One of our communicants is a great fan of President Trump. He admires him for saying what he means and doing what he says, for his military service while in high school, as well as his respect for women and Puerto Ricans. He also enjoys football, but had a power failure and missed the big game. He called to find out who won.

“Miami won, 41-8,” we said.

“Shut up. You must mean Notre Dame won 41-8.”

“No, Miami.”

“That’s impossible. God would not allow it. How do you know?”

“Saw it. Besides, it was in the papers.”

“It must be fake news. You can’t trust the media. They’re the enemy of the people. Where did you see it?”

“It was in The New York Times.”

“Oh, it’s definitely fake news. They never tell the truth. Who really won?”

“It was also on Fox News.”

“It was. My God, it must be true then. How could it happen?”

“Easy. Miami wore their good old orange jerseys and traditional white helmets, and Notre Dame stunk up the joint. It could have been the other way around, except for about a dozen plays.”

“Did Sean Hannity confirm this?”

“Haven’t heard. I know he’s been busy with that child molester fuss, or something.”

“What’s that all about, anyway?”

“Guy running for office in Alabama. They say he likes teenage girls.”

“Who doesn’t?”

“Some like teenage boys.”

“Some like Foxy girls. Until they sue.”

“Some like both. Anyway, that’s the real score.”

“You mean the game?”

“Alas, yes. God’s will be undone.”

Image via

The addiction known as Notre Dame is returning to South Florida to play UM in a game that is as of old—a clash between two highly ranked teams that could bear on the national championship. Although the game is at home for the Hurricanes, it isn’t much of an advantage, for Notre Dame has a powerful following in South Florida. Hell, it has a powerful following all over the country, wherever faith and football intersect. Still, there aren’t many markets so distant from South Bend that have so many influential alums in residence. And all, needless to say, are football fans.

You can start with Fort Lauderdale Mayor Jack Seiler, but the Irish connection goes back long before Seiler was born. Consider Governor R.H. Gore, who came to Florida in the 1920s and built the newspaper now known as the Sun-Sentinel. Gore (who was governor of Puerto Rico, not Florida) did not go to college, but he lived in Indiana and was a Notre Dame admirer. He sent six of his nine children to Notre Dame, and members of more recent generations have followed. He died in 1972, at a time when his sons Jack and Ted Gore were top executives at the newspaper.

By then local athletes had become part of the Notre Dame football lore. Longtime U.S. District Judge William Zloch was a quarterback under legendary coach Ara Parseghian in the 1960s. Before that he was in the same backfield as the storied Brian Piccolo at Central Catholic, now known as St. Thomas Aquinas, a nationally recognized high school football power. His two brothers, Chuck and Jim, also played football for the Irish.

They were contemporaries of Notre Dame alums who starred for the young Miami Dolphins when it became pro football’s only undefeated team. Linemen Bob Kuechenberg and Nick Buoniconti both had distinguished Florida careers after football.

A number of local players have followed their path, notably Autry Denson, from Nova High School who became Notre Dame's all-time leading rusher. After several years in the pros, he began his coaching career here on a high school level. Denson is back at Notre Dame coaching running backs.

Football isn’t the only sport associated locally with the Golden Dome. The late Jimmy Evert was captain of Notre Dame’s tennis team before he became a noted South Florida coach, whose star pupil was his daughter Chris.

ND grads are found all over the South Florida business world. One of the area’s oldest retailers, men’s clothier Maus & Hoffman, had three Notre Dame brothers working together—Bill, Tom (deceased) and John—along with a few members of the next generation. Bob Moorman, Notre Dame ‘73, heads another old Las Olas retailer, Carroll’s Jewelers. Anyone hungry for more can go to any of the chain of Quarterdeck restaurants, owned by Paul Flanigan, another grad from the 1970s.

Notre Dame has an unusual presence in local publishing. Aside from the Sun-Sentinel history, three of the leading South Florida magazines have had Domers (as in golden dome, above) as chief executives. The late Ron Woods was the owner of Palm Beach Illustrated; John Shuff is owner/publisher of Boca Raton Magazine; and Mark McCormick is president of Gulfstream Media Group, which publishes six titles, including Gold Coast magazine.

Notre Dame clubs (there are five in South Florida) are about much more than football. They raise scholarship money and support local charities. Their local dinners are invariably well attended, and football isn’t their only draw. They are present in numbers when the Notre Dame Glee Club makes its periodic trips to the area. The singers’ next visit comes up in March. You know the Irish will turn out for their famous fight song—especially if they win Saturday.

Image via

Recall the scene from “Gone with the Wind” when an older couple sees the names of their sons listed among the dead following a big Civil War battle? The posting of the dead and wounded in such public places as train stations was common in the Civil War because that’s where the telegraph offices were located. It was one of the more realistic touches in a film that had its share of romantic license. The newspapers picked up their information on casualties that way, or from dispatches from their own correspondents posted with most units.

We learned that some years back when visiting the national archives to try and get information on our Gallagher ancestors, John and James. They were our great grandmother’s younger brothers, and the family history says simply that they died in the Civil War. No dates or battle information has come down. We think they lived near Easton, Pennsylvania, for that is where their sister was married in 1854. Census records show two young Gallagher men with the right names living in an Irish shantytown along the Lehigh River in 1860. Are they our boys? We will likely never know. There were 120 men in the Civil War from Pennsylvania with the names John or James Gallagher.

At the archives we discovered that aside from unit records, such as payroll, pension and discharge papers, little information about the average soldier existed. There were no home addresses, next of kin, etc. We asked a worker at the archives how the government notified families when men were killed. He said the government did not. Newspapers, which were with the units in battle, sent that sad information home. Unless a family saved such materials or kept letters from soldiers or their friends, many of those lost in battle were gone with the wind.

But the face of battle has changed.

Witness the recent deaths of a Florida soldier and three comrades in Niger. It led to a controversy over President Trump’s condolence message to the wife of the Florida man. There have been demands for information on the circumstances of his death—looking for someone to blame. The government is right to be cautious in revealing that kind of stuff about what is obviously a sensitive and necessarily guarded anti-terror mission.

The young widow complained that she was not permitted to see her husband’s body. There is a good reason for that. We have previously written about covering a Vietnam funeral when we were able to sit in on the instruction class at Dover Air Force base for soldiers assigned to escort bodies home for funerals. The escorts were told that if a body were listed as “non-viewable” it meant exactly that. They were told that there were women in mental institutions because they insisted on seeing a body of a husband or son disfigured beyond recognition. If the family insisted on opening the casket, the escorts were told to leave the room.

Such has been the intensity of the focus on the recent deaths that some have wondered if the Florida soldier could have been killed by friendly fire. That stems from the case of former pro football player Pat Tillman who was killed in Afghanistan. It was not initially revealed that he was probably killed by our own troops—as if that is some kind of crime. Hardly. Men have killed comrades in the fog of battle since wars began. A notable case was Gen. Thomas (Stonewall) Jackson, fatally wounded in the dark by a Confederate sentry during the battle of Chancellorsville in 1863. Such friendly fire deaths are rarely documented, and sometimes it takes years. In a case in our family, it was about 70 years before we learned that our cousin, Lt. Thomas McCormick, a Navy pilot who died at Iwo Jima in 1945, was likely such a victim.

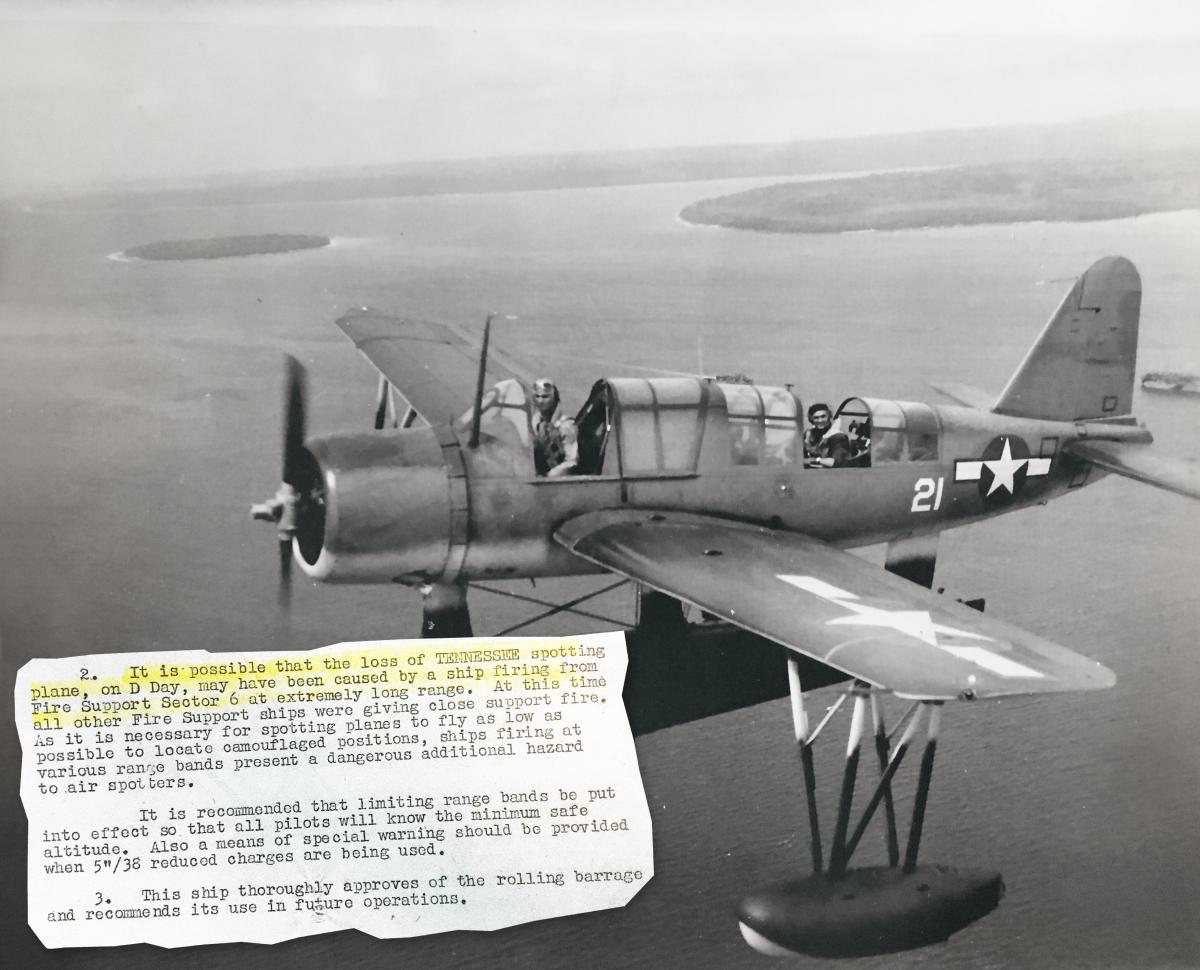

We learned that in the strangest way. As far as we know, Tommy’s mother in Atlantic City (his parents were separated) received only the usual “missing in action” telegram. We don’t think his commanding officer, or any friend, ever contacted her with more information, which usually happened in World War II. Tommy flew the OS2U Kingfisher, a floatplane launched by catapult from the battleship Tennessee. His job was to fly at low altitude to observe fire for the ship’s big guns, which were supporting the Marines’ landing. The ship’s log, which we did not check out until years later, noted that his plane was seen crashing with its tail section missing. There was no explosion in the air or enemy planes that could have shot it down.

A few years ago we contacted Paul Dawson, who runs the U.S.S. Tennessee Museum in Huntsville, Tennessee. To our amazement he knew who Tommy McCormick was and had photos of him in his aircraft (above). It turns out Dawson’s father had been the ship’s photographer, and he saved photos of the handful of pilots on the battleship. He knew them because he sometimes did aerial photos from their planes. Knowing of our interest, Paul Dawson subsequently discovered information that cast light on Tommy McCormick’s last flight.

He discovered an after-battle report marked “confidential,” which human eyes had probably not seen for seven decades. It was secret at the time for obvious reasons, for it told what had gone right and wrong aboard the ship at Iwo Jima.

The report said that a “projectile” had been seen striking Tommy’s aircraft, breaking it in two without exploding. Then, in the closing summary came this revelation: It was possible Tommy’s plane was hit by a large shell from one of our own ships firing at a higher angle than expected. It would have gone through the small plane flying at low altitude without exploding.

From what we know of the military, if the Navy suspected that friendly fire downed the plane, it probably was pretty sure that’s what happened.

Such is the fog of war, even on a clear day in February 1945.

The most recent Ken Burns documentary on the Vietnam War is a much-acclaimed history of an event that most Americans may never fully understand. Unlike recent controversies about Civil War memorials, a war with which no one alive today has personal experience, there are millions who lived through the several decades when Vietnam evolved from a place vaguely known as French Indochina to an epic tragedy for hundreds of thousands of Americans, and for those who fought against us.

For most, Vietnam began in the mid-1960s when our military presence grew from a few Special Forces and advisors to hundreds of thousands of soldiers. But the roots of that conflict trace back to 1954 when the French were defeated at Dien Bien Phu. Most of us took little notice, for we were just getting over the Korean War.

But not long after, the name Vietnam became better known, thanks to an ex- Navy doctor-turned-medical missionary named Tom Dooley. Dooley wrote and spoke of Vietnam in terms of savage communists versus persecuted Catholics. He was a Catholic product of Notre Dame (although he never graduated), and he toured many colleges in the U.S. pleading his cause, which we now know was exaggerated and controlled by the CIA. College girls, in their knee socks and saddle shoes, loved the good-looking, eloquent Dooley. They did not know he did not fancy girls.

Dooley’s influence, largely forgotten today, was strong. He had a powerful friend in New York, Francis Cardinal Spellman, who in turn was close to the Kennedys and other prominent American Catholic families. Working with the CIA, he managed to seed our Vietnam involvement with the first of the distortions that would characterize our government line for the next 15 years. He made an anti-colonial nationalist movement seem to be a communist assault on western values, including the Catholic church.

Dooley did not live to see the results of his work. He died at 34 in 1961, at a time when the U.S. was barely involved in Vietnam. President Kennedy was much more focused on a nearer problem: Cuba. But we now know that even as he sent military aid, JFK was wary of a larger U.S. involvement in what he perceived as part of an anti-colonial movement that had swept Southeast Asia since World War II.

Initially, most Americans, myself included, supported U.S. policy. We were all brainwashed. I was also in the military, sort of. I had been commissioned through ROTC in the late 1950s at a time when the Army had too many junior officers and no war for them to fight. Many of us were given six months active duty and eight years in the reserves. Although trained in artillery, I was in a civil affairs unit. Our job would be to rebuild cities after we destroyed them. We were a wonderful group of screw offs, useless in peacetime. I wrote stories about our annual summer camps with titles such as “The General’s Martini,” “The Night We Boiled the Major” and “Can’t Anybody Here Hit That Deer?” We had so much fun that nobody ever quit our outfit.

Still, we would have made an effective active duty unit. We were heavy with brass. Our commanding officer was a state senator and we had abundant political connections, with lawyers, doctors, stock brokers, a Mercedes-Benz dealer, a college professor, a du Pont engineer, a labor relations specialist, service station owners and two journalists who would wind up in the magazine business together in Florida. Some of the older guys had combat experience in Korea. We thought Vietnam could use our myriad talents in pacifying all those Viet Cong villages. The army thought otherwise. When the war was getting hottest, they threw our whole unit out of the army. But my reserve obligation was up by then.

I had left sports writing for the real world, and in the next few years wrote about the growing war, even as my opinions subtly shifted. “War Boom” was a column about the Boeing Vertol plant near Chester, Pennsylvania, that was building the big Chinook helicopters still used today. One day a proud father came to the newspaper with his son who was a devout Christian and was joining the army despite all the noise being made by un-patriots whose protests were growing every year. The kid was no John Wayne; he seemed on the frail side and not intellectually gifted, but I wrote that the father wanted the world to know that his boy was doing his duty. Only years later did I learn the kid had been killed in Vietnam.

By then I was at Philadelphia magazine, where I went to Toronto on a story called “The Exiles” about local young men who had left the country to avoid the draft. Another piece, “A Welcome to Arms,” described the induction center where dozens of fresh-faced draftees gathered to begin their journeys to boot camp at Fort Jackson, South Carolina. I also did a piece about the status of our military reserves, which ranged from screw off units such as ours, to Air Force reservists who left jobs on a Friday afternoon, flew giant transports 8,000 miles to Nam, and were back in the office Monday morning.

By 1967 it was clear that most Americans were barely touched by a war that was affecting more and more families in a terrible way. We decided to do a short moody piece on the caskets coming home from the war. It turned out they did not come to the Philadelphia airport, but rather to the Air Force base at Dover, Delaware. The idea enlarged to covering a Vietnam funeral. We checked the papers for the daily casualty reports. After being coldly rejected by the first few families we called, we found a father who seemed to think he had an obligation to accommodate the media. And it turned out, the dead soldier was a friend of the younger brother of one of my college buddies. He and a dozen friends had enlisted together in various services. Four of them got to Vietnam and three came home without a scratch. The fourth, Pvt. Leonard Martin Jr. was killed in a mortar attack at an artillery post called Gio Linh.

We followed the process all the way from sitting in on the instructions they gave at Dover Air Force base to “escorts”—the soldiers assigned to accompany the casket to the funeral. They were told to be respectful and not tell any war stories. You were not there. Keep your mouth shut. Lenny Martin’s escort was a kid from Kansas. He did a great job.

The remains were delayed returning from Vietnam. We hung around, waiting with the family for a week. The magazine was mostly printed by the time of the funeral. It had not seemed a terribly sad event until that afternoon when people, many of them young, who had all seemed stoic, suddenly broke down en masse when the honor guard, including several of the friends who had enlisted with Lenny Martin, fired the 21-gun salute, and the young escort from Kansas presented the carefully folded flag to Martin’s mother with the reverent words “On behalf of a grateful nation.” It had been drizzling all day, but as the mourners returned to their cars to leave and the gravediggers began to lower the casket, the sun suddenly burst forth and the gray day turned freshly green and reborn.

“Back From Vietnam” was a first of its kind. Philadelphia magazine had a dramatic flag draped casket on its cover. Within weeks, publications around the country were covering Vietnam funerals. A war, which had for years seemed as distant as the names Tom Dooley and Indochina, had finally come home.

We visited the Vietnam Memorial Wall to make sure Lenny Martin was on it. He was, along with 58,318 others, most of who were barely born when Tom Dooley first made his misguided case in the 1950s.

There is one other name that should be added to that memorial. John F. Kennedy. There are numerous testaments by sources close to JFK that he thought Vietnam was a losing proposition and intended to withdraw American forces after the election of 1964, an election he did not live to see. Few recall that Kennedy had seen Vietnam first hand as a young congressman. In 1951 he visited the country and came home convinced that “in Indochina we have allied ourselves to the desperate effort of a French regime to hang onto the remnants of empire…”

JFK, his distrust of the CIA growing from the 1961 Bay of Pigs disaster until his murder in 1963, also sought to ease tensions with the Soviet Union over Cuba. Elements of our government, including powerful military and industrial figures, wanted just the opposite. They wanted, and eventually got, a bigger war in Vietnam. Some were willing to risk a nuclear war at a time when we could still win it. They saw President Kennedy as a traitor.

There is a growing body of opinion, of which this writer is a committed advocate, that it cost JFK his life. He is every bit as much a war casualty as those 58,318 names etched on that cold black granite memorial.

Image via

Now that the storm is over it is time to return to priority items, namely rewriting American history.

Aside from the fact that so much of it is plain silly, the disturbing fact about the controversy over Confederate memorials is that much of what has been written and broadcast reflects a one-sided understanding of that cataclysmic event in American history—the Civil War.

It has bothered us almost since it happened that the murder of President Kennedy in 1963 appears to be going down in history as the work of a lone nut, whereas the evidence is mounting that JFK was killed by a conspiracy involving the highest levels of our government. However, as new information surfaces year by year, there remains a chance that the truth may prevail.

Which makes the Civil War situation more troubling. The history of that conflict has long been written; the economic causes of the conflict and motives of the combatants should not be in dispute 150 years later. And yet they are. You see Robert E. Lee, one of the most admirable men in our history, is described as a “traitor.” And southern generals, and by extension all the poor grunts who fought and died under them, are said to have fought to preserve slavery.

Even reporters covering various memorial protests seem weak on the details of the Civil War. The Miami Herald, in its front page report of the latest Hollywood street debate, described John Bell Hood, one of the Confederate generals who has a street named after him, as “a commander at Gettysburg.” Technically correct. Hood, serving under James Longstreet, was one of nine division commanders in Robert E. Lee’s army. Hood had good reason to remember Gettysburg. He lost the use of an arm there. Transferred to the western theater, he lost a leg at Chickamauga. But history remembers him for a more significant loss. He took over command from Gen. Joseph Johnston of the Confederate army defending Atlanta in 1864. As bold as Johnston was cautious, Hood made some rash decisions. They led to the loss of his entire command, the only force standing in the way of Sherman’s infamous “March to the Sea.”

That’s just a mini example of shallow reporting on this subject. The main problem is that much of the public accepts the idea that southern generals and their men fought to enslave other men. Some historians cite the fact that southern state legislatures, in voting to secede, cited slavery as a reason. But those legislatures, dominated then as today by commercial interests, did not fight the battles and die in great numbers. Those common soldiers fought for their states, right or wrong, and considered themselves patriots rather than traitors.

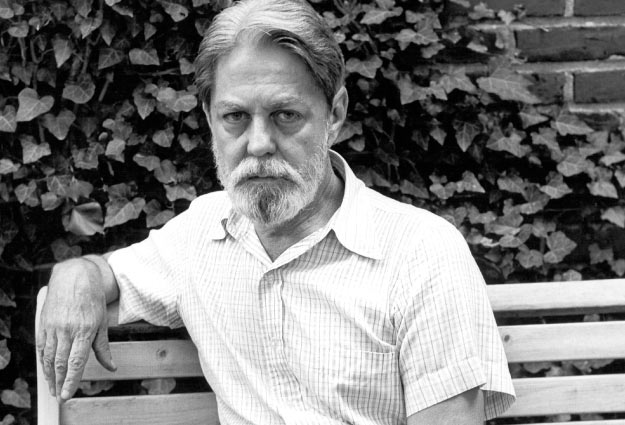

Shelby Foote, (pictured above) who spent 20 years of his life writing a great three-volume history of the Civil War, has put the matter in perspective:

“People who say that slavery had nothing to do with the war are just as wrong as people who say slavery had everything to do with the war. That was a very complicated civic thing.” In the same interview, Foote added in his infectious Mississippi drawl: “Believe me, no soldier on either side gave a damn about the slaves. They were fightin’ for other reasons entirely in their minds. Southerners thought they were fightin’ the second American revolution. Northerners thought they were fightin’ to hold the union together. And that held true throughout the whole war.”

Southern military leaders were considered anything but traitors in their own land. Just the opposite. Gen. George Thomas was shunned by his own Virginia family because he was the rare southern-bred officer who stayed with the union. Gen. John Pemberton was born in Philadelphia, but married a southern woman and served much time in the south. His two brothers fought for the Union and he was a pariah when he moved back to Philadelphia after he had held high rank in the Confederate army.

It is understandable that years after it ended, the south honored men it regarded as heroes. The same held true for the north. Monuments to southern generals were no more endorsements of slavery than monuments to northern men were considered thanks for freeing the slaves.

Some of the very generals whose history is being removed understood this better than anyone. The Union’s Ulysses Grant and Confederate James Longstreet served together before the war and remained friends afterward. Robert E. Lee had a cordial relationship with George Meade, the man who beat him at Gettysburg. A full quarter of a century after the war ended, Confederate Joseph Johnston died of pneumonia contracted when he stood outside on a cold February day while serving as a pallbearer at the New York City funeral of his old adversary, William Tecumseh Sherman.

That was the reality of the time. The monument destroyers should remember that—as if they knew it in the first place.

Image via

Thanks to the tragic weekend in Charlottesville, Virginia, the movement to rid America of the Civil War has been thus far nobly advanced. We seem poised to get rid of the streets named after Confederate generals in Hollywood, and now citizens have taken it upon themselves to pull down statues or deface Confederate memorials wherever they can find them.

Others ask, ‘Where will it end?’ ‘Will George Washington and Thomas Jefferson, who owned slaves, both suffer the fate of Robert E. Lee, whose memorials are in danger?’ ‘Will respected academic institutions bearing their names be renamed to avoid controversy?’ We certainly hope so. We personally are starting a campaign to rename Jackson, Mississippi, because it bears the name of Confederate Gen. Thomas (Stonewall) Jackson. WAIT! You say it wasn’t named for Stonewall Jackson? Rather Andrew Jackson? What difference does it make? Most people don’t know that, especially those foaming to change historic names, and some people who can’t spell the word history might be offended by the name.

Same for Jacksonville, Florida. You can’t take a chance that people may not realize that Andrew Jackson and Stonewall Jackson are not the same man. And who can doubt that if he had been a general in the Civil War, instead of the War of 1812, Andrew Jackson, a southerner, would have been on the southern side? He would join almost every other general—north and south—who stayed with their native states. Besides, just calling it “Ville” (pronounced vil, not vil-lay) will save money in typesetting.

The charge is on, cannon to left of us, cannon to right, and we are desperately looking for a Civil War memorial to eliminate that nobody has thought of yet. It is almost impossible to do in the south, for statue historian wannabes have added to the narrative by noting that many statues were erected around 1900, coinciding with the rise of the Jim Crow movement. Thus, they must be deliberate efforts by racists to lend nobility to the lost cause to preserve slavery. Thus, they must go.

That appears to be a sound argument until you realize that Civil War memorials appeared in the north at the same time. The fact is that it took several decades for some reputations to be validated by historians and survivors of the war, and even longer to find funds to memorialize prominent figures. In Washington, most of the famous memorials came around 1900 or later. Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman’s statue was dedicated in 1903, and Gen. Phil Sheridan rose in 1908. The Grand Army of the Republic Memorial was 1909. The massive Lincoln Memorial was not dedicated until 1922, the Dupont Circle Fountain in 1921 and the Ulysses S. Grant Memorial in 1924.

Elsewhere it was the same. Grant’s Tomb in New York was dedicated in 1897. In Boston, the famous tribute to Massachusetts’ valiant black soldiers—Robert Gould Shaw and 54th Regiment Memorial—across from the State House, came in 1897. Philadelphia’s elaborate Smith Memorial Arch was not completed until 1912. So much for the questionable timing argument.

That said, historical revisionists are claiming control over all the obvious southern memorials. We had to go north to find one whose disappearance we might be first to endorse. Begorrah, we found one! And it is no less conspicuous place than Gettysburg, the scene of the bloodiest three days of the war. There is a memorial there, hard by the Devil’s Den, honoring the famous Irish Brigade. That unit consisted of three New York regiments, including the legendary “Fighting 69th” and one each from Massachusetts and Pennsylvania. It suffered terrible casualties at the bloodbaths of Antietam and Fredericksburg late in 1862, and barely six months later, its thin remnants got shot up again at Gettysburg. It entered the battle only 500 strong and lost one-third of its men on the second day. By the end of the war, including replacements, it had lost more men than the 3,000 it mustered at the beginning.

It also had one of the most famous clergymen of the war, Father William Corby, whose 1910 statue blessing the Irish Brigade before battle is among the more conspicuous monuments on that monument-crazed battlefield. There is also a replica of the statue (1911) of Father Corby, arm raised in absolution, on the campus at Notre Dame, where he served as president after the war. At ND the statue is nicknamed “Fair Catch Corby.”

But we are not speaking here of that memorial. The one we want removed is the Irish Brigade memorial (above) that sits at the point where the brigade fought so heroically to slow the Confederate advance on the second day of that fight. It is one of the most striking monuments at Gettysburg—a Celtic cross almost 20 feet high, with an Irish Wolfhound (a virtually extinct breed) reposing at its base. Because it represents the valor of Irishmen, mostly immigrants from the famine era, who fought for the North (a good many fought with distinction for the South as well) we had to search the history books to come up with a reason to censor it.

One reason is that neither of our two Gallagher ancestors, our great grandmother’s brothers, John and James, who died in the Civil War, were members of that famous unit. In fact, we don’t even know what units they were with. There are 70 John Gallaghers and 35 James Gallaghers from Pennsylvania listed in the history of the Pennsylvania Volunteers. We think they both came from around Easton, Pennyslvania, but regiments from that area were mostly square heads. (That is a term of respect for Germans.) Anyway, our boys were not part of the Irish Brigade, so that’s one strike against it.

But our real reason for picking on this particular memorial is the fellow who designed it. His name is William R. O’Donovan. He was a self-taught sculptor who worked in New York and was famous for war memorials. Great Irish name, O’Donovan. So far, so good. But history has forgotten that before he became known in New York, he was born in Virginia. He was only 17 when the war began, and like Robert E. Lee, he fought for his native state. THE BLOODY MICK WAS A FREAKIN’ REB!

Obviously, this young fellow was a flaming racist. He went to war, not because everybody in his neighborhood did, and you were considered a traitor if you did not, but because he believed in slavery and was willing to die to preserve it. Forget that he lived most of his life in New York and sculpted a moving tribute to his fellow Irishmen who fought on the other side.

We modern historical revisionists have the ability to see only what we want to see, and we are in a desperate fight to be the first to find another monument to remove. So honor our claim to the Gettysburg Irish Brigade memorial. Just one word of caution: Before you try to pull it down, make bloody sure no Irishmen are watching.

Image via

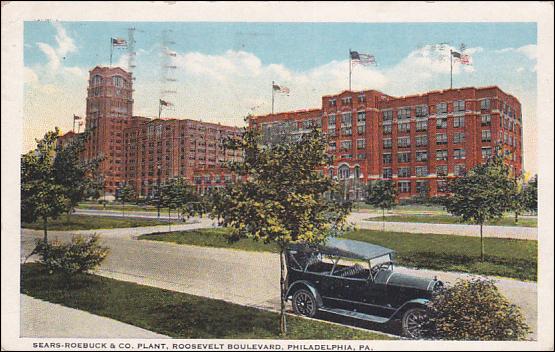

The business pages recently have carried stories about what appears to be the slow expiration of Sears. Some reports describe the demise of the once iconic retailer as almost a death in the family. For our family, that is close to home. Both parents worked for what was then called Sears, Roebuck & Co. in Philadelphia. In fact, that’s where they met.

Richard Sears, who sold watches in his spare time working at a desk job in a railroad station, founded Sears in the late 1800s in the Midwest. He soon sold everything else, and much of it far from his Chicago base. In Philadelphia, Sears once had a huge presence. It had an enormous building off Roosevelt Boulevard, which is U.S. Highway 1 in that city. It looked more like an aircraft factory than an office building and had a 14-story clock tower. It was built as an outlet store and plant when Sears was in its heyday with a mail order business that foreshadowed today’s Amazon operation.

The building (above) opened in 1920, and dad and mother went to work there soon after. They were among the first of thousands employed at that site for 70 years. Dad apparently worked in plumbing and heating from his earliest days with the company. Today you would add air conditioning to that field. Mother, just out of high school, was with an advertising unit. One of her tasks was translating letters from French. And she could barely read French. Our parents’ closest friendships were made there, and numerous of our boyhood friends had relatives in the Sears family. It was a great place to work, very progressive for its time. It had a profit sharing program, which enabled many employees of that era to retire with small fortunes in Sears stock.

The Depression, so hard on many families, was barely felt by our family. Dad, who never finished high school, moved up the Sears management ladder and in the 1930s was transferred to Port Newark, New Jersey, where Sears had one of its production facilities for its Modern Homes division. It had started in the prefabricated housing business at the turn of the century and sold 70,000 houses in many designs, some of them pretty fancy. They were built in two plants (the one in Port Newark took up 40 acres) and shipped the raw material for houses by rail around the country, where local carpenters put them together. More than a few were constructed by their owners. Those houses today are prized. People actually search the country to see them. Dad’s background with Sears suggests he handled the plumbing aspect of the home building operation. Buyers could pick their kitchen and bathroom designs; it all came with the package.

Dad started when the Modern Homes unit was strong in the late 1920s. He commuted to North Jersey from Philadelphia for several years, then married and moved our family to North Caldwell, New Jersey. It was just in time to see the Depression catch up with the housing market. Home building slowed and Sears decided to shut down its modular home unit. Dad managed to stay with Sears, but in 1939 it entailed a move to Elmira, New York, where he managed that store’s plumbing and heating department. I gather he did well. I recall mother took us outside to see if we could catch a glimpse of his airplane flying overhead to Washington, D.C. where he received some kind of company award.

Elmira was a pleasant little town, famous as one of Mark Twain's haunts, but mother missed her big family in Philadelphia. We lived near the Chemung River, which had a habit of flooding. Two exciting things happened in the three years we lived there. At age 4 a horse nearly rolled over on me because I was so small the beast did not know anyone was on him. That ended my equestrian lessons in a hurry. The other event was war. The country was still in shock from Pearl Harbor at the beginning of 1942 when dad managed to engineer a transfer back to the big facility on Roosevelt Boulevard—and almost immediately got fired.

As he told the story, Sears calculated that the war would kill its retail business, and decided to cut back on middle management. As it turned out, so many men entered the service that workers were in short supply. Thousands of women filled their jobs.

Dad said the man tasked with firing people was a fellow he had known years before.

“I didn’t like him and never took pains to conceal it,” dad said later in life. “It cost me my job.” He was 46 years old with three young kids and a new mortgage, and after 21 years with Sears, he was on the street. Unfortunately, he had not taken advantage of Sears’ attractive profit sharing program, so he had little backup. A recent article quoted a manager at a Sears store in Georgia who lost his job when his store closed: “But after working there all of those years and then losing my job, it hurts. I’ve taken a big emotional hit from this.”

That statement could have come from dad. Photos of him from the 1930s show a jaunty, almost cocky looking guy in a derby hat. But after losing his job, pictures show a more subdued, resigned man. He managed to get work with a big insurance company and stayed with them until he retired. He knew the value of life insurance; he just didn’t enjoy selling it. When I was 19 he suggested I get a little policy, but then called in one of the young men in his office to write it up.

Our family never took it out on Sears. Over the years we bought appliances from our local store and what little hardware we needed. And their post-Christmas sales were a good way to pick up toy trains at a big discount. Sears did a major catalog business. Even the houses they built could be ordered by mail. But our only experience with it was memorable, and not in a good way.

Our first year in Florida we ordered Christmas presents for the kids through the catalog. My wife had thoughtfully chosen a bunch of stuff, and it was all supposed to arrive a few days before Christmas. For reasons still unknown, it did not. Christmas Eve found us in Smith’s Drugs, which used to be in Fort Lauderdale’s Gateway Shopping Center, trying to get something, anything, for three small kids. Smith’s was a surprisingly well-stocked store, and within an hour we had all sorts of items, from toys to stocking stuffers. The kids never knew the difference. But maybe we should have sensed it was the beginning of the end for Sears.

Over the next decades, Sears remained the obvious first choice for many things. We got tools on a regular basis and a variety of household items, but one by one things you used to find began to disappear, along with other customers. The last major purchase was a refrigerator, but that was at least 15 years ago. We still used their auto store for tires and repairs, but had no need for much else. There were no trains on sale after Christmas.

It is ironic that a company, which invented the mail order business, is among the many retailers being undercut by the modern application of the same idea. It is further ironic that a company that started selling watches still has at least one local customer that likes its inexpensive wristwatch bands. We buy one every couple of years. That probably won’t keep Sears afloat.

Image via

We have commented previously on the effort to change three street names in Hollywood from those of prominent Confederate generals. It’s a problematic idea and reflects a general misunderstanding of the complexities of the Civil War. That bloody conflict was rooted in the birth of the country—an ongoing debate over the supremacy of a federal government over individual states.

Slavery was the economic cause of the war. Without it, there would have been no friction worthy of 600,000 deaths. But there was also a political cause, for which most men fought, and this is what those opposed to Confederate monuments don’t seem to get. The Southern states did not think Northern states should tell them what to do. And with few exceptions, soldiers went to war for their neighborhoods.

Historians regard one of the generals, Robert E. Lee, as a great American. Like almost every prominent officer and enlisted man, he fought for his state. His gracious acceptance of defeat and subsequent reunification of the states helped ease the bitterness of the loss among Southerners.

Few historians would deny that had they been alive during the Civil War, such honored men as Patrick Henry and Thomas Jefferson would have been on the Southern side. Probably even George Washington. Proud Virginians all.

The other disputed streets are named after John Bell Hood and Nathan Bedford Forrest, both prominent Southern military leaders. Hood was a very brave and aggressive soldier who gave half his body (an arm and most of a leg) to Confederate service. Unlike the others, he was not a gifted general, but he also had more than his share of bad luck.

Forrest was a brilliant commander. Historian Shelby Foote wrote that he and Abraham Lincoln were the two geniuses produced by the war. The knock on him is that he was a pre-war slave dealer, and helped start the Ku Klux Klan, as a political movement to combat the excesses of the Reconstruction Era. What is often ignored is that he also turned against the Klan just a few years later when it became too violent. He helped shut it down. Still, he is the one man whose legacy is understandably tarnished.

Anyway, the war to rename the streets goes on. The consensus seems to be that, even among those who think the whole thing is rather silly, if it gives offense to people, let the changes occur. But it is getting to be an economic battle. Residents of the three streets are complaining about all the work they will need to do to change their addresses on driver’s licenses and other documents. It is possible their mail will be misdelivered for the rest of their lives. Hollywood officials estimate the cost of the name changes at more than $22,000.

A few weeks ago, the Sun-Sentinel quoted one such resident who did not want to go to the trouble of changing personal documents:

“What bothers me is that people who don’t live on the street and don’t even live in Hollywood are getting involved. What do they care? It’s not going to impact them at all.”

Ironically, that’s similar to the attitude Southerners had toward the North during the Civil War.

Because we do not live on the aforementioned streets, we accept this neighbor’s kind invitation to butt into this conversation with a modest proposal. Instead of spending $22,000 to rename the streets, how about spending almost nothing to rename the people they are named after? Simply put in the record, as we are doing right now, that Lee Street is named for Spike Lee. We don’t know everything about that distinguished fellow, but we are confident that he or his ancestors were not officers in the Confederate Army.

Forrest Street could be retro-named after that universal American hero—Forrest Gump. Although Mr. Gump was from Alabama, his gentle and loving nature reflects the national desire to bring people together again, so helpful in these divided times.

He was also a bit on the simple-minded side, a secondary tribute to the folks pushing for the name changes.

As for Hood Street, there are options. It could be named after Robin Hood, who stole from the rich and gave to the poor, which should be a popular sentiment in that part of Hollywood. To broaden the tribute, why not name it generically, after all the hoods in the world. That is an umbrella expression, which has changed over the years. In Philadelphia in the 1950s, it was applied to young men of culturally inadequate backgrounds and was sometimes applicable to women as well. In basic terms, it meant the opposite of preppy. There are probably a few representatives of that genre living in Hollywood right now.

Having just saved the city of Hollywood $22,000 in cash and untold amounts in aggravation, we ask nothing in return except to have a street named after a Gen. McCormick. Alas, there were no Gen. McCormicks in the Civil War. We would settle for mother’s name; there was a Union general, and a pretty good one, named Sweeney. A Cork man; we would have preferred he be from Donegal. Either way, he should provoke no ire. Now, just find that lucky street.

Image via

You can see it now. Motorist I, in heavy downtown traffic, is late for a meeting with the boss. Motorist I sees the unprintable streetcar blocking his lane of traffic half a block away. He veers sharply to the left, hoping Motorist II in that lane will let him in. But Motorist II is one of those angry types who does not ever let anybody get in front him. To do so would be an affront to his manhood. He accelerates and hits Motorist I, who is now truly late to see the boss.

Motorist II is out of the car, screaming at Motorist I. Motorist I senses a foreign accent in Motorist II and calls him an unprintable racial slur. Motorist II understands enough English to be offended and makes a threatening gesture, and Motorist I, citing Florida’s “stand-your-ground law” reaches into his car for his Glock. Too late. Motorist II crouches and gets his .25 caliber Beretta out of his ankle holster and shoots Motorist I in the groin before the latter can even aim.

Staggering back in pain, Motorist I fires. He misses Motorist II but the bullet hits a pregnant woman coming out of a building across the street. Motorist II, getting over his road rage when he realizes the incident might lead to his deportation, runs to his car and tries to flee. But he can’t move in traffic because the streetcar coming the other way has everybody blocked. Panicking, he takes off on foot.

Suddenly thinking like a lawyer, he throws his gun away, aiming for a trash basket across the street. Under the stress of the situation, he forgets to bend his knees as on the foul line in his native Montenegro and hits the aerial of a car. As the weapon falls to the street, the impact causes it to fire, and the bullet goes up in the air and strikes a traffic helicopter rushing to report the scene. Unfortunately, it hits the chopper pilot, who loses control. The chopper plunges down and strikes the streetcar that started all the trouble. There is a fiery explosion. Fortunately, the trolley car is as usual almost empty, and only four people die. Unfortunately, none are attorneys.

OK, that series of events is not likely. Such things only happen in television ads. But it is not unthinkable that a streetcar blocking traffic could lead to some inappropriate decisions by motorists stuck behind it. And that would be the least of the problems associated with the proposed WAVE Streetcar in downtown Fort Lauderdale.

The real problem is that the proposed streetcar is a very expensive idea designed to help the rapidly worsening Fort Lauderdale traffic situation, but it more likely will just make things worse. Public opinion has been building against the idea, and Fort Lauderdale Commissioners are increasingly conflicted. Mayor Jack Seiler has pointed out the problems. Let’s hope his colleagues listen and wave off the WAVE.

This is not a bias against streetcars. We actually like them. Growing up in Philadelphia, we lived on a cobblestoned avenue that had two streetcar lines. They rattled in our dreams. Even as the original concept of sharing lanes with other traffic has been long abandoned around the country, streetcars still survive with the right concept. Where they are useful are new systems that provide dedicated lanes in congested downtown settings, combined with newly constructed tracks reaching out to suburban locations and high-traffic destinations such as airports.

Denver is an excellent example. Its electric vehicles have exclusive lanes (shown above). They move around faster than cars in the downtown, and then connect to existing railroads, or new rights of way, to serve communities outside the city. The airport connection makes six stops on the 25-mile route. It takes 37 minutes.

Fort Lauderdale’s application would make sense if the streetcars had dedicated lanes. But they won’t. Even the planned expansion to places such as the Davie education complex would share the road with cars and trucks. And it isn’t as if Fort Lauderdale has no alternative to reducing downtown traffic. More effective, infinitely cheaper and available without delay, would be the Chattanooga, Tennessee model. For decades a downtown shuttle has used small electric buses to solve the same problem as Fort Lauderdale faces. They are free in theory, although people can, and usually do, make a 25-cent contribution at a box at the main terminal at the railway station.

They produce no exhaust in a city with a serious air pollution problem, do not hold up traffic and are fun to ride. That idea is hardly new. Atlantic City has had its famous jitneys for a century. Like Chattanooga, they run so often that riders can almost always see one coming down the street. They also pass each other if they have no riders getting off. It is a popular and efficient system.

Fort Lauderdale’s problem seems to be a reluctance to back off after much time and planning has gone into the system. And apparently developers are pushing for it because it will ease parking requirements for their new (and traffic generating) high-rises, which only these developers seem to want.

Happily, Fort Lauderdale taxpayers seem to be getting the message—slowly. One hopes those in charge will do the same. Pray they have the good sense to WAVE it off.

Image via

If it is still running, and it probably will be, we plan to take the Auto Train later in the summer for maybe the 30th time. We don’t know the exact count, but we started using it in the early 1970s when it was launched as a private company. Amtrak did not take over until 1983. Since the 1990s, somebody in the family has ridden it every year; some years we took several trips, up and back. And not always in the summer. We took at least one round trip up for the Christmas holidays.

We obviously like the idea, and we have written about it a number of times, wondering why the concept has remained limited to just one route from central Florida to northern Virginia, close to Washington. It seems like an idea that would work on most of Amtrak’s long-distance routes.

In fact, the original Auto-Train Corporation did attempt to run a second train, after it began to make money on the initial route. It ran from its station in Sanford, northeast of Orlando, to Louisville, Kentucky. The concept seemed sound, but its engines proved too heavy for the poorly maintained track on the old Louisville and Nashville Railroad. It had derailments, followed by lawsuits. The railroad had warned of the danger of the heavy engines. The poorly executed expansion put the original company out of business in 1981, and several years later Amtrak took over. The train has been a success. It was profitable for years, and may still be. If not, it doesn’t lose much money, at least not by Amtrak’s standards.

We revisit the subject in response to the new proposed Trump budget that would cancel many of Amtrak’s trains, including Auto Train and the two regular long-distance trains that serve Florida from the northeast. We propose, as we have before, that instead of eliminating those unprofitable, but still useful long-distance trains, Amtrak combine them with auto trains. This is not an original thought. The original private Auto-Train Corporation planned to do it years ago, combining its Midwest auto train with “The Floridian,” a regular train from Chicago to Miami. Veteran rail observers may recall seeing that train, pulled by distinctive brown and orange Illinois Central diesels, on what are now the CSX tracks along Interstate 95.

The first step would be to return to the Midwest, using the existing Sanford facility to run an auto train not just to Louisville, but closer to the big Chicago market. In addition to carrying people and their cars, it would also carry carless passengers. To keep it fast (Auto Train often runs ahead of schedule) the stops would be only at major markets. Current Amtrak trains serve many small towns, but this idea would stop at only busier destinations. En route to a terminal south of Chicago, (Lafayette, Indiana seems about right) you could stop at Jacksonville, Macon, Atlanta, Chattanooga, Nashville, Louisville and Indianapolis. At 10 minutes per stop, that might add an hour or two to the trip. But so what, people on a train are not in a big hurry.

Initially, the train need not be daily. Again, train riders are not in a hurry. As traffic grows, the schedule could increase. A super terminal not too far south of Chicago could then serve as the starting point for most of Amtrak’s current long-distance trains. Five established Amtrak routes leave the Chicago area for the south and west coast. All those routes are longer than the current Auto Train (855 miles). The California Zephyr, from Chicago to near San Francisco, covers more than 2,000 miles, much of it through the spectacular Rockies and the Sierra Nevada mountains. Its 30 plus station stops could be cut in half, but include the population centers of Omaha, Lincoln, Denver, Salt Lake City, Las Vegas, Reno and Sacramento, along with a few of the more scenic vacation spots along the way. The trip currently takes a little more than two days. A few extra hours would hardly affect ridership.

On those long routes there would be the opportunity to add facilities to load and unload vehicles at least once. It is surprising how fast Amtrak crews (shown above) can do that right now. It would not appreciably delay the train and greatly add to its usefulness.

Ultimately we could see the idea working on the shorter eastern routes, using the Lorton, Virginia Auto Train terminal as a starting point for cross country auto trains along existing Amtrak routes to New Orleans and Chicago.

Would these hybrid trains make money? Probably not, but they surely would lose a lot less than they do now and likely cease the clamor to destroy a valuable national asset.

Image via