In the wake of last week’s tragedy at the airport, it seems banal to write about a wake for an Irish pub. But anyone passing Maguires Hill 16 on Andrews Avenue in Fort Lauderdale last week knew that something unusual was in the air. From the announcement last Monday that the well-known restaurant/bar had been sold and was closing, the parking lot and any available space nearby were jammed by people stopping by to say farewell to a local institution.

There was quite a lot written about the closing—about the surprise—despite the fact that rumors of a sale had been circulating for months. Yet nobody expected that new owners would close down a site with a 50-year history on such short notice. Also missing from news reports is the most compelling part of that history—how a location in a once somewhat seedy, off-the-beaten-trail location, which had been a redneck hangout frequented by bikers, became an iconic entertainment location with an extraordinarily broad following.

That story dates to 1989. The bar was then known as Fridays Downtown, but you wouldn’t confuse it with the trendy TGI Friday’s chain we know today. Alan Craig had a car restoration business on a nearby street, and he used to bring his workers in for happy hour. Craig was also a musician and singer. Back in Dublin, he had participated in what the Irish call “sessions,” where amateur musicians got together in pubs on weekend nights.

“One night I brought the guys in and somebody had a guitar, and I played some Irish songs,” Craig recalled Monday. “The owner said, ‘Why don’t you put together an Irish night on a Friday night?’ Nobody was in there after nine o’clock. It was a ghost town. So I did. It was an Irish night, just for fun. Nobody got paid. In a few weeks, we had 50 people there, and then the next week 75. It just kept growing. And the owner says, ‘Why don’t you buy the place and turn it into an Irish pub?’”

Craig did, using the name of a Dublin landmark, but it was not totally to the liking of his then wife Hilary Joyalle, who had worked in the restaurant business in Ireland. But she soon changed her mind as week after week the crowds increased, and they began serving lunch and dinner, making the place as much a restaurant as a bar. The musical group enlarged. Craig teamed with Mick Meehan, another Irish native, and they put together the Irish Times, which became one of the best Irish bands in Florida, often doing gigs outside the bar. The music reputation spread beyond the state, even across the sea. Some of the top names in Irish music, groups such as The Commitments, performed at the pub.

The timing was perfect. The Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem had popularized traditional Irish music in the ‘60s and ‘70s, singing rebel and drinking songs largely unknown in the United States. They inspired Irish and American songwriters. When Alan Craig, with his gravely voice, sang “Fields of Athenry” it was a relatively new song by Pete St. John. Maguires’ audiences often requested the mournful ballad recalling the Irish famine era of the 1840s. It has since become a sports anthem in Ireland, sung at soccer games by the entire crowd.

Alan and Hilary went on to establish Irish bars in several other Florida towns. In 1999, they sold Maguires. The new owner owned it only briefly, selling to Jim and Martina Gregory, who owned bars in Ireland. They bought Maguires only after they were able to also acquire the real estate, including the large parking lot, which the Craigs had not owned. That ownership was central to their recent sale to a local group expected to develop high-rise buildings in the neighborhood, which is seeing extensive redevelopment. Far from the seedy days of old, it is within walking distance of the new All Aboard Florida train station, along streets lined with new apartments.

The Gregory family remodeled the place and expanded to outdoor seating. From its first days under the Craigs, it had attracted a journalism crowd. The former New Times office was just two blocks away, and the young staffers often gathered there. Over the years, courthouse types and law enforcement people—Broward Sheriff deputies, Fort Lauderdale police and even plain-clothes federal marshals—joined them. Political figures, including Fort Lauderdale Mayor Jack Seiler, often had lunch meetings. Musically, the entertainment became less Irish, but the food and décor remained old country. The burnished wood and walls crowded with photos from Ireland’s past made for an exceptionally cozy atmosphere, even by Irish pub standards.

The Gregorys also made it a popular sports bar. From its early days it had attracted European soccer and rugby fans, along with Gaelic football broadcasts, and the new owners enlarged its sporting footprint. Recent Sundays saw fans from the Pittsburgh Steelers and Baltimore Ravens gathering to root for their teams. The large local Notre Dame club met for Irish football, and Louisville brought in a crowd for both football and basketball games. Those fan bases are among the many saddened by the closing.

The former owners admired the new owners’ management. Says Hilary Joyalle, who for 13 years has owned The Field Irish Pub on Griffin Road in Dania Beach: “Jim and Martina didn’t do the Irish music as much, but they kept the spirit of the place very much alive.”

Surely to goodness, they did. And Monday, the day after the official closing, the normally crowded lunchtime parking lot was empty save for a few workers completing the shutdown operations. Above the Maguires sign the Irish and American flags were stirring in the chilly wind, and a sentimental soul might think he heard the raspy voice of Alan Craig awakening ghosts of the past.

Low lie the Fields of Athenry

Where once we watched the small free birds fly.

Our love was on the wing, we had dreams and songs to sing

It’s so lonely ‘round the Fields of Athenry.

Photo by Bernard McCormick

There are too many people named Ryan. It may be the most common name in the world if you consider it as both a last and, increasingly common, first name. It has to be in there with Kim and Muhammad, and they don’t count because they’re not Irish.

We take more than a passing interest in the over-Ryaning of America because we have the name in our family. Great grandmother Mary Ann Ryan was from Tipperary, where everybody is named Ryan. Hers is the most distinguished line in our detailed maternal family tree, in what is otherwise a typically no-account Irish history. Her father, born around 1816 in Thurles, County Tipperary, was allegedly an engineer—pretty rare for the Irish of his time. Not a train engineer, mind, but somebody who took part in the building of a bridge in Glasgow, Scotland, and was working on a construction project in St. Louis when he died.

More importantly, Mary Ann Ryan was said to be a cousin of Archbishop Patrick John Ryan of Philadelphia (by way of Thurles, Tipperary), who is considered one of the more important figures in the early Catholic Church in the U.S. Before he (shown above) came to Philadelphia in 1884, he ministered to Confederate prisoners in St. Louis. In Philadelphia, his charm and oratory helped ease tensions between the old-line Protestant power structure and the Irish immigrants. He has a nice high school named after him. Evidence of the blood relationship is strictly family lore. The Arch was allegedly an occasional dinner guest of grandfather Edward Sweeney, Mary Ann Ryan’s son-in-law, who published Catholic books in Philadelphia at the turn of the 19th century. It would make sense that they were friendly.

Back on topic. Ryan is a common name–ranked eighth in Ireland, so you would expect the name to travel. In America, we had financier Thomas Fortune Ryan in the colonial era, Father Abram Ryan (priest-poet of the Confederacy), actors Robert Ryan and Meg Ryan, and author Cornelius Ryan (The Longest Day). Making it into at least three movies—”Von Ryan’s Express,” “Ryan’s Daughter” and “Saving Private Ryan”—didn’t hurt the name’s popularity. There was also a long-running soap opera, “Ryan’s Hope.” Often forgotten is the fact that Charles Lindbergh’s plane, which flew to glory, was built by Ryan Airlines—one of several aviation companies founded by T. Claude Ryan. Aviation is in the Ryan genes. More recently in the old country, Tony Ryan (Thurles, Tipperary, of course) built Ryanair into a major player in European commercial aviation.

Sports reek with the name. Pitcher Nolan Ryan, quarterback Matt Ryan, runner Jim Ryun (a rare variation of the name), football coaches Buddy Ryan and Rex Ryan, basketball coach Bo Ryan, and Frank Ryan in several sports. There is a Ryan Center, home of the Rhode Island University’s basketball team—named for Thomas M. Ryan, a URI alum and former CEO of CVS.

Politics of late are infested with Ryans, beginning with House Speaker Paul Ryan, who may become our first Ryan president. There is also Congressman Tim Ryan of Ohio, who challenged Nancy Pelosi for Democratic Minority Leader. Locally, just in Broward County there are two prominent Ryans, County Commissioner Tim Ryan and Sunrise Mayor Michael Ryan.

On their own, there are plenty of Ryans. But the real problem started when people began using it as a first name. That is a fairly recent phenomenon and has spiraled out of control. Why Ryan? None of the apostles were named Ryan. Not a single signer of the Declaration of Independence was Ryan. Wikipedia says it began in the 1970s with the actor Ryan O’Neal.

And yet, Ryan is everywhere you turn today. It has been one of the most common boys names for two decades. First name Ryans are all over sports. In recent times there have been three pro quarterbacks—Ryan Tannehill, Ryan Fitzpatrick and Ryan Leaf. And it shows up in all games. Ryan Howard, Ryan Lochte, Ryan Braun, Ryan Callahan (hockey), Ryan Arcidiacono (Villanova).

Other common Irish surnames have become first names. Kelly and Neil are popular, Connor less so. But none rival Ryan. Why Irish more than other nationalities? The English version of Celtic names is short, for one thing. The old Celtic name was, among other tongue-twisting possibilities, O Riaghain. Shortened, Irish names have become very American sounding. You don’t find many people with the first name of Pelosi, Shula, Huizenga, Netanyahu or Arcidiacono.

The name is equally big in show biz. One website lists 16 Hollywood hunks named Ryan, among them Ryan Gosling and Ryan Reynolds. Ryan, with various spellings, has become a female name, not always to the delight of the namee. There are websites devoted to the name that identify it as a strong masculine name, which some women named Ryan say ruined their lives. The same website also has a number of comments that the name has become overused.

Our point exactly. But we must also point out that our clan, which came by the name the old fashioned way, subtly preserved its family legacy without contributing to the Ryan pollution. We have a grand nephew, John Ryan Grande. Isn’t that grand, as the Irish say.

Image via

Fake news has been much in the news. There have even been reports that some of the propaganda that people who voted for Trump swallowed ravenously were stories planted by Russia. Paul Horner, who makes a living doing fake news, also claims he got Trump elected.

“Honestly, people are definitely dumber,” he told The Washington Post. “Nobody fact-checks anything anymore—I mean, that’s how Trump got elected.” This is how so many people became convinced President Obama was not born in the U.S. and was a Muslim.

Although the term “fake news” may be new, the concept is not. It has long been used by countries in warfare. Winston Churchill said, “In wartime, truth is so precious that she should always be attended by a bodyguard of lies.” During the same World War II era, the Japanese people thought they were winning every battle until bombs began falling on their houses. They were not told when four of their aircraft carriers—the heart of their navy—were destroyed in a single battle at Midway, just six months after those same carriers devastated Pearl Harbor.

In normal times, however, major news organizations have generally agreed on basic facts, even if their editorial opinions varied. Alas, this is no longer true. Today, political parties, and media which favor them, cannot agree on facts. That was noted years ago when Sen. Daniel Patrick Moynihan warned that “everyone is entitled to his own opinion, but not to his own facts.”

That was just about the time that political operatives began doing exactly that. Convinced that the press was unfair, they began seeking new outlets for their own “facts” disguised as news. An early and glaring example was the 1968 presidential campaign, when Roger Ailes, then a young producer of “The Mike Douglas Show” in Philadelphia, convinced candidate Richard Nixon to let him manage the media aspect of his campaign.

He shielded Nixon from the mainstream press. Instead, Nixon appeared in a series of town hall meetings, which were packed with supporters asking questions arranged in advance, designed to make Nixon look as if he were candidly talking on tough issues, when really it was all clever propaganda. Joe McGinniss’ book The Selling of the President 1968 exposed all of this. That best-seller made Ailes and himself famous. It also set Ailes on a path to create his own media form that would report the news his way, but it took almost 30 years before cable expanded the media landscape and enabled him to launch Fox News.

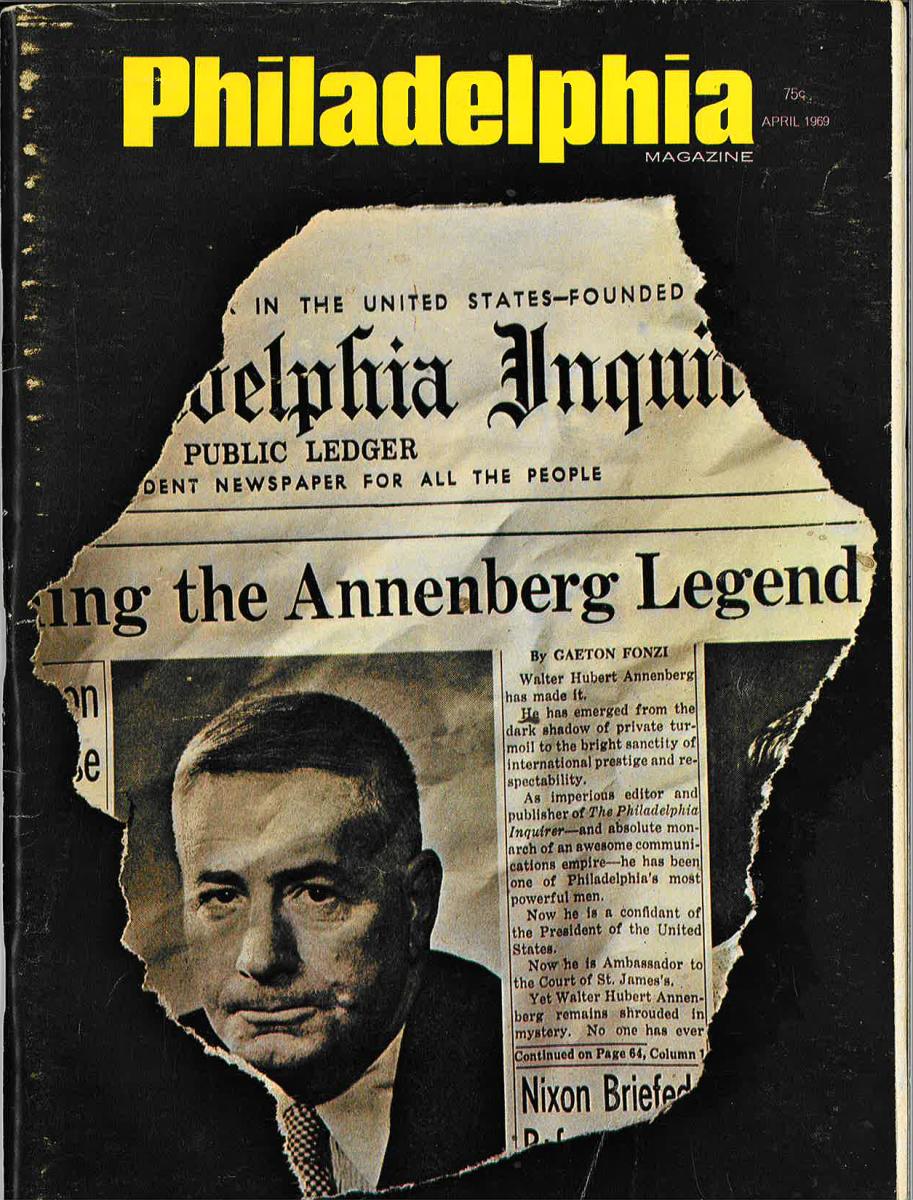

It was fitting that both Ailes and McGinniss were in Philadelphia at the time, for in the1960s the Philadelphia Inquirer, then owned by Walter Annenberg, was a corrupt operation. Annenberg blacklisted people he did not like. One was Milton Shapp, who ran for Pennsylvania governor. An Inquirer headline at the time read that Shapp had denied being in a mental institution. But nobody had said he was.

Annenberg also hated Matt McCloskey, who had owned the rival Philadelphia Daily News. McCloskey became ambassador to Ireland, but Annenberg never let his photo appear in the Inquirer. Then, at a political function, McCloskey managed to get himself in a photo taken for the Inquirer. He was between President Kennedy and Philadelphia Mayor Richardson Dilworth. He gleefully told people they could not keep him out of the paper. But the next day a gray blob appeared when the photo ran. McCloskey had been airbrushed out of the shot.

And when the Philadelphia Warriors moved to San Francisco, Annenberg was upset. A few years later, he suspected the Warriors’ old owner was behind the city’s new NBA team. He wasn’t, but for a period of time the 76ers got two paragraphs when they won, only one when they lost. Hard to believe? It happened.

Annenberg’s reputation for vindictiveness was so widely known that one of his pet employees took advantage of it. Harry Karafin was Annenberg’s hatchet man. When Karafin called, powerful people shuddered. For several years Karafin ran a shakedown scheme, threatening investigative stories, while a public relations accomplice suggested the potential target could use some PR advice. Karafin did not run fake stories; he faked running them. Among those who paid thousands in his extortion scheme was Philadelphia’s largest bank. Karafin was eventually exposed by Philadelphia magazine. He died in jail.

The co-writer of that story, our late Gold Coast magazine partner Gaeton Fonzi, later wrote magazine articles (above) and followed up with a book on Annenberg, detailing his decades of abuse of power. Shortly thereafter, Annenberg sold the paper to Knight-Ridder, at the time owner of the Miami Herald. The new ownership turned it into one of the best papers in the country, winning 19 Pulitzer Prizes over ensuing decades.

Today the purveyors of fake news do not go to jail. But they should.

Image via Philadelphia magazine

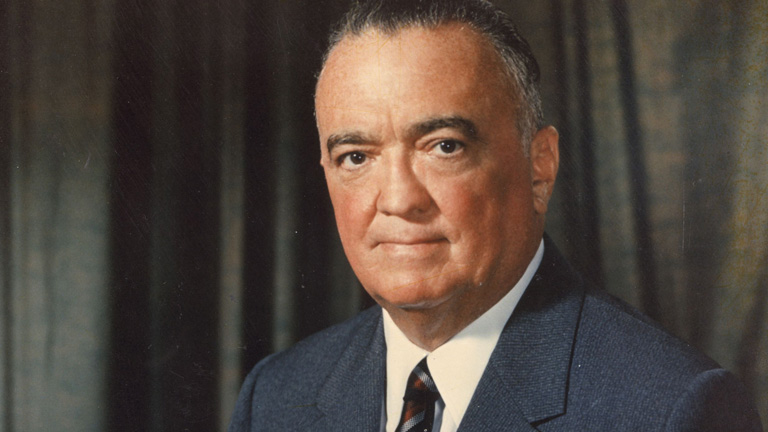

The behavior of FBI Director James Comey, which seems to have had an effect on the recent election, has been described as a low point in the history of that esteemed organization. Hardly. Does no one remember J. Edgar Hoover? Maybe not. Recently, in a conversation with a young college grad (not a deplorable), the name Grace Kelly came up. The young person had no idea who she was.

Hoover, of course, was the legendary founder of the FBI and its director for more than 35 years. An iconic figure in his lifetime, it has since been revealed that he abused his office in a number of ways, including keeping blackmail material on people—even presidents. To put the recent bad publicity in perspective, it has also become known that his FBI participated in one of the most disgraceful episodes of the 20th century—the cover-up of the murder of President John F. Kennedy.

Hoover decided almost immediately after the murder that Lee Harvey Oswald had acted alone. His bureau did the investigative work for the Warren Commission, which merely interviewed witnesses sent to it by the bureau, and relied on the information supplied by FBI. Those witnesses and details were screened by the FBI to exclude the considerable body of evidence pointing to a conspiracy, in which Oswald’s role was to take the hit, literally, for the crime. The Warren Commission ignored some FBI information, which contradicted that conclusion.

None of this was known in 1965, of course. When the Warren Commission issued its report, very few doubted it. But over the years, up to this day, researchers with access to slowly declassified information have convinced most of the country that there was a conspiracy. If the awful crime did not involve our own government, then surely the cover-up did.

We now know that Oswald was hardly a lone nut as the Warren Commission termed him. In the words of the late Pennsylvania Sen. Richard Schweiker, who reopened the investigation into the assassination in the 1970s, Oswald had “the fingerprints of intelligence all over him.” Gaeton Fonzi, a partner in Gold Coast magazine at the time, was hired to look into possible Oswald’s connections to the anti-Castro movement in Florida.

Fonzi spent five years on the government payroll and concluded that even the second investigation was rigged. He exposed the charade in his book, The Last Investigation, which first appeared in Gold Coast as two long articles in 1970. Upon his death four years ago, The New York Times called Fonzi's book one of the best on the assassination. Fonzi, and other investigators following up on his pioneering work, found evidence that Oswald had both CIA and FBI connections, and the latter must have been known to J. Edgar Hoover at the time of the assassination. He also probably knew that Jack Ruby, the man who murdered Oswald in the days after JFK’s death, had organized crime connections, and he also should have known that Ruby was part of the CIA’s anti-Castro war—smuggling weapons to anti-Castro groups. It is all pretty damning stuff.

We all know this now, on the 53rd anniversary of the crime, but Hoover surely knew it then—and chose to conceal it. Its recent embarrassment may not be the FBI's finest hour, but it is a long way from its worst.

Image via

Us: Mr. President-elect, you have been elected for a week now. When are you going to build the wall?

President-elect: What wall?

Us: The wall to keep the "Mexican rapists" out.

President-elect: I never said anything about a wall. I never said Mexicans were rapists.

Us: You said it 3,000 times a day for the last year.

President-elect: WRONG.

Us: And what about getting all the illegal immigrants out of the country?

President-elect: I never said anything about immigrants. I want to bring people together. Didn’t you hear my acceptance speech?

Us: The one where you gushed over "crooked Hillary?"

President-elect: Why do you call that great American public servant crooked? I never said she was crooked.

Us: We got 1,000 messages a day from your campaign using that exact phrase.

President-elect: I was misquoted. I never said that.

Us: These were emails.

President-elect: I was mis-emailed.

Us: You also said the president wasn’t born in this country.

President-elect: WRONG. I have nothing but respect for the great job he has done. Didn’t you see my visit with him on television?

Us: And you didn’t say a word about him being a Muslim.

President-elect: I never said he was anything but a good Irish Catholic boy who got too much sun. Listen, you media people are all liars.

Us: That’s another thing. When you thought you were losing you called the media liars.

President-elect: WRONG. I never called anybody liars.

Us: You just did 10 seconds ago.

President-elect: No I didn’t. You media people are all liars. Except for the liars at Fox News. They are nice to me.

Us: And I guess you deny making fun of the disabled?

President-elect: I never did that. I would never mock a handicapped person. That was made up by the lying media.

Us: When are you going to revoke Obamacare?

President-elect: I never said I would. I would never take insurance away from 20 million poor people. You media liars don’t understand when you want to win, you say one thing, but when you win, you have to be president of all the people. I learned that from Hillary’s Wall Street speeches.

Us: Do you still think the election was rigged?

President-elect: Only if I lost. I have great respect for our institutions. America is great. I just hope I don’t screw it up.

Us: With all due respect, you don’t sound like the same man who ran for office.

President-elect: Well, as a matter of fact, I’m not. I’m the guy who played him on "Saturday Night Live." I’ve been hired to fool you morons in the media. There’s nothing like steady work. Trust me.

Image Via

Like all real Americans, we watch with interest those interviews with ordinary folk explaining why they are voting for whomever they favor. We take particular interest in those people who appear 30 or older who say they never voted before. Usually, they are for Trump. What does that tell you about their level of citizenship?

Actually, most people who say they are for Trump do not seem stupid. They may not have a college degree, but they speak pretty well and their concerns about the economy, foreign competition, etc. seem thoughtful. Nor do they seem like flaming racists. But you have to wonder why a number of those same people say they believe President Obama wasn’t born in this country, and that he is a Muslim.

We wish the interviewers in these situations would ask one more question. Where do these people get their information? Is it from Fox News, which has a well-earned reputation for a right wing GOP bias? And do they read a newspaper? We tend to doubt it, with newspaper circulation having dropped so precipitously. Even television evening news attracts far smaller audiences than in the days of Huntley-Brinkley and Walter Cronkite.

We wonder if these people are addicted to the internet, which is notoriously unreliable. Are these the kind of people who read that some American cities have adopted Sharia law, or that Target stores are owned by Muslims—and immediately forward that nonsense to all their friends?

You don’t have to be deplorable to do that. We have friends who are well-educated and highly successful, who don’t take the time to investigate such trash before they spread it on the internet.

It is ironic that the media are being savaged by Donald Trump at the same time that the traditional media have lost much of its influence? A test of that decline on a local level is coming up soon. Virtually every important newspaper in Florida has campaigned heavily against Amendment One on the ballot. It pretends to be supporting solar energy development, but in fact, is sponsored by the leading electric companies who want to control solar and prevent independent solar companies from enjoying the competitive benefits that they do in most states. It is a deceptive and shameful move, backed by $22 million in advertising.

The Sun-Sentinel and other South Florida papers have repeatedly and very visibly urged voters to vote against this amendment. Most recently, Sunday's Miami Herald had a major story (headline above), and Monday's Sun-Sentinel explained the disgraceful attempt to confuse voters. It is hard to believe that any voter who reads a major Florida newspaper regularly does not understand this deception by the power companies and will vote accordingly against the amendment. And yet newspaper readership has declined so much, and even though papers' digital versions are still widely read, there is a major difference in their formats. A newspaper can get attention with positioning and length of a story. That impact is largely lost on the internet.

Nov. 8 will be an interesting commentary on the state of the fourth estate in our state.

Headline from Miami Herald

Win or lose, Donald Trump has done the public a service by being probably the first candidate for the presidency, and perhaps any high office, to openly admit that bribery is good. He has boasted in his crude way that he gives liberally to candidates in order to buy influence. And circumstances in Florida pretty much proved it when it was revealed that his foundation donated $25,000 to Florida Attorney General Pam Bondi, shortly before she declined to join a lawsuit brought against Trump University for defrauding students in Florida.

Trump can acknowledge his fondness for bribery because, under current campaign contribution rules, bribery is not a crime. It’s only a crime if you get caught on a recording saying, “I’ll accept your campaign contribution with the understanding that I’ll vote for anything you want me to.” Quid pro quo.

That doesn’t happen very often. But it apparently happened in Pennsylvania, where a former state treasurer and a massive campaign contributor were recently indicted. The treasurer was taking campaign contributions in return for allowing a financial company to be a “finder” for money managers to handle state funds. The finder contributed $3 million but got back several million a year from the favored findees. The details have not come out, but the papers reported that an undercover federal informant and tape recordings were involved. We discussed this case in the current issues of several of Gulfstream Media Group’s magazines. We wonder why, if they aren’t already doing it, the feds aren’t looking at the history of massive campaign contributions by Big Sugar (major sugar producers and related agricultural interests), which have had such a detrimental effect on the Everglades and major waterways on both sides of the state.

All bribery of public officials costs the taxpayers eventually, if only in the legal tab to put them in jail, but the situation in Pennsylvania, in which parties simply enriched themselves, seems petty compared to Florida, where tourism and water-related businesses on both side of the state are damaged, the Everglades are endangered and, eventually, the water supply of all South Florida may be threatened.

The campaign contributions ($8.5 million by one sugar company) ensure that no matter how loud the public outcry, the votes to buy the land south of Lake Okeechobee necessary to restore the natural flow of water south into the Glades never seem to be there. Even legislators who live in areas most severely damaged usually vote for Big Sugar over their own neighbors. Those same legislators usually win handily. Why? $8.5 million has a lot to do with it.

Joan E. Friedenberg of Boynton Beach, in a letter to The Palm Beach Post earlier this summer, supplies some details. Martin County (Stuart, Fort Pierce) has been most damaged by the disastrous algae blooms (seen above on a Treasure Coast waterway) caused by polluted water being pumped into the salt-water estuary in Stuart. Businesses and residents have been screaming, but reader Friedenberg points out that they don’t take their anger to the ballot box.

She points out that Gov. Rick Scott, accused of ties to Big Sugar, beat environmentally friendly Charlie Crist by 55 to 40 percent in Martin County. Pam Bondi, Scott’s lackey, won by 66 percent to 31 percent. Two influential state elected officials seen as friendly to sugar interests won with 63 percent and 74 percent support. Go figure. Can Martin County voters be so uninformed, or does $8.5 million set the political agenda?

Until the feds get involved, or Martin County voters wake up, let them eat algae.

Photo provided by Ecosphere.

It was the early 1970s. We were new in town, still trying to figure out which way the ocean was, but we had learned that Maggie Walker was a reliable source. She was assistant editor of Gold Coast magazine, and when she suggested a piece on a fellow who had a renewal plan for Fort Lauderdale’s downtown, we trusted her judgment.

It was the early 1970s. We were new in town, still trying to figure out which way the ocean was, but we had learned that Maggie Walker was a reliable source. She was assistant editor of Gold Coast magazine, and when she suggested a piece on a fellow who had a renewal plan for Fort Lauderdale’s downtown, we trusted her judgment.

Thus we learned about Stan Smoker, who had come to town in the 1950s, leaving behind a family business in Indiana. He took a job driving a truck for $40 a week, and went on to become a developer who saw the future of downtown Fort Lauderdale when the tallest building was about five stories high and Las Olas Boulevard was filled with gray windows of vacant stores. At the time, Commercial Boulevard, several miles to the north, was the center of entertainment.

The article included a double page rendering by the architectural firm of Gamble & Gilroy. It seemed absurdly optimistic, showing new tall office buildings and condos and featuring a new library and art museum. All expected to happen within a few years. It did not happen—not then. The economy took a downtown, and the city’s major department store, Burdines, even moved out to the new Galleria Mall. It was a time when Bill Farkas, the new downtown development director, built tennis courts to give the appearance that something was happening where old buildings had been razed.

Stan Smoker never lost faith in his concept, however. He had acquired land on both sides of the New River and on Las Olas, and eventually, his vision rose from the ground. He died this week, at age 94, having lived long enough to see his concept fulfilled even beyond his ambitious plan, and having his foresight memorialized in Smoker Park, along the south side of the New River, part of his original holdings.

Smoker’s optimism was his style. His son Ed, now a developer, told the Sun Sentinel his father wanted people to like him. They sure did, and he made friendship seem easy, with a happy personality that made you feel like the most important person in the world. Until the last year, when his health declined, he remained highly visible and little changed from the enthusiastic fellow of the 1970s.

Nowhere was that energy more apparent than when, a few years later, Maggie Walker again brought his name up in connection with his plan for developing Scotland Cay in the Bahamas. She went over to cover the story, along with photographer Bob Ruff. Her piece made it sound like a great place for a second home, free from commercial overkill. It featured a shot of Stan relaxing at one of the few homes on the island. You can feel his exuberance in the photo.

Again, his instincts were correct. Not only did he attract prominent Gold Coast people to invest in the island, he also sold to Europeans. Years later he credited the magazine for helping him put Scotland Cay on the map. It probably would have worked as well without the publicity, but appreciation was part of Stan Smoker’s engaging way.

For this Gold Coast pioneer, optimism was its own reward.

He had a pretty good job for a young guy. Roger Ailes was the producer of the popular "The Mike Douglas Show," at the time based in Philadelphia and a pioneer in the field of daytime TV talk shows. But the 28-year-old Ailes had not had a national reputation until he suddenly became the star of a best-selling book. Joe McGinniss, also in Philly at the time, had quit his job as the young featured columnist for the Philadelphia Inquirer to follow the campaign of Richard Nixon in the 1968 presidential race.

McGinniss was a liberal, but somehow he conned his way into Nixon's campaign, to which Ailes was the media adviser. Ailes had met Nixon through the Douglas show and bluntly told the future president that he did not understand the power of TV. Impressed, Nixon hired him. Joe McGinniss and Ailes hit it off, and the writer got a remarkable behind-the-scenes look at a very contrived made-for-TV campaign. A big part of the story was Ailes, who concealed nothing from the writer, including his often irreverent and highly amusing comments about his own candidate, and his cynical contempt for the intelligence of the American voter. Ailes designed a campaign in which Nixon avoided the legitimate press; instead, he appeared at mock town hall meetings filled with hand-picked supporters who asked questions which, while ostensibly sincere, were crafted for Nixon's prepared answers.

It all came out in the blockbuster book, "The Selling of a President – 1968," which made both McGinniss and Ailes familiar names, at least in political circles. The praise it earned Ailes as a political operator also hardened his conviction that news could be manipulated to present political propaganda as legitimate reporting. It was not a novel concept. The Nazis were pretty good at it decades earlier, but that was before TV. We know that McGinniss/Ailes story well. We wrote about both men during our days at Philadelphia magazine.

Ailes always seemed to have had a right wing bias; he thought liberals dominated the media, but for years, he was a hired gun. He worked a time for NBC and gave the ardently liberal Chris Matthews his first shot. But mostly, he consulted for Republicans, with notable success. He earned professional respect for helping Ronald Reagan conceal his growing senility and provided the grossly unfair racist ads, which propelled the first President Bush to the White House. But it was not until 1996, when he launched Fox News with Rupert Murdock's money, that his idea of a news organization devoted to conservative, mostly Republican values, became reality.

Twenty years later his success is obvious. Fox News is a leader in the news field. Until he recently got ousted for sexual harassment, Ailes made money Donald Trump would admire.

Roger Ailes’ concept has fulfilled his ambition of countering the liberal media bias with a "fair and balanced" network. He launched a corrupt propaganda machine with that patently dishonest slogan. To the surprise of almost all serious journalists, it worked. We wonder today how much 20 years of daily news distortion has molded U.S. public opinion to the extent that a Donald Trump, with all his crudeness, prejudice and ignorance of foreign affairs, can seduce such a large portion of the electorate.

Polls show he is most popular with white men without a college education. We feel certain most of that group are those who have given up newspapers, if they ever read them, and probably have little use for conventional NBC, CBS and ABC newscasts. But what surprises us is how many of our intelligent, college-educated friends also seem to prefer Fox's fair and balanced distortions of any story with political implications to the traditional news format established by such TV news icons as Edward R. Murrow, Huntley-Brinkley, Walter Cronkite and Eric Sevareid.

Die-hard Fox fans will point to MSNBC as the left-wing equivalent of Fox's right-wing filter. But there are differences. MSNBC does not deny its bias toward progressive opinion; it actually promotes it. But it also draws on NBC mainstream stars, such as Tom Brokaw and Brian Williams, to achieve a degree of balance. This week’s repeated harsh criticism by "Morning Joe" Scarborough about Hillary Clinton's (rare) Sunday interview on Fox regarding her email controversy is the kind of reverse form candor you rarely see on Fox.

Fox does present alternate views. It discovered that people fighting on camera pull better than undiluted propaganda. It also may be tired of being the butt of jokes by the real people in our business.

This rant appears after two weeks vacation in the North Carolina mountains, watching Fox every day, switching back and forth to other news channels for comparison. Some political stories are covered much alike, but the most important ones take on the Roger Ailes slant. One that stands out is the repeated economic refrain—the country is going to hell, and we need change. Growth is slow, wages stagnant. When people hear that day after day, they tend to start feeling sorry for themselves.

Fox does not mention that when President Obama took office, things were really scary. The stock market had collapsed. Sales signs dominated neighborhood lawns. The auto industry was in peril. Our magazine company sales dropped a full third in a matter of months. Executive salaries went down about as much. Now, friends, that was real trouble in River City.

Today, unemployment is low. The stock market is at record levels. Warren Buffett, who is entitled to an opinion, says things are pretty good. You may even hear some of that on Fox, but you have to listen fast. It won't last long.

Image via

The big story in Sunday's Philadelphia Inquirer struck close to home, even from 1,300 miles away. Two financial guys are under investigation for enormous campaign contributions to various Treasurers of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania who control billions of dollars of state money to be invested with whatever investment firms the treasurer deems fit. In this case, the state treasurer saw fit to turn that money over to firms recommended by the two financial guys who had just sent $150,000 each (on the same day) to the treasurer's campaign chest. Before that treasurer left office, she received $475,000 in contributions from the two financiers.

This was back in 2000, but it was just the beginning of a pattern that went on for more than a decade involving various public officials. The financial guys are described as "finders," and their political contributions amounted to around $3 million over the years. The fees they received from the money managers who got contracts amounted to many millions more over the years, enabling the two men to enjoy satisfying lifestyles. We will not name the two financial guys; they have not been charged, and one of them is from our alma mater, which has never produced anything but saintly figures—unless you count a few sons of Mafiosos. The Inky (local parlance) revealed that an official already convicted has been wearing a wire for the feds for two years, taping conversations with one of the financial guys. If you are that guy, you really don't like to read that in the paper.

It is all part of a federal "pay to play" probe in Pennsylvania, which has earned a rep as one of the leading states for that kind of corruption. Florida was not ranked in that category, but given the climate of the last few years, we surely deserve consideration.

It appears that the feds are looking at the possibility of political contributions being considered criminal bribes. That should be welcome news on the Treasure Coast, where a movement is underway to have the authorities look into the massive contributions from Big Sugar, which have increasingly controlled state government and particularly influenced local legislators who ignore the people who elected them, with disastrous results for the environment.

The important difference between the contributions in Pennsylvania and those in Florida is their impact on the state. Pennsylvania involves facets of government most people never think of—and are hardly affected by the legal bribery. In Florida, the contributions have produced environmental damage, which directly affects thousands of people, seriously damaging the economy of beautiful counties on both sides of the state and creating a health hazard for those who live and work there. Compared to Florida, the Pennsylvania corruption seems almost trivial.

Our guess is that given the recent and totally predictable consequences of discharges from Lake Okeechobee, which the disaster named Gov. Rick Scott blames on the federal government rather than his own political hacks who have caused it, the feds have to take notice. Political corruption in Florida is worse than Pennsylvania. And if the feds are not on this case already, they should be.

Image via