to its name with its dogged legal efforts, resisted by the government at every turn. Bulldog has been seeking information, which is redacted in the FBI files that have been released, especially those concerned with funding for the 9/11 terrorists. Christensen thinks that ties in with the Sarasota Arabs and their contacts with the hijackers.

There is an interesting connection between Florida Bulldog’s quest and the JFK assassination researchers. The Sarasota matter first came to Christensen’s attention through an Irish investigative reporter, Tony Summers. That’s the same man who was friendly with our late colleague, Gaeton Fonzi, whose The Last Investigation is regarded as one of the best books on the Kennedy Assassination.

Summers, who wrote his own book on the assassination, was influenced by Fonzi’s work in the early 1980s. It was after Fonzi’s book first appeared as two long magazine articles in Gold Coast magazine.

Fonzi was in contact with Summers until his death in 2012, and his widow Marie continues that connection.

She and Summers are among the more prominent of the club of "we few, unhappy band of doubters."